I have been re-enchanted by the cyberpunk genre recently. When I want to switch off mentally I play the rhythm game, Cytus 2, in which the story is inspired by themes like robotics, dysfunctional societies, and alienation. On Netflix, I have been catching up with the aptly named Cyberpunk: Edgerunners, which in many ways synthesizes some of the core prophetic ideas of cyberpunk into a richly animated series: cybernetic technology and humans as androids, the military-industrial complex, economic and social inequality, and embers of the human spirit’s yearning for goodness, love, and warmth in a world that has no place for such things.

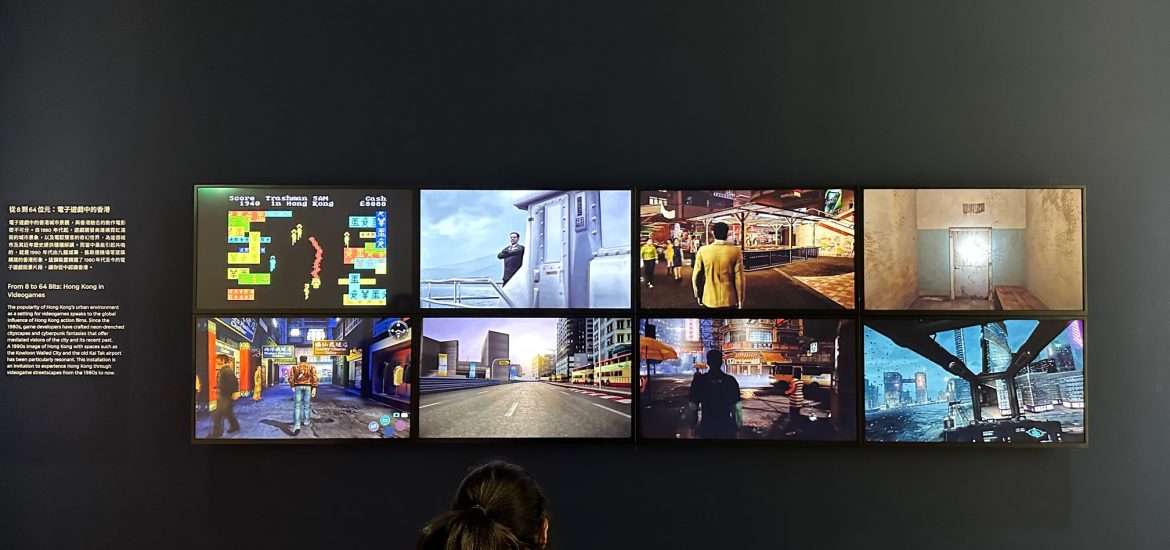

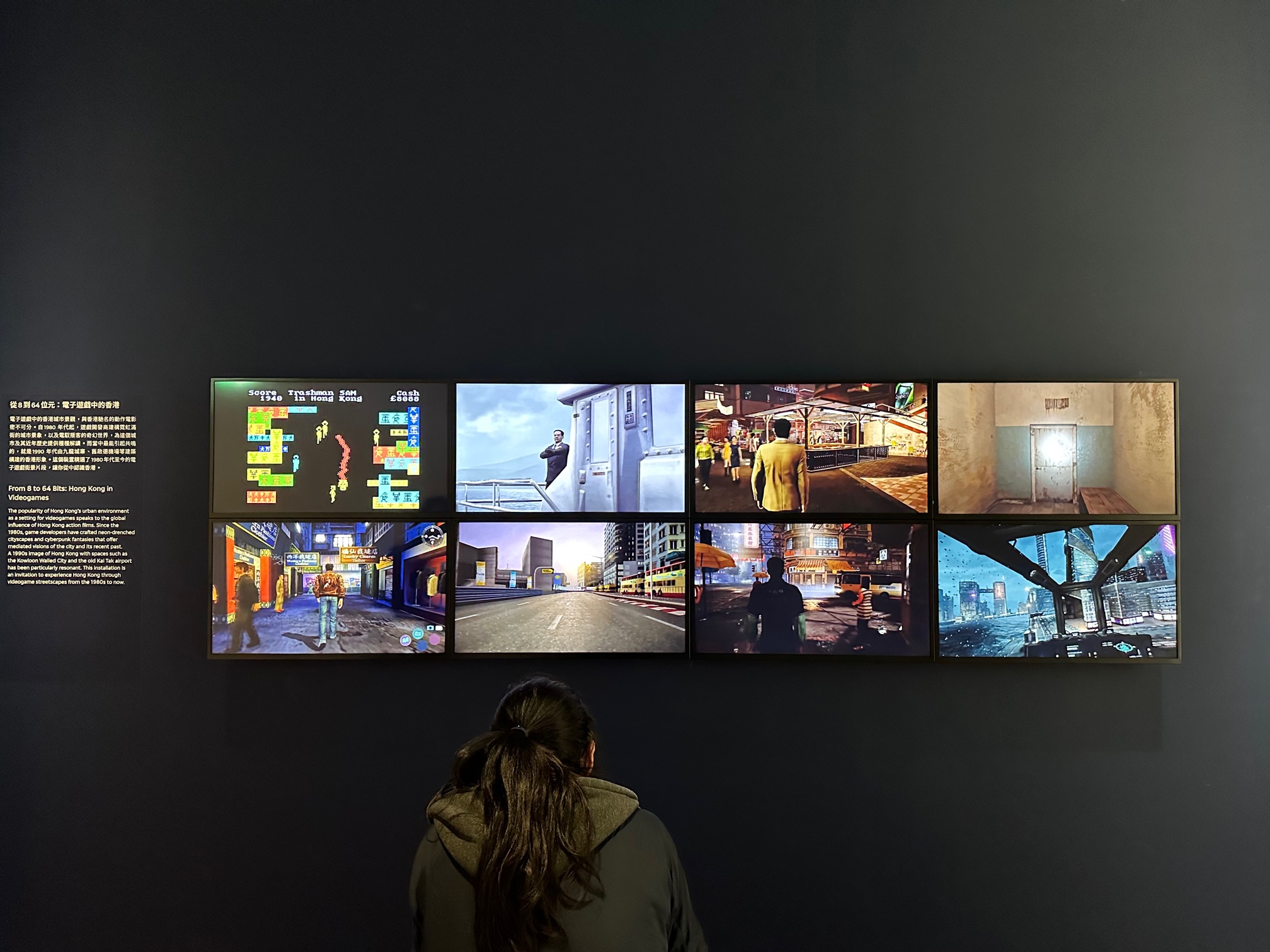

M+, Hong Kong’s newest and largest establishment for contemporary art, is showcasing a marquee exhibition called “Here and Beyond: The visual culture of our city from the 1960s to now.” One of its most striking installations reminds me very much of cyberpunk, as it showcases the various video games that featured Hong Kong’s urban scenery over the decades, it cannot help but exude a cyberpunk aesthetic. Game developers and writers have always been upfront about the atmospheric imagery of Hong Kong as a city that never sleeps, is controlled by a small handful of powerful companies, and has a dark, seedy underbelly. The grittiness of downtown streets, digital technology, and the buildings and environments of the less well-off are most certainly striking to any photographer or artist. The high-tech feel of the Victoria Harbour skyline, along with the glittering glamor of the city’s wealthy, all contribute to the feel of a city with a special destiny, for better or for worse.

“Here and Beyond: The visual culture of our city from the 1960s to now” is free, launched on 12 November 2021, and will remain until 11 June. Its displays and art are nostalgic and hearken back to a time that is actually quite recent, yet seems already long-lost to citizens of a city wherein entire eras are measured by decades; buildings built to last centuries are torn down after less than a hundred years, Many will remember that most colonial-era buildings were torn down by the sixties, completely transforming the waterfront that defined the port city’s colonial identity.

There are some real gems: architectural plans for some of Hong Kong’s most iconic buildings, including the Jardines headquarters and City Hall, replicas of unique oddities like the Paddling Home (漂流家室) by artist Kacey Wong, which is a unique commentary on not just the Hong Kong spirit and ability to make anything, anywhere work, but the undercurrent of tragedy in the very necessity of having to do it, given the city’s unliveability for a sizable minority of the poorer population.

