Why do we tell stories? Throughout history, the storyteller was the sage, the wise one. Stories have a mythic, primeval place in human society and culture. They are expressions of our deepest intuitions, our oldest folk memories, and our sense of ultimate destiny. At a social level, they speak to our times and advise us on how we think about the world, relate to others, and live our lives. Throughout history, stories have been especially important during times of crisis: political upheaval, famine, mass migration, and in this difficult time, pandemics.

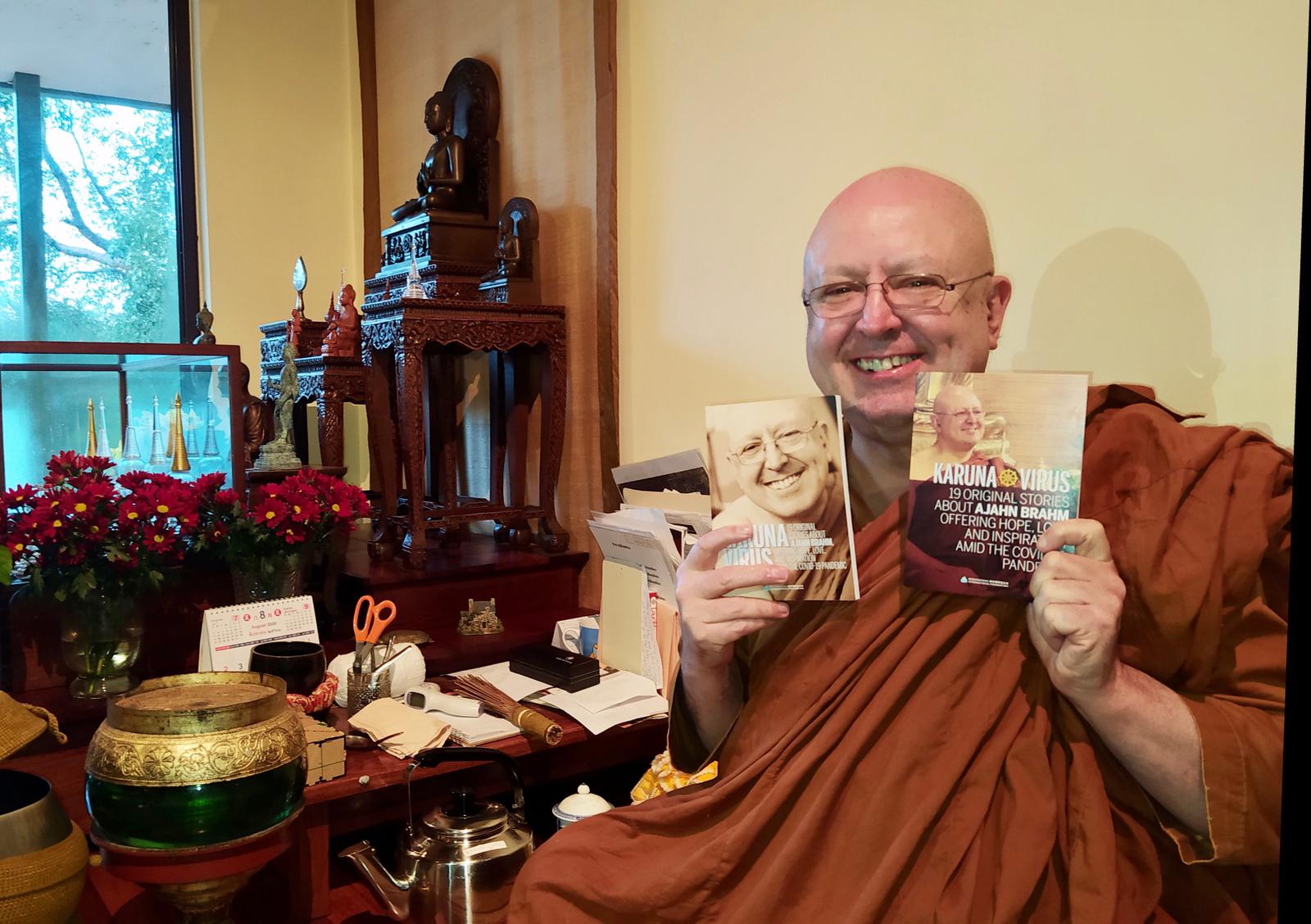

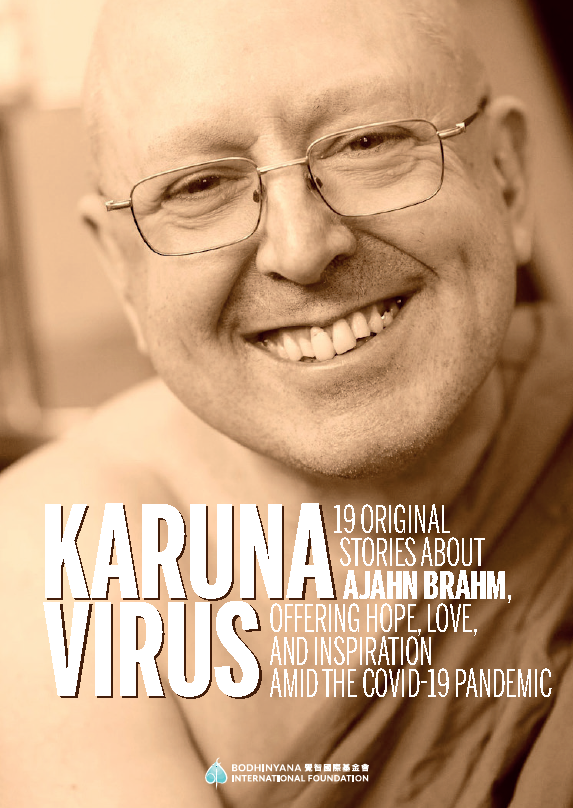

How fitting, then, that in this historic and difficult global period – the age of COVID-19 – the Bodhinyana Foundation has released a compilation of stories featuring Buddhist monk Ajahn Brahm, called Karuna-virus: 19 Original Stories about Ajahn Brahm, Offering Hope, Love, and Inspiration Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. This title is a wordplay that substitutes “corona” with karuna, the Pali and Sanskrit word for compassion. And wouldn’t we rather have a pandemic of compassion and caring rather than COVID-19?

As the introduction says: “Inspired by Ajahn Brahm’s timeless teachings, the aim of this book is twofold: first, to use 19 never-before-published stories from Ajahn Brahm’s life to bring joy and give hope to anyone whose life has been affected by COVID-19; and second, to present it as a gift to Ajahn Brahm on his 69th birthday, on 7 August 2020.” These stories were drawn from retellings by Ajahn Brahm’s senior monastic disciple, Ajahn Brahmali.

So many have had their lives adversely affected by COVID-19: fear and powerlessness faced by all in the face of this invisible foe, real losses and deaths (particularly among the elderly or sick), jobs lost or savings diminished, businesses shuttered, and an entire generation of youth staring at a much more unpredictable, unstable world. Yet the forced adaptation of societies and economies to the post-COVID-19 world have prompted some genuinely good trends: a re-prioritizing and rethinking of what’s truly important, a serious look at society’s flaws and fragilities, and an intensified search for meaning beyond wealth, success, or even “stability.” Authentic Buddhism cuts to the chase, presenting us with the ultimate insecurity: no-self, anatta. Ajahn Brahm teaches this doctrine through his characteristic humour and relatability in the stories gathered here.

There are nineteen (the number purposefully chosen to allude to COVID-19) stories in this beautiful anthology. I have several favourites. Each story is only about several paragraphs long, taking up no more than one or two pages. The only exception is the final chapter of the book, which is titled, “The Life of Ajahn Brahm: An Unauthorised Hagiography.” (pp. 51- 73) Each story highlights Ajahn Brahm’s beloved qualities: wisdom and kindness shine through the pages, but so do humour, rebelliousness, and independent thinking. Ajahn Brahm is famous for being among the most straight-talking monks of the Theravada tradition, even among his Australian Theravada counterparts (among whom many are already more direct in their pedagogical style than their preceptors).

