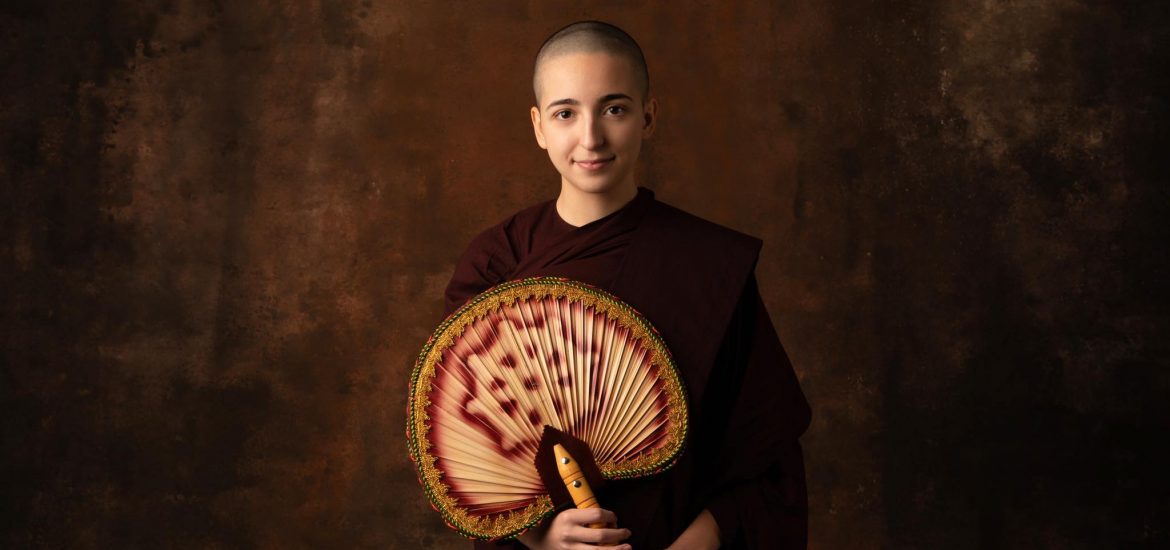

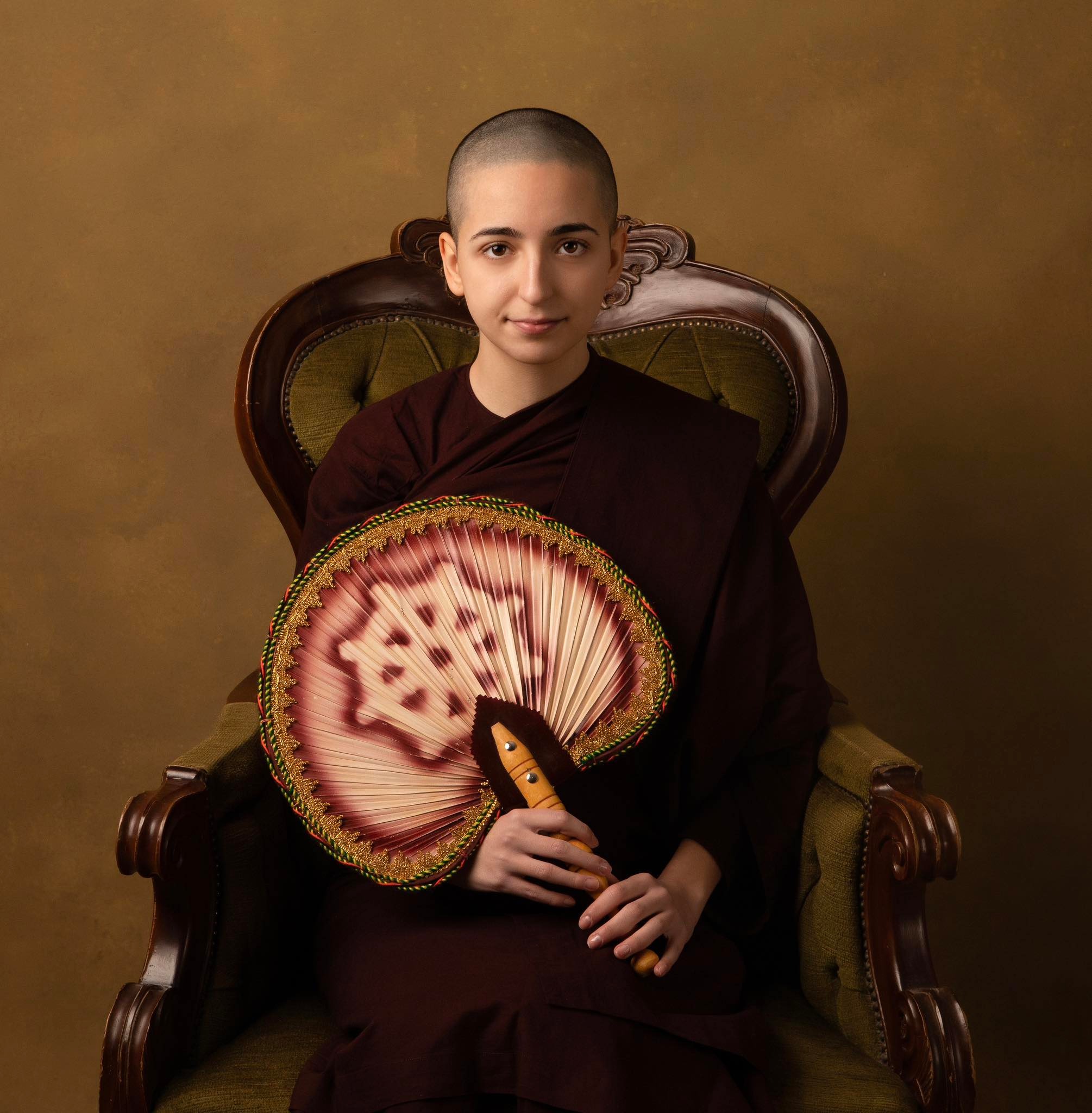

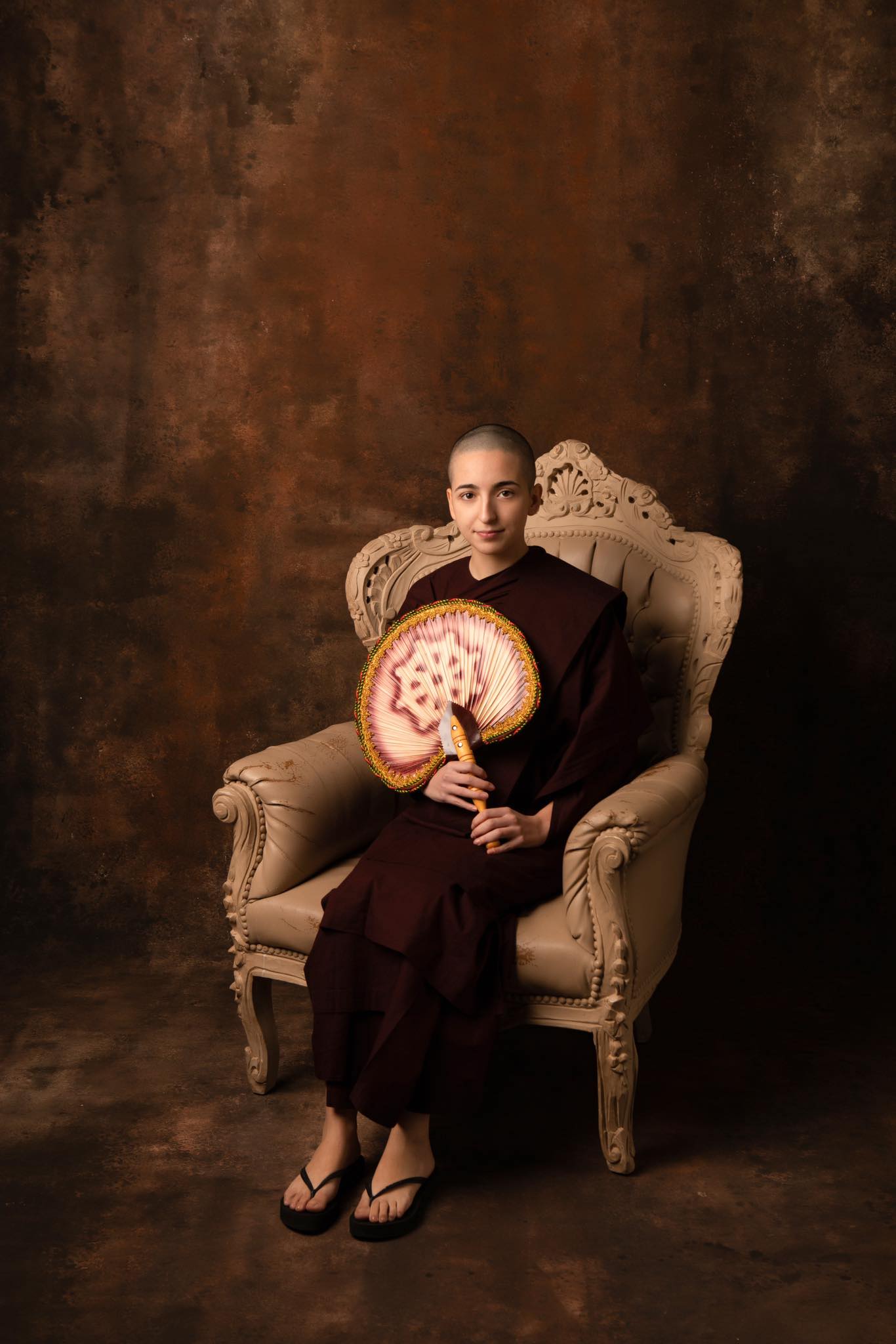

Gotami Yadanar has been travelling through Myanmar this March. It was a joy to see, from photos she sent me, glimpses of her voyage, such as riding in a car with friends on a busy road, or encountering Burmese monastics and laypeople. In fact, the Italian-born thilashin (female renunciant within the Burmese monastic tradition) had come to Myanmar for a purpose that was personally important to her. She was overjoyed to finally meet and donate to a fellow female monastic who she calls her “heroine.”