There are many beautiful and striking works at the exhibit, from paintings commenting on the social situation of Hong Kong to installations that detail the architectural evolution of urban spaces. One minor problem I found is the fact that each installation is “self-contained,” that is, while the items might tell a story, I could not identify an overarching narrative that outlined the contours of Hongkongers’ identity from the 1960s to the present day.

I would contend that identity for Hong Kong does not exist, or at least is much harder to identify than Hong Kong culture, which is often conflated with identity. This one is for the social anthropologists and cultural critics, but I believe that Hong Kong being the primary interface between China and the West is simply its identity, which has lent the city an almost mythic air. Yet “East-West” platitudes are not really distinctive Hong Kong culture, or at least, they make for rather short-lived conceptions of what Hong Kong is and can be.

My own concern is that whatever one can say about Hong Kong, one can equally say about New York, London, Dubai, and so on. As I stay in Malaysia and visit Kuala Lumpur more often, I feel that even hybridity is not something that Hong Kong can uniquely claim, whether in terms of the East-West clash or the city-countryside contrast.

What is unique to me about Hong Kong is its proximity to a futuristic literary concept that was at first only skin-deep (in terms of the skyline and society’s contours), but is now on the verge of being realized through the transition to cashless payments, the rise of financing for companies in AI, fintech, NFTs, and virtual and augmented reality (I will be writing about one such AI company based in my very own suburb of Tsuen Wan soon), and the establishment of a transnational, stateless elite that lives in moments of tension as well as cooperation with our technocratic leaders.

True, the private clubs still thrive and remain markers of prestige and wealth, but their place in artistic and cultural consciousness has been largely displaced by a crucial sociological indicator of “cyberpunk” society: private rootlessness. One freely chooses to be rootless or is compelled to be by birth and circumstance. The “mark-less,” incognito glass and metal of today reflects Hong Kong’s understanding of itself as a global city, detached from locality even as its people desperately try to regain it through art and culture to retain some uniqueness.

To call oneself a Hongkonger is to make a political statement, whether one seeks Chinese roots or reaches back to a long-lost colonial past. Either way, Hong Kong is where people come and go, even for people that stay and love it their whole lives. That coming and going, that constant movement, endless and sometimes disorienting changes amidst things that unrelentingly stay the same, like the city’s materialism and hunger for wealth and power: that is what makes Hong Kong unique, that feeling of living life on the edge, embracing the romance and charisma, the paradoxes and the drama, and the poignancy and romance.

Related features from BDG

*enter* Digital Bodhisattva _/\_