The tragedy of Myanmar’s displacement of Rohingya Muslims, aside from its complex ethnic, historical, and religious backdrop, is exacerbated by two essential political realities. The first is that Western media and governments erroneously saw what it wished to see in Aung San Suu Kyi throughout her difficult struggle against the Burmese junta. When she decided to become the country’s state counselor in 2016, she did so under a constitution that favors the continuity of military authority and acquiesced to a context of government that does not fit with the simplified dichotomy of oppressor versus oppressed. Myanmar is also far more ethnically and politically diverse than many care to appreciate.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s father was the founder of Myanmar’s independence movement and the modern Burmese army; her mother was a high-level diplomat in the newly created country. She has the full backing of the Buddhist sangha and its representative organization, the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee. She is therefore understandably and justifiably a nationalist. As a statesman and diplomat, her priority is the political integrity of Myanmar, nothing more and nothing less. So she isn’t unaware of international sentiment turning against her; she’s as cosmopolitan as they come. Rather, it’s far more likely that she sees the criticism against her and has decided that there are more pressing urgencies. Such hard choices are dilemmas that haunt many a politician.

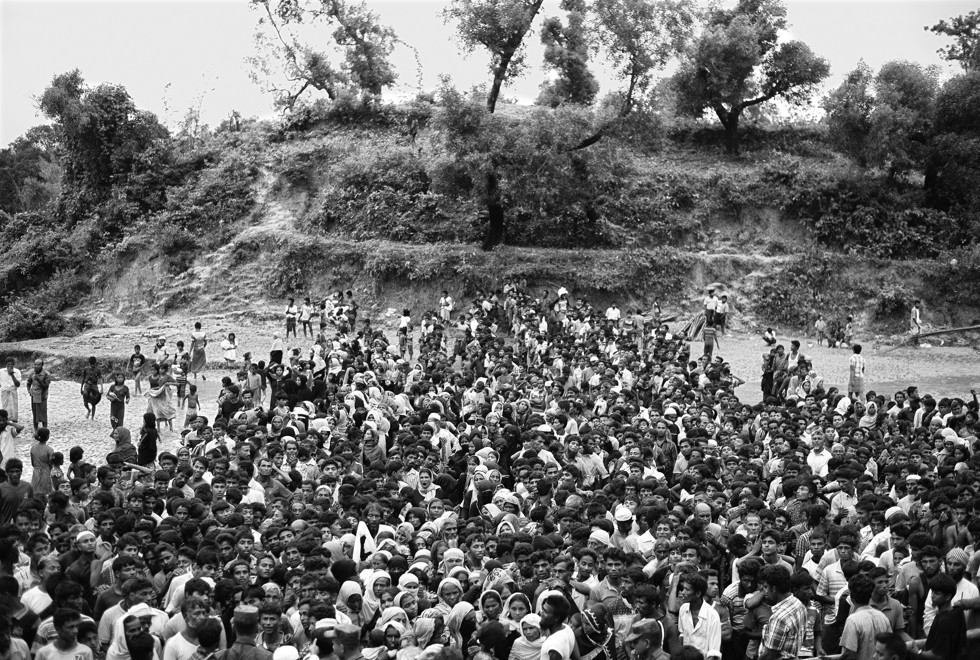

Related to the first issue is that fact that for the immediate future, the Rohingya will sadly remain stateless. There seems to be no possibility of a quick settlement. The country that has been shouldering much of this chaotic transition is Bangladesh, which has built up to 23 camps for Rohingya that have been streaming across the border since late August. On 6 October it announced that it would build a single, massive camp to shelter the more than 800,000 desperate people seeking asylum. With the conflict in Myanmar set to worsen, there does not seem any room for regional Buddhists to maneuver except to assuage the humanitarian suffering without putting too much on the line diplomatically.

We also know that Buddhist organizations in Bangladesh are chipping in to alleviate the rapidly unfolding crisis: the United Forum of Buddhists in Bangladesh, for example, collected money for the lanterns and other parts of Probarona Purnima festival in Dhaka (the second-largest annual Buddhist feast) to a relief fund for the evacuees. Shima Bihar, a 300-year-old monastery in Ramu, helped to distribute supplies to 1,500 Rohingya people, including dry goods and water (the army and approved NGOs have since assumed the role). It also provided blood collection service for hospitals that were caring for injured refugees, including those who have been wounded in the recent fighting with Myanmar government forces.

Politics should be a lesser consideration for Buddhists. However, one cannot ignore the political optics in light of Bangladesh’s Muslim majority and the inflamed nationalism in Myanmar. On 8 September, the United Forum formed a human chain in front of the Jatiya Press Club in Dhaka, urging non-violence but also voicing concern over rumors spreading on social media accusing Bangladeshi Buddhists of being some kind of Islamic fifth column. With not a few Buddhist organizations in Bangladesh mobilizing and protesting against the violence, 550 police have been deployed at 145 Buddhist temples from Chittagong to Dhaka to prevent violence between ethnic groups.

I would argue that the Buddhists who have done their part to help the Rohingya, often taking direct action, are grossly underreported. It’s easier to focus solely on the failures of the Burmese administration or the violent nationalism of a vocal minority of Buddhist monks and laypeople. What isn’t so easy is providing nuance in a rapidly deteriorating situation where Buddhists find themselves on opposite sides—for better or for worse. We should look to these leaders of conscience, both within Bangladesh and within Myanmar, for answers as to how a settlement for the Rohingya might be reached.

Bangladesh’s Buddhist followers are communicating a message of brotherly compassion and putting it into action. On one side, we have Muslim refugees fleeing a Buddhist-majority country. On the other, well-integrated Buddhists in an Islamic society are helping exiles of a different faith. There is a message of hope in here somewhere, and a narrative positing reconciliation between Rohingya and Burmese people needs to overcome that of recurring hatred and division.

See more

Bangladesh to build one of world’s largest refugee camps for 800,000 Rohingya (The Guardian)

Bangladesh’s Buddhists throw support behind Rohingyas despite lingering fears (Channel NewsAsia)

Bangladeshi Buddhists to give up festivity for Rohingya refugees (UCA News)

Stop atrocities, Bangladesh Buddhists urge Myanmar (The Daily Star)

Thank you for this. And for drawing our attention to the help given the refugees by Buddhists in Bangladesh. As for Aung San Suu Kyi, I take your points, but I still find it difficult to see how a sincere follower if the dharma could be ‘understandably and justifiably a nationalist’.

Nationalism is seen as something quite evil in the European mainstream – after all, it led to two World Wars. But nationalism, for Asians, was an imported ideological weapon learned from the Europeans that colonized their land. It provided the intellectual and political means to do away with foreign imperialism (the aforementioned nationalism that led to the ruin of the European empires didn’t hurt, either). Therefore, nationalism, while volatile and not all beneficial (look at imperial Japan), was crucial to forming the identity of the Asian nations as they stand today – for better or for worse.

I think it’s all a matter of degrees. So personally, I’m very disappointed by the extreme anti-Muslim activists in Myanmar. However, given her unique political bind, Aung San Suu Kyi is quite an extraordinary case.