As the United States launches its long-awaited trade war against China, I wonder whether something subtler, but just as significant, is bubbling under the already tumultuous surface. I pondered for a short while whether this observation held any water. After all, indirect pressures or persuasions, rather than outright pronunciations and their enforcement, characterize the influence of religion in policymaking circles. It’s important for journalists of religion not to overreach about what they discern in the deeper corners of national life.

However, if the 21st century is to be defined by the multidimensional tension and competition between China and the US, we should look beyond the typical measures by which conflict is gauged: economic, military, and cultural. Notably, we should have a look at how the gradual move towards a Dominionist theocracy in America and the ascent of Buddhism as China’s “soul power” could well inform the clash of values that have already burst into the open across the international stage.

Neither phenomenon is an obscure trend. Prominent journalists have covered them widely in mainstream papers. The near-inevitable nomination of a conservative justice to the US Supreme Court (which will have an impact on American life for far longer than any congressional or presidential cycle) has made The Guardian’s Suzanne Moore draw parallels between the fictional country of Gilead (where women are breeding slaves) in The Handmaid’s Tale and the current dominance of the Trump agenda (whose advocates often invoke the Bible to justify the policies) across all branches of American government.

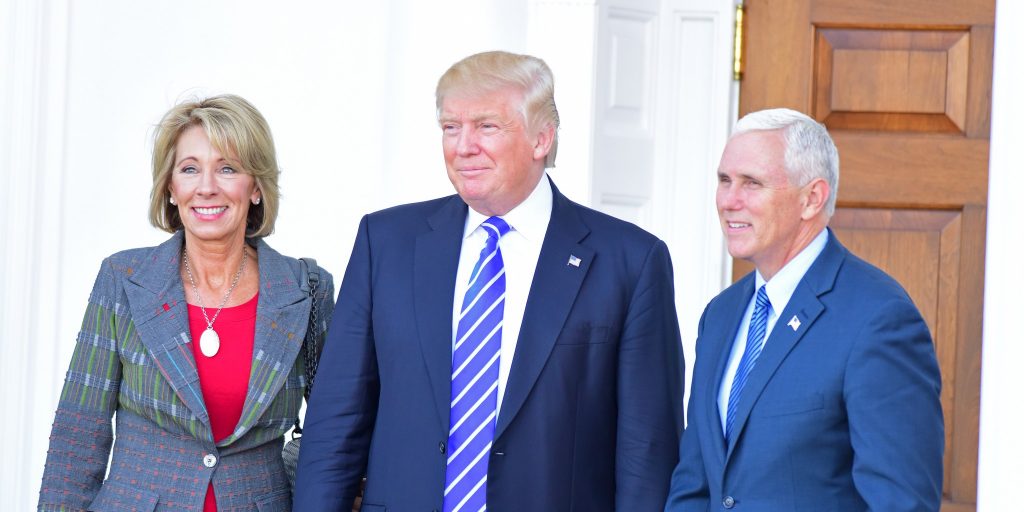

The latter is buttressed, notably, by many of America’s evangelical Christian leaders and believers, who have overlooked Trump’s often un-Christian behavior and morality by pointing to his support for right-wing Christian causes: unconditional support for Israel in its conflict with Palestine and Iran (evangelicals also predict the conversion of the Jewish nation to Christianity at the end of the world), a gradual rollback of pro-abortion legislation domestically, and, of course, the relentless promotion of America itself as a Judeo-Christian experiment, stripped of all secular imprints. Susan Jacoby writes in The New York Times how many in Trump’s administration, such as education secretary Betsy DeVos, are attempting to tear down the wall between church and state, even as they feel their progress hindered by the laws of the land. As vice president Mike Pence said in 2016: “I’m a Christian, a conservative, and a Republican, in that order.”

The synergy between Chinese Buddhist leaders (the most important of whom are represented by the Buddhist Association of China) and the United Front Work Department (the core agency founded in 1942 to manage relations with non-CCP elites) is somewhat different to what is happening in the US. There is no appetite to “make China Buddhist” in a Dominionist sense. Coming from an American perspective, Patrick Mendis nevertheless argues persuasively that Buddhism is China’s “soul power.”

He ties the Belt and Road Initiative with how Buddhism has related to China for the past two millennia: “Buddhism had always been an invisible attraction as Imperial China effectively integrated the Buddha’s dharma teachings with those of indigenous Taoist traditions and Confucian ethics. . . . the universal virtue of harmony, may help revive the concepts of equality and freedom inherent in the sutras of China’s Mahayana Buddhism, if Beijing wishes to pursue a new peaceful identity for a Pacific new world order.”

Meanwhile, former Indian ambassador and Asia watcher Phunchok Stobdan wrote in an excellent piece how the Buddhist Association of China has helped to promote “China as the chief patron of Buddhism at a global scale.” He notes: “Almost every prominent Buddhist institution in the world seems to have fallen into the BAC’s fold. The most prominent, the World Buddhist Sangha Council founded in Sri Lanka in 1966, is run directly by Chinese masters. . . . Buddhist globalisation and diplomacy, originally practiced by Indian emperors such as Ashoka and Kanishka, is now being lifted by the Chinese to embed into their soft power game.”

Across China and in Buddhistdoor Global’s home of Hong Kong, there have been multiple Belt and Road Initiative conferences and events hosted by (or having the involvement of) Buddhist leaders. The Chinese government’s discourse on global and domestic wellbeing (harmony, multiplicity, appreciation for diversity and complexity aligned with legitimate leadership) seems to be growing ever more closely aligned with the advice offered by the messengers and representatives of Dharma, particularly Mahayana Buddhism.

If the runes or oracle bones (take your pick) are being read correctly, then I think it’s safe to say that Beijing has thrown its spiritual lot in with Buddhism. And unless there are tectonic shifts in the balance of power between the Democratic Party and the Republicans, the GOP and its allies in the Supreme Court could slowly but surely shift America towards a configuration close to that envisioned by Dominionists. The stage seems to be set for not just a trade war, or even a military conflict. Peace—or war—could well be fuelled by religious preoccupations. There has never been a more important time to understand the religious spirit itself, in all its altruistic and malevolent human manifestations.