While Buddhism teaches us about our own suffering and the cessation of suffering, it also instructs us on how to live with others in harmony. As I get older, it becomes increasingly ironic to me that so much time and energy is spent struggling with people, when in fact being at peace with and feeling connected to my community leads to a richer, fuller life.

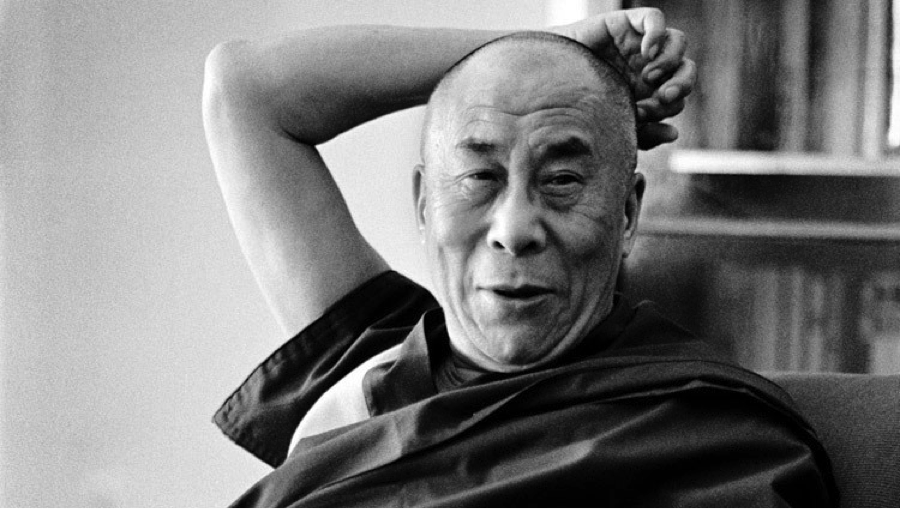

In saying this, I do not mean that we benefit from avoiding conflict at any cost. On the contrary, taking a passive attitude often prevents us from dealing appropriately with a given situation. Instead, socially engaged Buddhists would have us approach conflict as an opportunity to put our beliefs into practice. This sentiment is beautifully expressed by the Dalai Lama:

“Now, there are many, many people in the world, but relatively few with whom we interact, and even fewer who cause us problems. So, when you come across such a chance for practicing patience and tolerance, you should treat it with gratitude. It is rare. Just as having unexpectedly found a treasure in your own house, you should be happy and grateful to your enemy for providing that precious opportunity.”

In this way a so-called enemy becomes a treasure, a chance to transform the roots of suffering and conflict within ourselves. Interestingly, a number of mediators have drawn similarities between their line of work and Buddhist practice. In fact, Director of the Center for Dispute Resolution Kenneth Cloke is of the view that meditation and mediation go hand in hand. He explains:

“Trying to meditate without addressing underlying conflicts makes our practice superficial, frustrating, and incomplete. Trying to mediate without cultivating awareness traps us at the surface of our conflicts and ignores what is taking place in their depths. When we combine these practices, we are led to the deeper middle way, and to profound insights, both for ourselves and others.”

Susan Hayward, a senior advisor for religion and inclusive societies at the U.S. Institute of Peace, is also a proponent of combining mediation with Buddhism. She praises both the value in each party being aware of their own emotions without giving in to them, and the value in being attentive to what the other is saying. She writes:

“Questions such as ‘What is something you are willing to let go of in order to help us move towards a solution?’ can trigger the Buddhist ecosystem of thought around ideas of attachment and the value of non-attachment, yet without being heavy-handed.”

According to Buddhism there are three culprits when it comes to suffering and conflict — these are known as the three poisons (kleshas) of greed (raga), aversion (dvesha) and delusion (moha). In order to combat these poisons one can practice generosity (dāna), loving-kindness (mettā) and wisdom (prajna) respectively. While meditation can help us to develop these qualities, there may be no better opportunity to test our virtuosity than when we find ourselves in the midst of a conflict.

References