Reviving the Theravada Bhikkhuni Sangha has evolved into a global initiative since the 1980s, transcending geographical boundaries and fostering international camaraderie and cooperation. This year, as India and Thailand celebrate 150 years of friendship, King Rama X commemorated this historic alliance, underscoring the enduring bonds between the two nations. Amidst these festivities, Thailand announced a pioneering training program encompassing both Indian bhikkhus and bhikkhunis, heralding a new era in the annals of Thai Buddhism. The program witnessed participation, with approximately 30 Indian bhikkhus, 40 sramaners, 28 bhikkhunis, and 26 sramaneris engaging in transformative learning experiences.

The commencement of the 3-month training program for Indian bhikkhus and the 1-month program for Indian female monastics began on 1st April. This was a significant milestone in the collaborative journey of the dual sangha. While arrangements for training Indian bhikkhus were made in Chiang Mai, female monastics stayed in the tranquil surroundings of the Sisaket forest meditation center until 30th April.

A grand celebration was organized on 4th April, where the royal family offered a generous gesture by graciously donating robes (dana) to the Indian bhikkhus, symbolizing Thailand’s profound reverence for the shared legacy of Theravada Buddhism. In a gesture of inclusivity, robes were also dispatched to the Sisaket Vihara, extending the same honor to the bhikkhunis and newly ordained sramners and sramneris. These robes, known as kasaya chivar in the Theravada tradition, hold immense significance, serving as a tangible link to the lineage and teachings passed down from the time of the Buddha-era. The robes sent to female monastics were adorned with the same colors, signifying equality and unity within the Sangha.

Thailand’s historical stance against bhikkhuni ordination has been marked by stringent regulations. A decree dating back to 1928 from the Ecclesiastical Council of Thailand denied equal rights for men and women in ordination, explicitly stating, “No woman can be ordained as a Theravada Buddhist nun or bhikkhuni in Thailand.” Furthermore, the Council issued a stern warning, decreeing punishment for any monk who helped to ordain of female monks, despite that all extant Vinayas have permit dual ordination as well as ordination of women by male monastics.

Consequently, women seeking to serve the Dhamma were compelled to become maechi, women monastics donning white robes. However, despite their dedication, maechis were deprived of the full identity and recognition accorded to ordained bhikkhunis. Moreover, women adorned in kasaya chivar, symbolic of fully ordained bhikkhunis, were prohibited, underscoring the institutional barriers to gender equality within the Thai Buddhist community.

It has been a few decades since Thailand witnessed the resurgence of the Bhikkhuni Sangha, when Dr. Chatsuman received higher ordination as Bhikkhuni Dhammananda against formidable odds. Her transformative journey, which commenced with her samaneri ordination in 2001 and culminated in her full ordination in Sri Lanka in 2003, stands as a testament to her unyielding commitment to gender equality within the Sangha.

Ven. Dhammananda has since emerged as a prominent advocate for Bhikkhuni ordination, spearheading efforts to empower women within the Buddhist community. Through her visionary leadership, the Songdhammakalyani Buddhist Women’s Training Centre in Thailand is now a sanctuary of empowerment, offering women the opportunity for ordination and training as bhikkhunis, adorned in the revered orange robes.

Currently, both the traditions of bhikkhunis and maechis coexist in Thailand. During this monastic training program in Thailand, for the very first time, 72 Indian women embraced the maechi tradition, signifying a cross-cultural celebration embraced by the Indian community. However, this cultural fusion has not escaped criticism. The introduction of the maechi culture to India, where the tradition is non-existent, has sparked intense feminist debate. Indian bhikkhunis fear it could jeopardize the identity of bhikkhunis, who are already grappling with a struggle for acknowledgment and recognition within society. The influx of a new foreign culture could potentially erode the ancient tradition, as seen in other Theravada countries.