This monastic is Sayalay Khemaranthi, who runs a monastery with as much discipline, rigor, and activity as any monk. Incredibly active, driven, and constantly on the move, Sayalay Khemaranthi has earned a large and loyal following that respects her, in effect, as a fully ordained teacher (even though thilashin are not for ordained bhikkhunis and there is no legal mechanism to become one in Myanmar).

“I never thought this day would come. It is like a dream come true,” Gotami shared in a post with photos on her Facebook page. “She [Sayalay Khemaranthi] runs her monastery with dedication, knowledge, and compassion.” While Gotami might urge me to not compare her to her star, I truly believe that she and Sayalay Khemaranthi share many things in common. They are both young women who have chosen to live as members of the “community of sanctity” (the sangha) in the Burmese tradition, with all its potential and limitations. They also happen to be active on social media and run wildly successful and lively Facebook pages, on which they enjoy large numbers of followers. Their youth, personal and online charisma, and personal convictions are not isolated qualities; they are in fact interconnected and form a unique conventional identity shared by the two women.

Earlier this year in February, Gotami met with the Italian Buddhist Union (UBI), discussing with its members the various problems and issues of Theravada Buddhism in Italy. Despite the collegial and informal atmosphere, the weighty matters included topics like Buddhism’s diffusion and propagation in a traditionally Catholic society, how to help Buddhist centers in Italy flourish, and how to help foreign religions integrate into communities with established social and cultural habits and sensibilities. It is inspiring to see the diverse worlds that Gotami can step in and out of, from a traditional Buddhist society like Myanmar to one that is still absorbing it. It is also encouraging to glimpse how Gotami attracts listeners and helpers along her (admittedly fresh) journey. When I speak with her about her Dhammadhuta work, I suspect that something similar to Sayalay Khemaranthi is at work: people see her less as a thilashin and more as an outright teacher, someone who reminds Buddhists the seriousness and power that can be held by a monastic with the right motivation and means (upaya).

Gotami herself takes pains to remind people that: “Where you come from” and your present status “doesn’t make you less or more able to understand the Dhamma. Whoever is willing to study the scriptures and try to keep the teachings alive, is a Buddhist. The one who has the intention to keep at least the Five Precepts as much as she or he can, is a Buddhist, a virtuous one. That’s all. Use our diversity and collage of rich experiences to connect with each other, not to distinguish or tear us apart. Especially when it comes to religion.”

This idea can easily be extended to gender; and while there is no denying that her presence is all the more striking because of the paucity of female teachers, it takes little imagination to envision how much more revitalized and expansive the diffusion of contemporary Buddhism could be if there were a greater share (which would mean many more resources put into training and nurturing) of female teachers.

In a post to her followers on her Facebook page, Gotami wrote: “According to Buddhism, a ‘Buddhist’ is someone who has taken refuge in Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha and believes in the Buddha-dhamma. On the plane of ultimate reality, there is no ‘this or that country/continent/planet Buddhist.’” Perhaps herein lies the secret of her charisma and conviction, which radiates from her being and touches all she meets. She lets people coming into contact with her see and feel for themselves that there is no need to single out her conventional status as a “Burmese Buddhist,” a thilashin, or a biologically female individual. There is, in fact, no need to single out anyone’s conventional status (except when addressing systematic injustices, I would argue). Ultimately, what distinguishes a good preacher of the Dhamma is their ability to draw people into the riches of the Three Treasures, planting the seeds for potential refuge taking sometime in the future. The inspirational power of members of the “community of sanctity” is real. This sense should be taken seriously and recaptured, and practitioners like Gotami are helping many to remember this sense of reverence and excitement.

Charisma and moral power are important factors in Buddhist life in Myanmar. Although focused only on monks, a 2009 study by Hiroko Kawanami examined the various Burmese terms and discourse deployed to indicate the sources of spiritual authority and charisma tapped into by male monastics. There is a Burmese word, àwza, that is defined as “a kind of reverential authority that makes people spontaneously want to offer their services, but without any form of coercion.” (Kawanami 2009, 223) It remains to be seen if a word like àwza will ever be applied to female monastics, be they bhikkhunis or thilashin. But with this new generation of thilashin that are breaking past old boundaries, finding global audiences online, and sometimes even outside of local ecclesiastic structures and therefore free from potential censure or pressure, such a conversation seems almost inevitable, or is on the cusp of beginning.

Despite their restrictions, thilashin still are given the honorific of sayalay, “little teacher.” As a holy woman by the standards of any spiritual tradition, Sayalay Gotami is profoundly animated by her immersion in the Four Noble Truths and transcending suffering through the Noble Eightfold Path. Like many other thilashin she knows in Myanmar, her status as “little teacher” should mean much more than simply an affectionate title. The “teacher” part should be given its due.

Reference

Kawanami, Hiroko. 2009. “Charisma, Power(s), and the Arahant Ideal in Burmese-Myanmar Buddhism.” In Asian Ethnology Volume 68, Number 2.

Related blog posts from BDG