Southeast Asia is perhaps Asia’s true melting pot of religions and cultures. Malaysia, along with Singapore and Indonesia, is a hub of multiculturalism and interfaith coexistence. These countries, along with Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand, enjoy an ancient relationship with the Buddhist faith that stretches back over two millennia. Southeast Asia is one of the most important regions for Buddhism, but has often slipped under the radar of Anglophone coverage. “Eye On Southeast Asia” seeks to provide a small corrective. While this Tea House column will interview personalities and highlight organizations and temples in Southeast Asia, it attempts to go further, analyzing the historical and contemporary trends that shaped the region’s traditions, presenting local perspectives about present problems and potential solutions.

Malaysia, Truly Asia (Asian Buddhism)?

I am in Malaysia more often now, so I take the chance to speak to as many Dharma associates as I can while here. I had a reunion with an old friend from 2018: Lim Kooi Fong, a CEO in his day job whose abiding interest over the past decade and longer has been the Buddhist Channel. In my early days covering Buddhist affairs in 2010, I used this hub frequently as a resource for events and commentary, which Lim diligently collated and presented for Buddhist writers.

Despite Malaysia’s Islamic majority, a cursory glance at the large numbers of Buddhist youth groups, along with Sunday Dhamma Schools across the nation, initially convinced me that the Buddhist population – 19.8 per cent of Malaysia’s total – was in a strong position. But Lim was quick to point out that this is only a partial picture. For example, Malaysia’s Buddhist development has been less strategic than that of its neighbor Indonesia. After independence, Buddhism in Indonesia had to adjust to the government’s demands for monotheism, resulting in a “Pancasila Buddhism” that Buddhists could unite around. Ironically, this helped to secure Buddhism’s position in the country as a spiritual pillar.

In contrast, Malaysia’s Buddhist institutions have had to bear with the Muslim majority’s indifferent attitude, including an Islamic government that has no religious strategy beyond garnering the Malay vote and cares little about collaboration with Buddhism as it sees no ideological value in it.

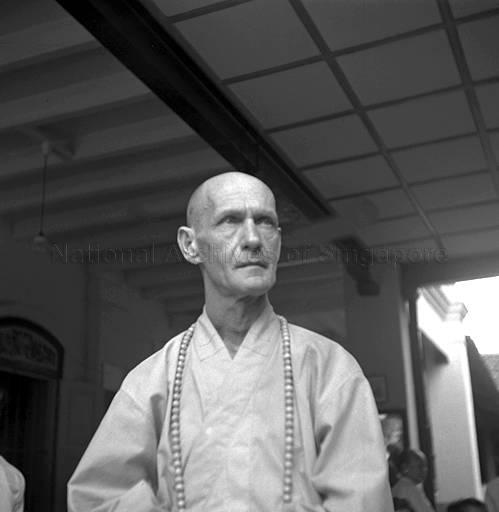

Furthermore, Lim suggested, the golden age of Malaysian Buddhism is over. This period, apparently, had “begun in the 70s and continued until the early 90s,” he said. “Things really began moving with the formation of the Federation of Malaya Buddhist Youth Fellowship (FMBYF) by Ven. Sumangalo on 24 December, 1958.” Ven. Sumangalo (1903–63), who was born as Robert Clifton, was an American monastic that mobilized youth participation in the post-independence Buddhist movement. His memorial hall is in Georgetown, Penang. Like his fellow American (and in a sense, missionary predecessor) Colonel Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907), Ven. Sumangalo saw meeting the evangelical Christian challenge with a robust, renewed pride in Buddhist affiliation as a priority.

This purpose was assisted by another crucial personality: Ven. K. Sri Dhammananda, who was not only charismatic and offered a refreshing teaching style for meditators, but also published prolifically for mass distribution. Other drivers of a “Malaysian” approach to Buddhism include layman Piya Tan (formerly Ven. Piyasilo), who now resides in Singapore. As a monk, he co-founded the Young Buddhist Association of Malaysia [YBAM] in 1970, and his prolific writing – over 40 publications – formed a kind of “philosophical” foundation for Buddhism in Malaysia. The YBAM sees Ven. Sumangalo as its spiritual predecessor and the country’s proliferation of youth groups, including the Buddhist Gem Fellowship (BGF), remains one of the Malaysian Buddhist world’s abiding strengths.

Lim believes that this renaissance ceased by the 90s due to intellectual trajectories that inevitably led to more individualistic practices being favored over community building. Not only were young people getting wealthier, but the kinds of Buddhism they began to pursue had changed. For example, the Sayadaw tradition of Vipassana – strictly meditation – became in vogue. Lim ties the solo, almost self-made path of Buddhism to the rapid economic development of the 80s and 90s and the corresponding individualism of the age.

Another friend I spoke to, translator and Sattva Project co-founder Sherab Wong, lamented the gradual weakening of a truly “Malaysian Buddhist” identity in the face of international Buddhist groups vying for a “piece” of Malaysia. “We lack our own unique substance, and for a long time have devoted our energies to Buddhist organizations that come from outside Malaysia, such as Fo Guang Shan and Tzu Chi.” There is no doubt that groups from Taiwan and elsewhere like Fo Guang Shan and Tzu Chi project an aura of foreign prestige and global influence (and larger coffers) that homegrown Malaysian groups find difficult to match. Vajrayana Buddhism has become perhaps the most popular Vehicle generally, reflecting a global dominance of the tantric traditions. Many have set up Malaysian branches, which we will be looking at later.

Both Sherab and Lim argue that Malaysian Buddhism is in urgent need of intellectual revitalization. “I believe Malaysian Buddhism is very active, but all this energy is going nowhere, with little indication of a general direction,” argues Sherab. Old dichotomies dating back to the postcolonial era (lay versus monastic, scholar versus practitioner, and traditional versus modern) continue to be recycled in literature and public discourse, and it is becoming more urgent that these debates be transcended so that the ground may be cleared for newer, contemporary priorities. And with no Dhammananda-like figure to rally around, it is not immediately clear what one means by “Malaysian Buddhism” – even as activities and events in the country paradoxically continue to be vibrant and frequent.

See more

Related features from BDG

Mahabhikksu Ashin Jinnarakkhita: The Father of Modern Indonesian Buddhism

Rediscovering an Ancient Heritage in Indonesia