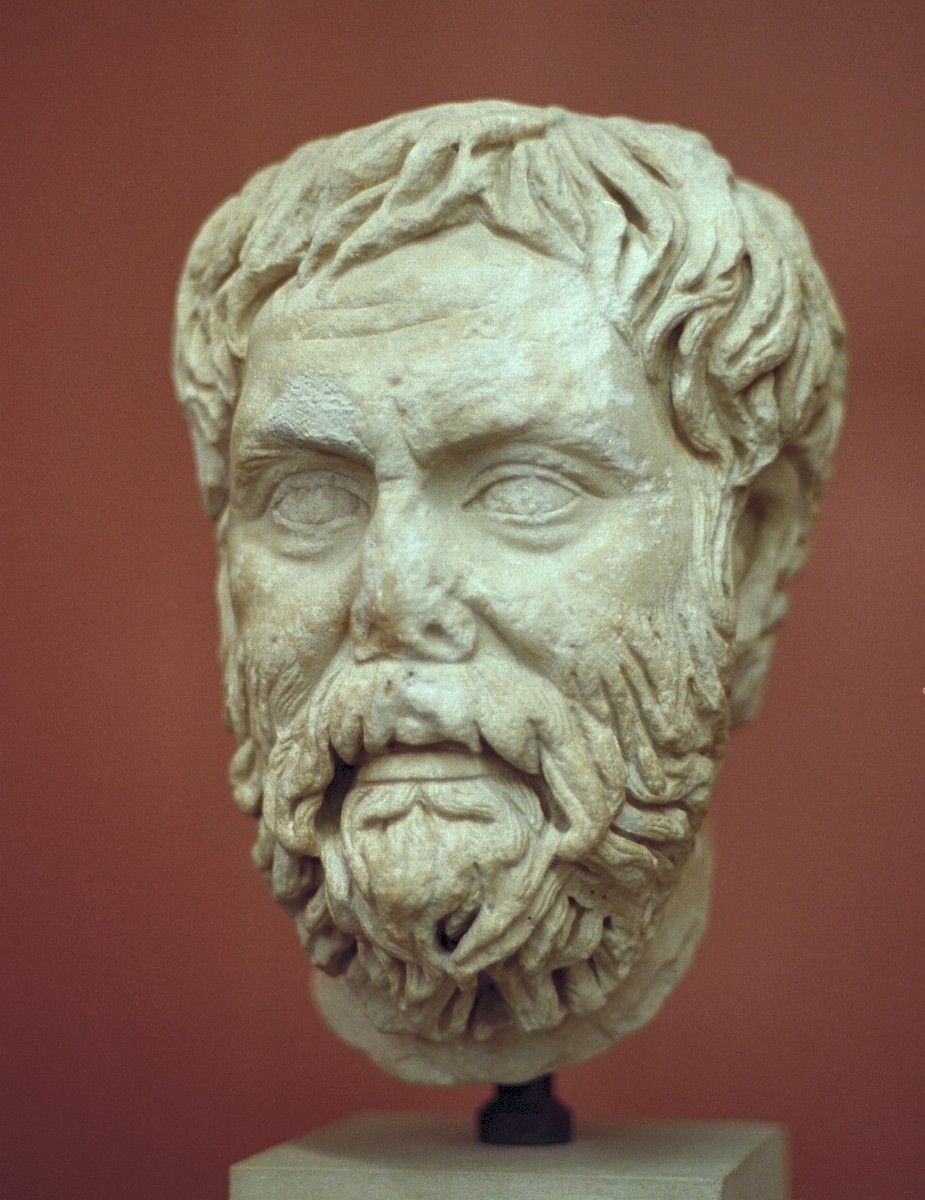

Despite his hunger for eternal glory, his determination to defeat the Persians, and his love of war, Alexander the Great was, like any member of the Macedonian royalty or aristocracy of the day, a student of philosophy. He was famously tutored by Aristotle, and when he began his epic campaign to confront and conquer the Achaemenid Empire, there was one philosopher that travelled with him. This philosopher, Pyrrho (c. 365–360 BC–c. 275–270 BC), would found a school (Pyrrhonism) that was a form of early Western scepticism.

I like reading Christopher Beckwith, even if I believe his historical assessments have become increasingly quirky and historically questionable since 2005. His book Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia (2017) argues that among the eight major schools of philosophy that could be tangibly identified in ancient northwestern India and Central Asia, Pyrrho seems to have encountered several expressions of early Buddhism and absorbed their ideas into his philosophy.

The Stanford Encylopedia of Philosophy says that Diogenes Laertius (fl. 3rd century AD) wrote about how Pyrrho met “gumnosophistai” or “naked wise men” while on Alexander’s expedition in India. There was most definitely some kind of exchange between the likes of Pyrrho and these Indian teachers, whether they were brahmins, Buddhist or Jain monks, or some other school’s representatives entirely. Diogenes Laertius, admittedly from many centuries later, ascribed to Pyrrho an attitude of apatheia and eukolia, “freedom from emotion” and “contentedness.” The word apatheia appears in other sources to describe Pyrrho’s attitude as well, and the combination of the two terms seems to describe something close to the state cultivated by Pyrrho.

