“The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of Ariana, but also of India, as Apollodorus of Artemita says: and more tribes were subdued by them than by Alexander — by Menander in particular. . . ”

– Strabo, Geographia (Book XI, Chapter 11)

When we first set off in Alexander the Great’s eastward footsteps, we discovered how he unwittingly became the Macedonian bridge between Egypt and India. We saw how Alexander’s contemporary troupe of philosophers, among them Pyrrho, might have met monks practicing an iteration of Early Buddhist meditative techniques. But how did Greek colonists on the far side of Alexander’s world end up forming the Indo-Greek Kingdom: one of the most powerful, prosperous, and Buddhist hybrid cultures of the Classical Era?

Driven by an insatiable desire to surpass Achilles himself, Alexander the Great set off on a grand campaign, at the head of a Macedonian-led coalition to take down the Achaemenid Persian empire. . . and unwittingly, after his sudden death at age 32, ushered in the Hellenistic Age across north Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. There were already Persian-ruled Greeks around, but the growth of this continental Hellenism was due in no small part to the rapid rise of the Indo-Greek Kingdom. (c. 200 BC–c. 10 AD)

This loose collection of communities arose after a complicated serious of political, military, and cultural events. Seleucus I Nicator (359–281 BC), one of Alexander’s successor generals, carved up Alexander’s empire after the latter’s death in 323 BC. He then made military and diplomatic contact with Chandragupta Maurya (350–295 BCE), founder of the Mauryan Empire and grandfather to Ashoka the Great, eventually securing a marriage alliance with Chandragupta.

