When I touched down this month in the airport of Dunhuang, a town with ancient roots stretching back to the opening of the first silk routes by Zhang Qian (200–114 BC), I saw a large placard that also appears at Leiyin Monastery, which is a short drive from the famous sightseeing spot of the Crescent Moon Lake. Built in 1986, Leiyin Monastery is a state-sanctioned institution that displays a speech on religion from Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

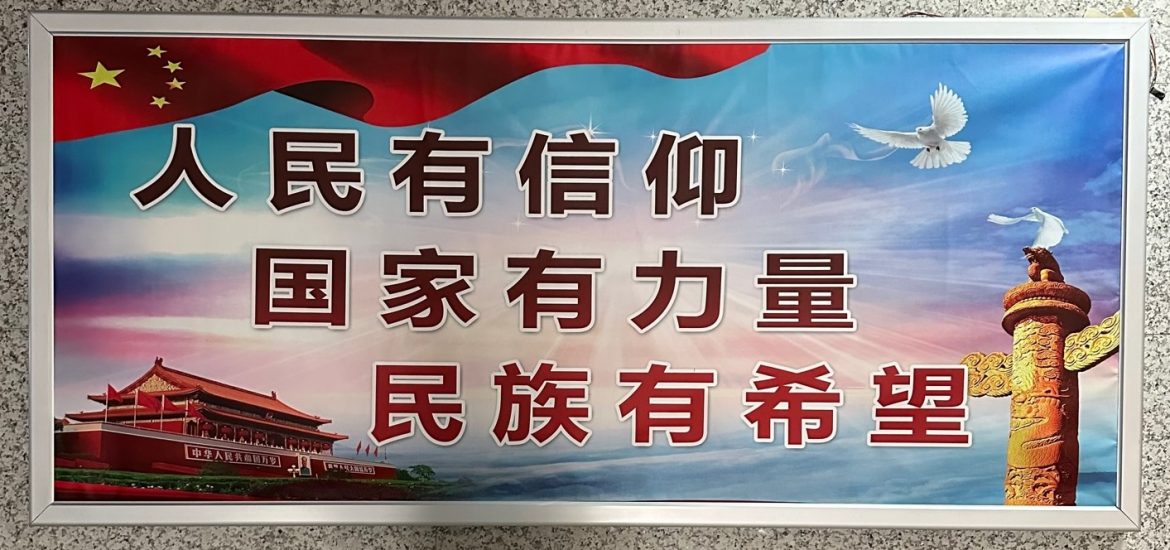

This placard displays a phrase I have not seen in Mainland China outside of Dunhuang. It seems especially devised for a location suffused with religious history and significance. It says:

When the people (renmin) have faith

The country (guojia) has strength

The nation (minzu) has hope

This is the Dunhuang airport version, with the Leiyin Monastery’s last two lines in swapped order.

Below this slogan at the Leiyin Monastery version are the ubiquitous twelve principles for president Xi’s Chinese Dream, with the first being “wealth and power” (fuqiang), a term pregnant with historical weight in the context of the Communist Party of China’s sense of history and patriotic mission of returning China to a central place in the world.

In many ways, Leiyin Monastery represents the way Buddhism has often lent support to state causes. In times of yore, especially under Amoghavajra (705–74) and his counsel to three successive Tang emperors, this was “imperial Buddhism” (Goble 2019, 175–80), an expression of esoteric Buddhism that supported and protected the interests of the Chinese dynasty. The original Leiyin Monastery, which was built in the Western Jin Dynasty (266–316), would certainly have borne witness to or participated in some form of imperial Buddhism. Those days are long gone, but the new words underpinning today’s Buddhist service for the state deserve attention.

This slogan in two places at Dunhuang distinguishes between three, theoretical, overarching institutions that the CPC serves in place of the long-gone Son of Heaven: renmin, minzu, and guojia. It is these political-sociological-philosophical constructs that the government now asks Buddhism to serve if it is to be accorded respect, deference, and influence by the Party.

But guojia and renmin are relatively common terms in nationalism. Why minzu? “Nation” seems to be a more appropriate translation than “ethnic group” despite the latter being closer in meaning. After all, China is a country of immense diversity. But the conscious use of minzu clearly indicates an attempt to conceptually make distinct “Chineseness.” It is similar to how Chinese writers of the imperial past equated the single civilisational polity of “zhongguo” with All Under Heaven (tianxia) with no one left out of China’s orbit.

For minzu, the new “tianxia,” to have hope and for the country to be strong, the people must have faith. This slogan indicates how a new kind of state Buddhism has emerged: not the imperial Buddhism of the Tang or other dynasties, but “the people’s Buddhism,” wherein the spiritual power of the sangha both strengthens and is strengthened by the material and spiritual well-being of the Chinese people. While in the past Buddhism might have offered to make individuals prosperous and powerful, now it extends that goal to an entire country.

The contemporary institutions of the Chinese sangha, which need to be registered with the Buddhist Association of China, are not really playing a new part. Buddhism could be said to be a revised civilizational role, and in a “nationalist” way is more expansive than even what imperial Buddhism once purported to do. Where one person, the emperor, once embodied the entire country (guojia), now over a billion people do (minzu), and it is Buddhism’s duty to lend faith to these constituents (renmin).

Reference

Goble, Godfrey C. 2019. Chinese Esoteric Buddhism: Amoghavajra, the Ruling Elite, and the Emergence of a New Tradition. New York: Columbia University Press.