“A Silk Road Oasis” is the British Library’s most recent, perhaps most creatively themed exhibit on Dunhuang to date. Running from 27 September 2024–23 February 2025, its core offering is a showcasing of a large and diverse collection of exquisite manuscripts centered around eight archetypal characters that would have lived in Dunhuang. These characters are part of the nine sections of the exhibit:

“The Cave” (in reference to Cave 17, or the Library Cave),

“The Merchant”

“The Diplomat”

“The Fortune-teller”

“The Lay Buddhist”

“The Buddhist Nun”

“The Scribe”

“The Printer,” and:

“The Artist”

Accompanying the exhibit is an excellent book by the curator, Mélodie Doumy. A Silk Road Oasis the book is not as simple as a catalogue; which the contents page makes clear. It sets the broader “stage” of Dunhuang on which the lives of our eight archetypal characters are acted out. Mélodie provides the context in which Dunhuang became important:

Dunhuang, in present-day Gansu Province, north-west China, lies in an oasis between the Gobi and Taklamakan deserts, nestled amid the Kunlun and Tianshan mountain ranges. . . . This strategic location made it one of the ancient world’s most important junctions between the East and the West, an almost mandatory passageway for Silk Road travellers. . . . The original town was founded in 111 BCE bas a military outpost to protect the territory then ruled by the Chinese Han Empire (206 BCE – 220 CE) against the invasion of nomadic tribes, especially the Huns, and to help conquer lands further west.” (8)

Mélodie goes on to explain how the town became a prosperous, multicultural conduit for commodities, knowledge, and people, and how the acclaimed Mogao Caves, a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1987, came to be. Her first chapter proper, “Cave 17,” opens with the end of the overland silk routes as Eurasia’s primary economic and cultural veins of trade, prosperity, and cultural exchange. Dunhuang’s loss of commercial and strategic importance meant that the town slipped into decline, and the Mogao Caves became derelict and filled with sand over the generations leading up to the 19th century.

The accidental discovery of the so-called Library Cave by self-appointed guardian, Wang Yuanlu, was one of the most momentous uncoverings for China and the world. Mélodie also describes, in neutral and impartial language, the process of how Wang Yuanlu eventually sold “a large portion of the repository’s contents” to Aurel Stein. (26–28) However flawed Wang’s sale was, it was clear that he sold the manuscripts to fund the preservation of the Mogao Caves. The chapter concludes with how the imperative to protect the caves led to the formation of organizations like the International Dunhuang Programme, of which Mélodie is part.

The next three chapters, “Civic Life,” “Religious Life,” and “Creative Life” highlight some of the stories of the character archetypes of the exhibit. Throughout the book, Mélodie provides images of the manuscripts related to these themes of life. One item she highlights is the letter of the Sogdian merchant’s abandoned wife, Miwnay, who is in a terrible situation:

Miwnay moved from Samarkand to Dunhuang with her merchant husband, Nanai-dhat. This letter, found in a lost mailbag, was written by Miwnay to her husband. Having not heard from him in three years, Miwnay and her daughter Shayn have become destitute and are forced to serve a local Chinese household. They are desperately trying to leave Dunhuang but to no avail. Was the family ever reunited? Did Nanai-dhat perish on the dangerous Silk Roads? (36)

The letter provides not only a rare glimpse into the intensely personal concerns and problems of a Sogdian individual, but also serves to remind us that these people’s lives were not something abstract, but as real as our very own lives and those of our loved ones.

Divination, astronomical, religious, tantric, and medicinal texts in multiple languages, from Uyghur to Tibetan to Chinese: Dunhuang was a socio-political and cultural medley of vibrant threads. I am particularly impressed by the attention Mélodie devotes to lay Buddhists, who:

. . . were instrumental in sustaining and propagating Buddhism. Whether they hailed from other places or were established members of the local community, they supported monastic institutions through donations, sponsored the construction of temples and of caves at Mogao and commissioned the production of Buddhist manuscripts, prints and artefacts. In the fifth century, following the lead of the Chinese imperial court, both powerful families and ordinary members of society embraced Buddhism. Merchants, diplomats, officials and members of the ruling elite all engaged in acts of patronage as a means of accruing merit and ensuring a favourable rebirth in the next life, whether for themselves or for relatives. (61–62)

