What symbols do we recognize most in our corporatized world today?

Logos like those of the apple of Apple Inc. or the arched M of McDonald’s? What about images as innocuous as the male and female figures on restroom doors, ingraining in us specific assumptions about reality and directing us to live our lives in the way that conforms to the way society has been structured?

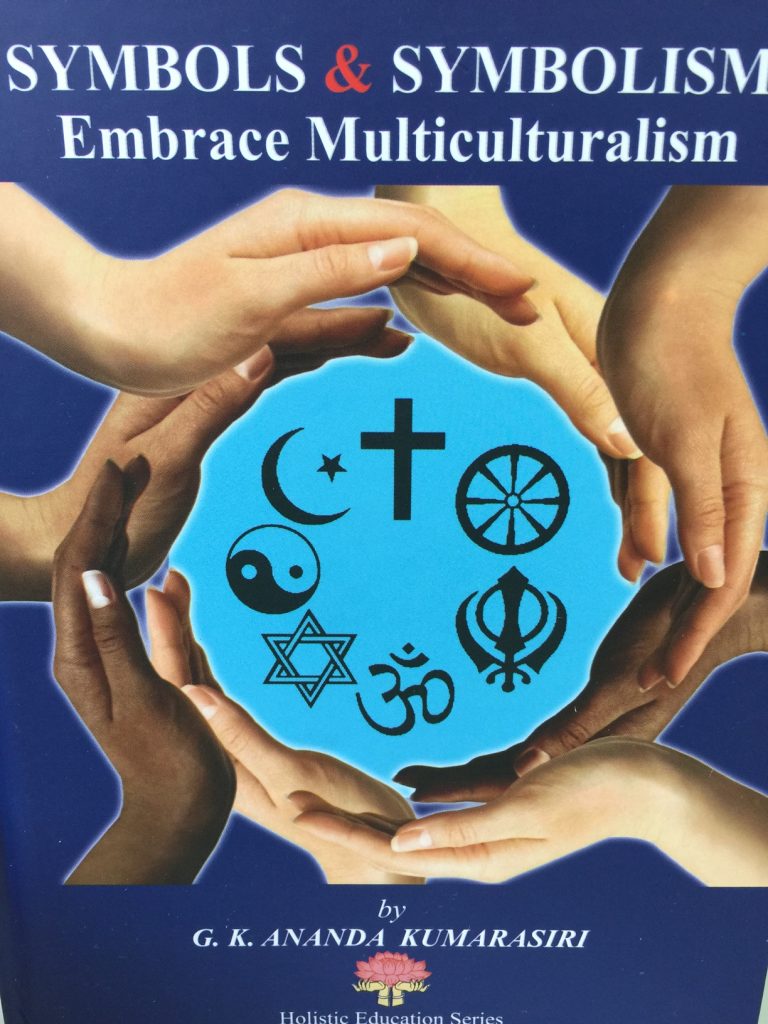

What a terrible pity, then, that religious symbols have been relegated to the periphery of modern life. Unless one is immersed in a religious lifestyle as an active churchgoer or involved in religious charities on the weekends, there is a secular aversion to even seeing the multitude of transcendent motifs of humanity’s spiritual inheritance in public. This is the paradigm that my good friend Dr. Ananda Kumaraseri wishes to challenge in his new book, Symbols & Symbolism: Embrace Multiculturalism. As long as symbols are deployed wisely (and they are abused all the time to whip up greed, hatred, and delusion today), symbols can “steer societies along a wholesome path when used with right understanding and wise application.” (49)

Dr. Kumaraseri is a prolific writer and speaker on traditional Buddhist values. He is president of the Human Development and Peace Foundation and a retired Malaysian diplomat. He has served in diverse capacities like counselor in New Delhi from 1972–75, counselor in Tokyo from 1975–78, minister in Washington, D.C. from 1981–84, and ASEAN’s director general from 1993–95. Today, he is one of the permanent representatives of the World Fellowship of Buddhists to UNESCO.

Dr. Kumaraseri is a prolific writer and speaker on traditional Buddhist values. He is president of the Human Development and Peace Foundation and a retired Malaysian diplomat. He has served in diverse capacities like counselor in New Delhi from 1972–75, counselor in Tokyo from 1975–78, minister in Washington, D.C. from 1981–84, and ASEAN’s director general from 1993–95. Today, he is one of the permanent representatives of the World Fellowship of Buddhists to UNESCO.

Last year I had the pleasure of getting a sneak peek into a project Bro. Kumaraseri has poured a great deal of love and effort into: the ongoing and gradual transformation of consciousness and re-orientation of priorities in global society. This book is primarily a Dharma book, a work devoted to the Buddhist perspective on symbols of Dharma: the lotus, the wheel, the bodhi, the stupa, and the contemporary Buddhist flag that was adopted by the world’s Buddhist community in 1952, at the World Fellowship of Buddhists, as a generic indicator of spiritual belief and affiliation. Dr. Kumaraseri speaks eloquently about the need for society to rediscover the benefits of a mass awareness about these symbols (particularly in Asian Buddhist societies, which have recently been overtaken by a frenzy of materialism and indifference to religion), but also about how the young need to be educated in the ways symbols can be abused. After all, the Nazis had symbols too: the most sinister among them being a perversion of the Indic swastika.

Dr. Kumaraseri’s call to awareness is both urgent yet optimistic. We need to get back in touch with the history of the symbols that permeated our traditional societies, and bring them back to prominence in a healthy and productive manner: for example, the Wheel of Dharma, or dharmachakra, is the prime symbol of institutional Buddhist religion (my father gave me an elegant lapel pin depicting the Dharma Wheel, which I wear on one of my coats). It not only points to the spiritual awakening of the Buddha and the path he prescribed for all beings, but also invokes the chakravartin, or wise ruler, which in this age of disillusionment with politics we sorely need across the world, in every nation. “His reign accordingly is characterised by high moral and ethical standards. This includes sustainable development and deliberate policies and measures aimed at safeguarding the ecology and all living beings, including animals, other creatures and nature.” (157) Asian political leaders throughout the millennia, from emperors to kings to presidents and prime ministers, have invoked the chakravartin. But how deeply have they truly absorbed the values and spiritual message of the Dharma Wheel?

I think in this volatile age, we must make a real effort to retrieve the archetypal forces that gave generations of humanity, across thousands of years, existential weal and purpose. Dr. Kumaraseri argues boldly for a grand vision, to be taken on by all segments of society, including government, education, and religious institutions, to “encourage among their individual communities a right understanding and appreciation of symbols and symbolism.” (50) Bro. Kumaraseri has written a passionate and eloquent book that I heartily recommend to every Buddhist community and anyone who wishes to learn more about the power of our non-corporate, spiritual, primeval archetypes.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Straight Talk: Reforming Buddhist Education in Asia, with Dr. Ananda Kumaraseri