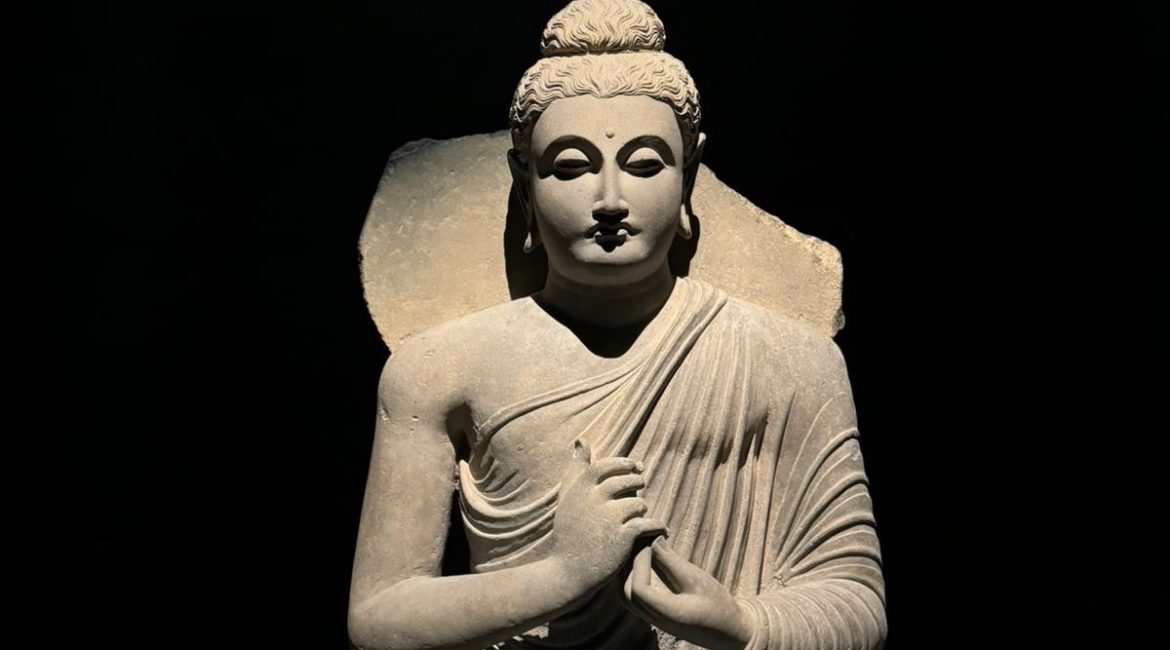

It must be said that Buddhism would not characterize itself as a sceptical philosophical tradition. It is an anti-nihilist and anti-theistic worldview. The Buddha’s thought embraced presuppositions that had been in place for hundreds of years before his time: rebirth, the idea that this reality was somehow illusory, and that liberation somehow involved the ending of rebirth in this reality.

The fact that Pyrrho made no reference to the Middle Way is another important absence of evidence against his purported Buddhist influence. The Middle Way, in my view, is the core constituent of Buddhist teaching, since the suttas speak of the Buddha’s realization of the Middle Way as something that came before even the basic teachings like Dependent Origination (chronologically, Gautama realized the Middle Way after being saved by Sujata and rejecting asceticism).

There is little to indicate Pyrrho accepted rebirth, any idea of a “Middle Way” in the context of meditation, or core Buddhist ideals for cultivation like compassion and wisdom. Buddhism can only be meaningfully said to have had an influence on Pyrrho if the philosopher preached some kind of liberation (even if it was not from a cyclical realm of existence). Is there any trace of this found in the rather unsatisfactory and fragmented literature about the Greek philosopher?

The nikāya-āgamas (a composite word for the earliest Buddhist texts) present a complete stopping of the mind’s activities, or the cessation of thoughts, as the ultimate goal of meditation. Some kind of cessation of all perceptions and feelings, or nirodha (and which happens while the practitioner is alive and breathing), is presented as the apophatic apex of meditative attainment that opens that path to Nirvana.

Ultimately, we do not know the identities of the sages Pyrrho might have met in India, but Pyrrho and other Greek thinkers were been impressed by both second-hand reports and firsthand observation of the Indian gumnosophistai’s striking “impassivity” and “insensitivity to pain and hardship.” The Stanford Encylopedia of Philosophy’s use of these two words, insensitivity and impassivity, seems to me to be a clue. Was this impassivity and insensitivity (in the sense of being free from external stimuli) some kind of linguistic expression, no matter how flawed, of the meditative attainment that the gumnosophistai had reached? The Early Buddhist texts talk of enlightened meditators that possess a body and senses, but at the same time their “inner” perspective is completely apophatic, having transcended these categories.

Should there be any future revelation that Pyrrho encountered and was inspired by an Early Buddhist concept of the cessation of all thought and feeling, then we will know that the Greeks brought back home with them an ancient, authentic form of Buddhist thought. But perhaps we need not look even so far beyond ancient India’s borders. The Indo-Greek Kingdom (200 BC–10 AD) was a hotbed of philosophical fecundity, and its greatest king, Menander, bridged India and Greece in a manner that neither Alexander nor Pyrrho could match. Through his philosophical questions, Menander, or at least his name, would attain immortality in the very canon of the Early Buddhist texts.

Related blog posts from BDG

The Shakya Sage and the Son of Ra