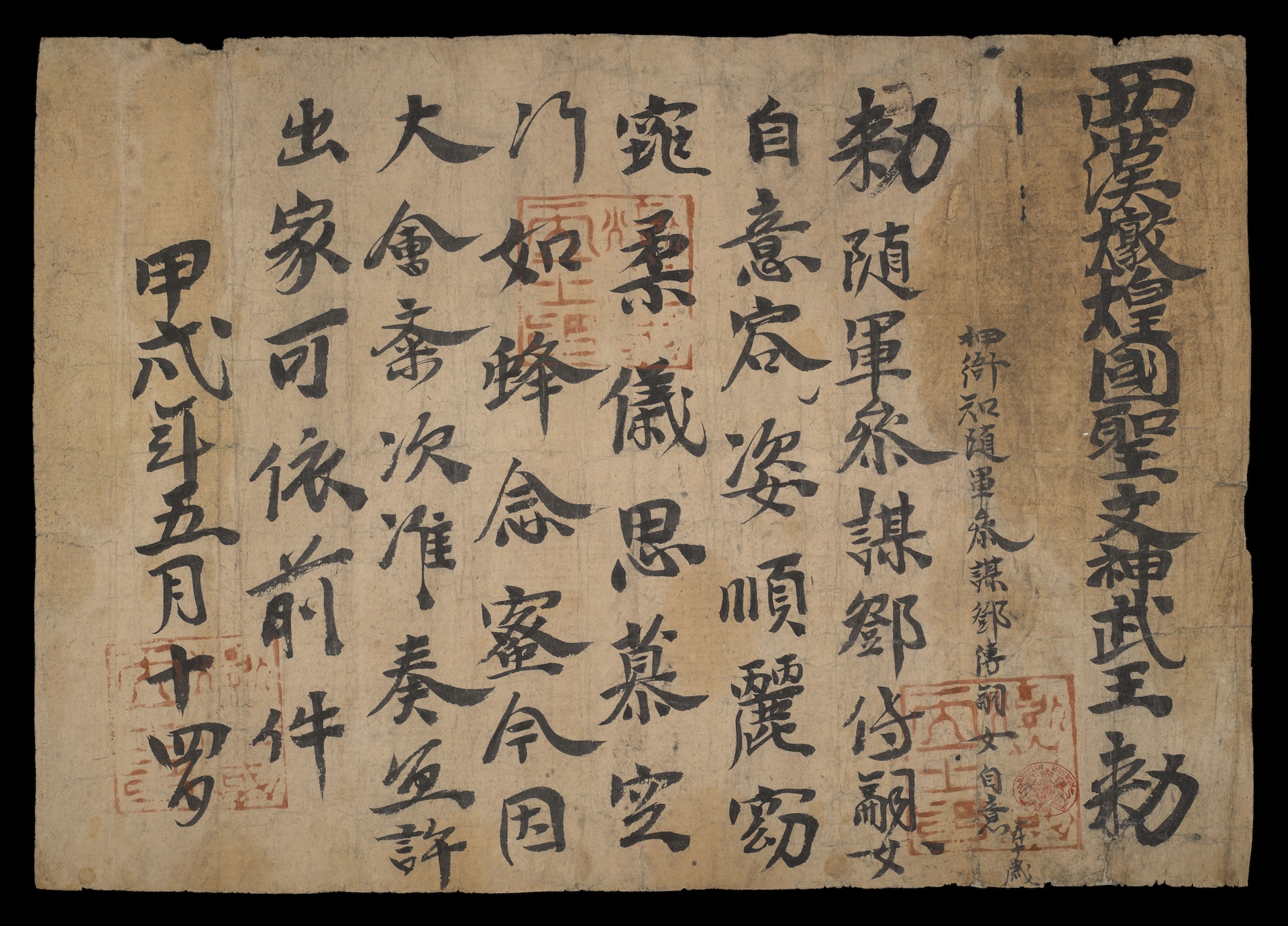

Another fascinating segment of “Religious Life” is the part about Buddhist nuns, who numbered more than monks at Dunhuang between the years of 800–1000. This extraordinary fact, along with how we have clear records like those of Dacheng Temple (one of the five nunneries at Dunhuang) and its 209 female members, should give impetus to double research efforts into these extraordinary lives. One of them was the female novice Deng Ziyi, whose ordination certificate is preserved and on display too. As Mélodie writes:

Despite a prohibition on joining the clergy before the age of twelve, enforcement was lax. In ninth- and tenth-century Dunhuang, individuals were required to obtain official approval from the government to pursue monastic life as a nun or monk. The ten-year-old Ziyi received this permit dated 914, exceptionally granting her permission to become a novice. The document bears the ‘Seal of the Celestial King of Dunhuang’, Zhang Chenfeng, three times.

‘Decree: As ensues, the daughter of the Military Officer Deng Chuan, Ziyi, of smooth appearance and gentle poise, whose longing for Buddhism is like the yearning of a bee for honey, at this time of Grand Food Offering Ceremony and in accordance with this petition, is authorised to enter a nunnery.’ (77)

There are many more stories to mention, but there is no better experience than to read the volume itself. The book is not only an excellent complement to this milestone exhibit. It distills the vast and ambitious story of the exhibit “A Silk Road Oasis” for readers, much like the concentrated elixir of a fragrance. It is storytelling at its most historically informed and academically refined, yet remaining human and at many parts, moving.

Stay tuned for Mélodie Doumy’s upcoming interview with us in November

Reference

Mélodie Doumy. A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang. 2024. London: The British Library.

Related features from BDG

Buddhistdoor View: Telling a history we can all resonate with through Dunhuang

Related blog posts from BDG