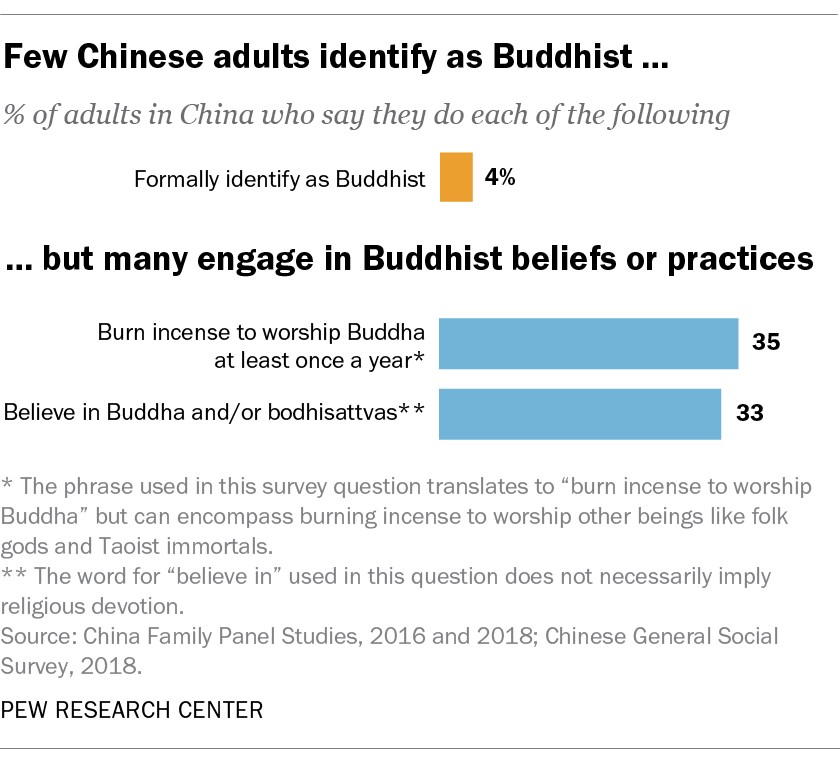

Last year, Pew Research Center conducted a survey of religious practice in China. Pew drew from the official Chinese General Social Survey from 2018, which observed that only 10 per cent of Chinese adults identified with any religion, with 4 per cent in turn (42 million people) formally identifying as Buddhist. Curiously, an older Pew Research survey from 2015 put the number of Buddhists at the time at 18 per cent—244 million! Clearly, the methodologies and parameters are not consistent.

Let us be conservative and prioritize the most recent survey’s statistics. If “formally identifying” means taking refuge in the three treasures under a qualified master (and possibly undertaking the Five Lay Vows), then it would indicate that only a small number of Chinese people have gone through the ritual ceremony that officially makes one a “confessing” Buddhist.

This actually is not a huge surprise. While taking refuge is a common practice in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asian nations (in fact, families will renew their refuge taking at many different ceremonies, including those over the vassa period like Kathina), the very same act has always been seen in a culturally different light by Chinese throughout history. While the act of taking refuge in and of itself was never something extraordinary, its revival in the post-Mao period has made taking refuge a specific rite of social demarcation among Buddhist believers. Gareth Fisher puts it thus:

Like lay Buddhists in early times, many (but not all) of these lay Buddhists have formally taken the refuges and obtained conversion certificates (guiyi zheng) that formalize their status as laypersons . . . they self-consciously take on a specific social identity, that of a follower of Buddhism or disciple of the Buddha, that others in society do not. . . . choosing to formally become a jushi, fo dizi, or fojiao tu is a mark of personal pride and, at least among themselves, a means of establishing moral superiority.

(Fisher 2015, 14)

But perhaps there is something in the reverence, even socio-cultural value, accorded by the Chinese to the Buddhist layperson’s identity. Nyanaponika Thera, one of the 20th century’s greatest German-born monks, meditators, and translators, wrote a marvelous essay about the significance of taking refuge, which I cannot do justice comprehensively here. But consider this moving passage:

In accepting the Triple Gem as his guiding ideal the disciple pledges himself to subordinate gradually all the essential activities of his life to the ideals embodied in the Triple Gem. He vows to give all his strength to the task of impressing this sacred threefold seal upon his personal life and upon his environment too, as far as he is able to overcome its resistance. The threefold refuge in its aspect as the guiding ideal, or as the determining factor of life, calls for complete dedication in the sphere of external activities.

(Access to Insight)

In other words, in China, the act of refuge taking is accorded great importance, since the ceremony also has social weight. But let us revisit the 2023 Pew report. A full third of Chinese adults, 17 per cent, believe in the idea of the Buddha and the bodhisattvas. But social misconceptions and attitudes about Buddhism might hinder conversion proper: for example, some people might believe only monks or nuns have the right to call themselves Buddhist. When I first took refuge in Buddhism in 2008, some of my friends asked me if I had to be celibate. This conflation of religious affiliation with monasticism is not uncommon.

Others might feel that Buddhism does not require formal adherence because of China’s historical and ongoing intertwining of folk religion, Confucianism, and Daoism with Buddhism.

Buddhism, especially Mahayana Buddhism, has created two thousand years of Buddhists of “simple faith.” These are practicing Buddhists who might not be well-versed in philosophy or ritual, but pray and meditate, support monasteries, visit temples and pagodas, and truly sustain the sangha in the world. China has “incubated” Buddhism longer than most countries in Asia, while at the same time elevating the act of refuge taking to a public statement or declaration about one’s place in society. There are therefore many “non-Buddhists” and formal Buddhists that contribute to the Dharma as China’s enduring cultural and spiritual fabric.

In this sense, a faith tradition’s numbers do not matter—or at least, should be outranked in priority by vibrancy.

Reference

Gareth Fisher. 2015. From Comrades to Bodhisattvas: Moral Dimensions of Lay Buddhist Practice in Contemporary China. Hong Kong: HKU Press.

See more

6 facts about Buddhism in China (Pew Research Center)

Buddhists (Pew Research Center)

The Threefold Refuge (Access to Insight)

Related blog posts from BDG

The Buddhist cultural complex across Asia: Virtues make a religious person

President Xi’s visit to Hongjue Temple was for American and Gelug eyes