I am particularly fond of “Batty About Caves” (pp. 36- 37), which describes the Thai caves that Ajahn Brahm practiced in as “natural cathedrals to meditation.” So accustomed that he’d become to the ambience and environment of these caves that when he returned to Australia many years ago, he considered (but dropped the idea) of importing bat droppings from the Thai caves. As is common in Ajahn Brahm’s tales, what we assume to be bad things or unpleasant situations are simply not so if we can adopt a more open perspective. As it happens, bats are endemic to Australia, and are stereotypically seen as frightening creatures of the night (think of Batman, or even the theories about the origin of COVID-19). Yet far from their forbidding image in vampire novels and pop culture, they are actually very cute and friendly, nicknamed the “doggos (dogs) of the sky.”

Another wonderful story is “A Bear Hug for a Beggar” (21 – 22), which recalls yet another occasion where Ajahn Brahm simply thinks differently from many others, and as a result, is able to show people the deeper layers of life, rather than simply looking at superficial appearances or buying into cheap assumptions. The very first story of the book, “The Bushfire” (14 – 16), is also very poignant, encouraging us to persevere in works of meaning and importance to us, even if it comes crashing down one day and we must rebuild from scratch. Although the Australian bushfire that was feared would burn down Ajahn Brahm’s monastery happened in 1991 (eventually it did not), there is a thematic parallel between then and last year’s Black Summer, during which 18.6 million hectares (46 million acres) were burned and 34 people killed, and just as tragically, an estimated three billion non-human brothers and sisters. Ajahn Brahm rebuilt his monastic home with courage and compassion in 1991, Australians in the outback are rebuilding their lives and razed homes even now, and when the global pandemic truly recedes, we will all need to come together to rebuild as well.

From fresh perspectives to rebuilding from the ruins, Karuna-virus manages to be accessible while delivering multilayered themes deserving extended reflection. This is an anthology for anyone seeking some refuge from the storm. This is a heartwarming and inspiring book that will provide many nuggets of wisdom and food for thought for its readers. Do not underestimate the power of stories. Stories can change our perspective, strengthen our better angels, help us make peace with reality, and comfort us during difficult times. Karuna-virus is one such example of the power of stories and the spirit of embracing what tries and tests us.