In various Theravada countries, similar to maechis in Thai Buddhism, women renunciants don white or pink robes. In Sri Lankan Buddhism, they are known as dasa sheel mata, while in Burmese Buddhism, they are called thilashin. In Nepal and Laos, they are referred to as guruma, and at the Amaravati Buddhist Monastery in England, they are known as siladharas. In Myanmar, Ten-precepts ordained nuns, or the sayalays, typically wear pink robes; however, they are not considered fully ordained bhikkhunis.

Despite the absence of an explicit statement regarding the shift in policy from the 1928 decree, the acknowledgment and invitation extended to Indian bhikkhunis to participate in the training program in Thailand and sending orange robes for Indian bhikkhunis and sramaneris marks an appreciating step towards equality. This gesture offers a glimmer of hope and optimism, indicative of changing scenarios within the Thai monastic community. It paves the way for greater inclusivity, fostering an environment where women can assert their rightful place within the Sangha and contribute meaningfully to the Buddhist tradition.

The resurgence of the Bhikkhuni Sangha extends beyond Thailand to women in Sri Lanka, India, and other Theravada countries challenging age-old norms to reclaim their rightful place in the Sangha. Despite facing legal hurdles and social and cultural resistance, these women insist on the right to equal recognition and respect within Buddhist communities. Today we see a new batch of bhikkhunis in Sri Lanka, India, England, and Bangladesh who are writing and publishing about their existence. They are connected to bhikkhunis across nations through social media and organizations like Sakyadhita International.

In India, the revival of the Bhikkhuni Sangha holds profound significance, deeply rooted in the country’s historical and philosophical ties to Buddhism. The Ambedkarite Buddhists, followers of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, were pivotal in spearheading this resurgence. By challenging the entrenched social hierarchy perpetuated by the caste system, they advocate for equality and liberation within the Buddhist community.

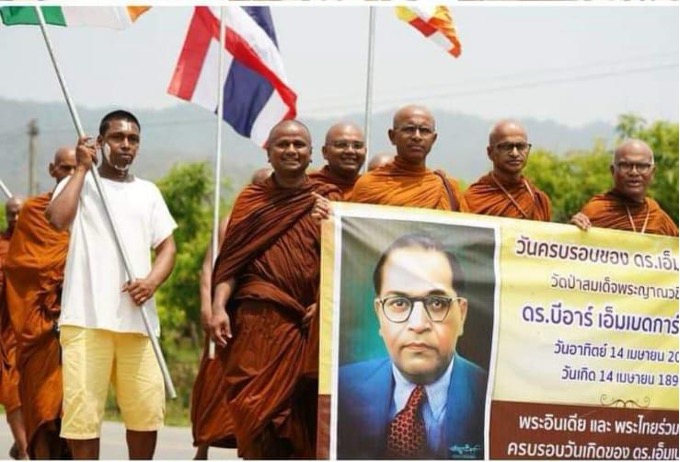

A notable highlight of the Thailand program was the commemoration of Dr. Ambedkar’s birth anniversary on 4 April 2024 by both Indian and Thai monastics. This event underscored the program’s intercultural dimension, emphasizing the shared values of equality and social justice between the two nations.

In India, the Mahaprajatai Gautami Bhikkhuni Training Centre in Nagpur, led by Bhante Suniti Bhikkhuni and Bhante Vijaya Maitriya Bhikkhuni, played a pivotal role in nurturing the Bhikkhuni Sangha. Through their unwavering dedication, they have not only ordained and trained numerous bhikkhunis but have also extended mental health counseling and outreach to marginalized communities across the nation.

As we commemorate Vesak and delve into the teachings of the Buddha, let us reflect on his steadfast commitment to gender equality and liberation for all beings. The revival of the Bhikkhuni Sangha is far more than a mere historical footnote; it stands as a living testament to the enduring spirit of liberation and empowerment within the Buddhist tradition. Through international collaboration and policy shifts, we are witnessing a transformative movement that embraces diversity, inclusion, and equality within the Sangha.