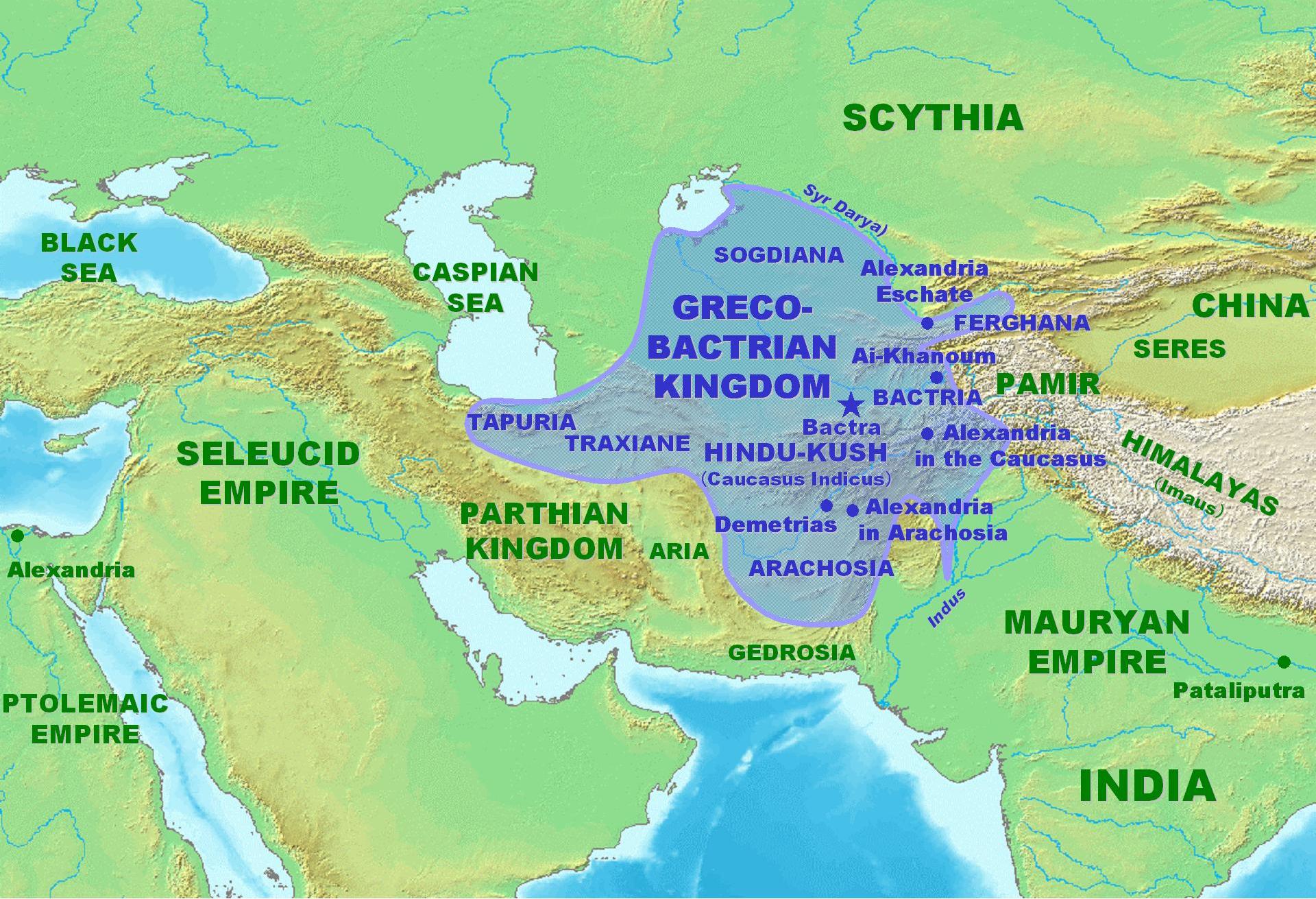

Then, around 250 BC, Diodotus I the satrap (governor) of Bactria, seceded from the Seleucid Empire, ushering in the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. Bactria was prosperous, powerful, and outward looking: when Zhang Qian, the famous Han ambassador westward, visited Bactria later in 126 BC, the region had a sophisticated economy, with people in occupations similar to those of the Chinese (perhaps as generous a compliment as any Han representative could think of). Its wealth was noted by Greeks and Chinese alike, and they produced some of the finest coinage of the period. The thriving kingdom also had a flourishing hybrid, Indo-Greek culture, with some of the most beautiful sculpture and architecture in Eurasia being produced.

Under the fourth king, Demetrius I of Bactria (c. 222 BC–c. 167 BC), the Greco-Bactrians invaded large swathes of Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent against the Shunga Empire (187–78 BC), which by then had toppled the famed Mauryan dynasty. It is possible that the Greco-Bactrians were trying to stop the Shungas from attacking Greek colonists that had settled in onetime Mauryan region.

With this new promise of military protection (and the Greco-Bactrians had formidable armies), the Indo-Greek communities formerly under the protection of the Mauryans reconstituted as a collection of states led by their own kings, ruling from Greek colonies like Taxila, Sagala (modern-day Sialkot), and Pushkalavati, the capital of the ancient Gandhara kingdom. Under these Indo-Greek kings, who saw themselves as distinct from the Greco-Bactrians, Buddhism flourished as a royally patronized spiritual tradition. We know that Menander followed in this tradition of militarily powerful, culturally receptive leaders. Strabo mentions these legendary general-kings: “those who came after Alexander.” Demetrius I probably managed to push as far as the Ganges, while it was Menander I Soter (c. 180 BC – 130 BC) who fought his way to Pataliputra, capital of the Shunga nemesis.

Ruling over modern-day Punjab, Menander was one of the most prolific patrons of Buddhism. If we read the Milindapanha in the Khuddaka Nikāya, he probably also had a reputation for philosophical insight and intelligence. From the moment he meets the protagonist of the text, a monk called Nagasena, he challenges him:

“If, bhante Nāgasena, no person obtains, who therefore gives you robes, alms food, lodgings and medicinal requisites? Who enjoys the use of them? Who guards their ethical behaviour? Who engages in meditation? Who attains the path and fruit of Nibbāna? Who kills a living being? Who takes what is not given? Who commits wrong conduct in sensual pleasures? Who speaks falsely? Who drinks intoxicants? Who commits any of the five deeds that bear fruit without delay? Therefore, there is nothing wholesome, nothing unwholesome. There is no doer of wholesome and unwholesome deeds, nor anyone who makes another do wholesome or unwholesome deeds. There is no fruit or result of good or bad deeds. If, venerable Nāgasena, there was someone who caused you to die, there is no killing of living beings for that person. Venerable Nāgasena, there is no teacher, no preceptor, and no ordination for you.”

This lengthy inquiry, of course, cuts to one of the core philosophical dilemmas of Buddhism, that is, what constitutes continuity if there is no self.

The inquiries made by Menander, as well as Nagasena’s counterpoints, contain interesting narrative highlights, such as the mention of Menander’s five hundred elite “Bactrian Greeks” or yona who may have formed a corps of royal guards along with a main force of cavalry, chariots, and elephants. Despite their relatively light textual footprint, we must be grateful for the fact that they left behind a considerable range of physical evidence, from Yavana-sponsored Buddhist caves to stupas, sculptures, and architecture and art.

The Milindapanha even says that after his dialogue with Nagasena, he continued practicing Buddhism and became an arhat. To date, the location of his relics remains unknown. Perhaps one day, discovering his tomb will unearth some groundbreaking answers.

Numismatics reveals that Indo-Greek kings like Menander styled themselves with diverse titles on their coins. Perhaps these two, the Greek “basileus” and Sanskrit “maharaja,” are representative of the cultural hybridity and dual identity of the Indo-Greeks. They were Hellenistic in the sense that they had some memory of their forebears being colonists. . . and perhaps even tales of a great conqueror. Chandragupta Maurya famously aspired to match Alexander. But the Macedonian and his entourage of philosophers like Pyrrho would have barely recognized the Indo-Greeks: revering and worshipping a serene figure of an Indic sage (along with other local and Hellenistic deities), speaking a tongue far removed from Macedonian, and being led by men like Menander, who by every historical deduction, was not just a formidable commander, but a pious Buddhist.

As the Shinkot casket (one of the oldest dated reliquary from Gandhara) proclaims, he was “Mahārāja Minadra,” the great king.

See more

Geographia (Book XI, Chapter 11) (University of Chicago)

Exposition Question 1. Paññattipañha (SuttaCentral)

Related blog posts from BDG

Pyrrho: Greek hints of the Buddha’s Awakening

The Shakya Sage and the Son of Ra