Archaeology is the material study of the ancient past. Although it involves ancient ruins, long-forgotten remains, and long-faded things, it is actually a rapidly evolving field. Archaeologists in popular imagination and culture stylishly swagger their way into ancient sites with nothing more than a map (think Tomb Raider or Indiana Jones). But work-smart-not-hard specialists in 2023 would probably be more at home with deploying a scanner to digitally construct the entire place on a tablet and computer system, before sending in another advanced drone – be it underground, underwater, or airborne – to surgically document a target at the site.

In other words, archaeologists are at the forefront of incorporating the latest in digital advancements such as VR (virtual reality) and AR (augmented reality), mapping and scanning, and drone deployment. In this sense, they serve as the vanguard of discovery while historians “form up the rear,” contextualizing the discoveries in a broader narrative and situating them in a long institutional memory that helps humanity to understand itself.

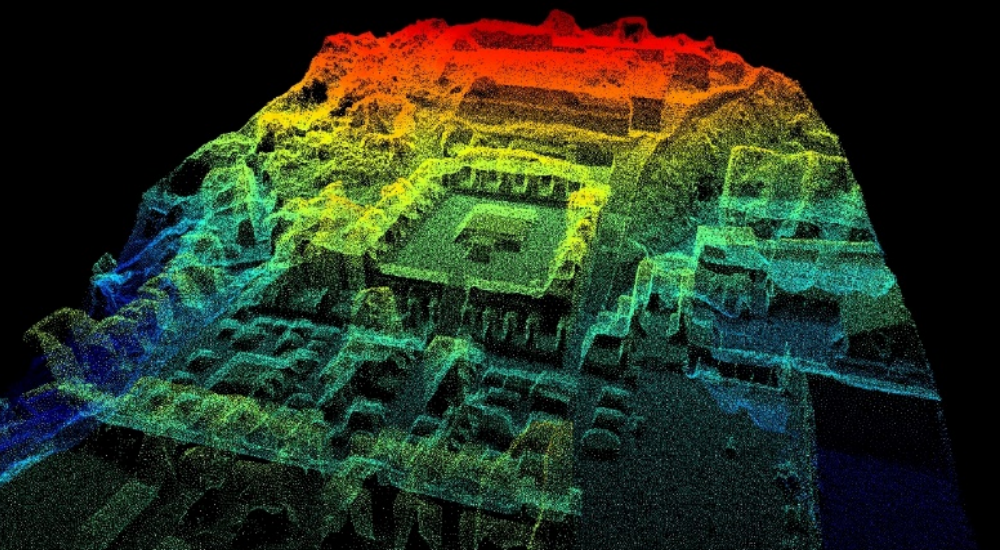

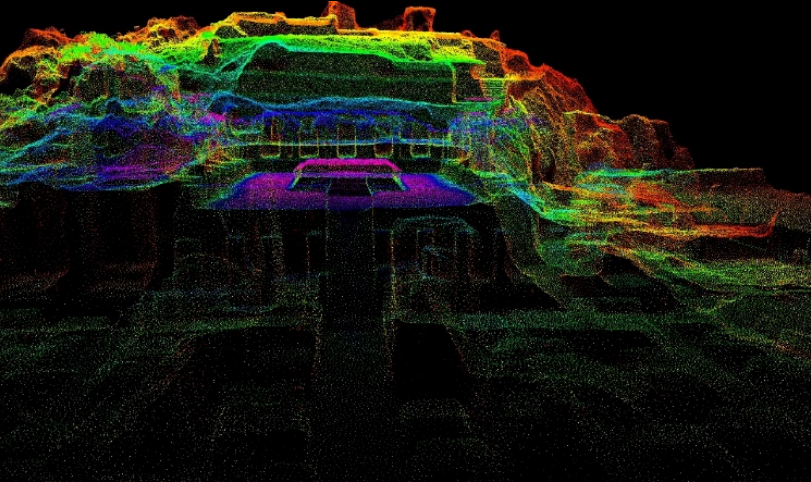

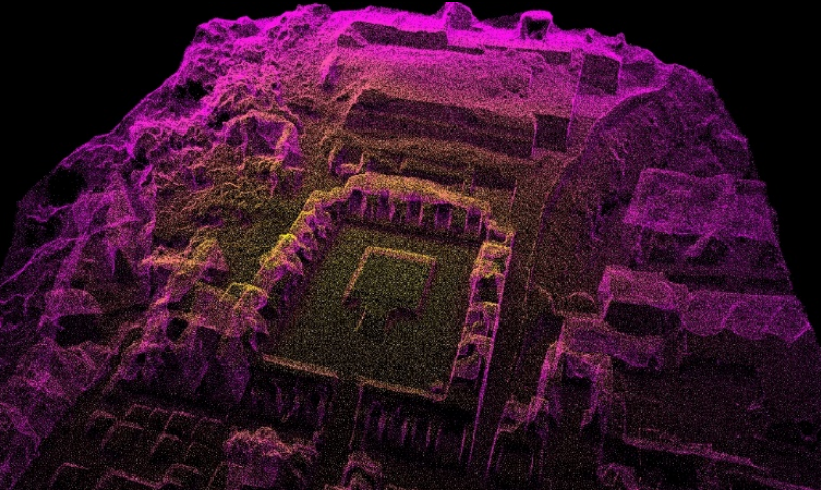

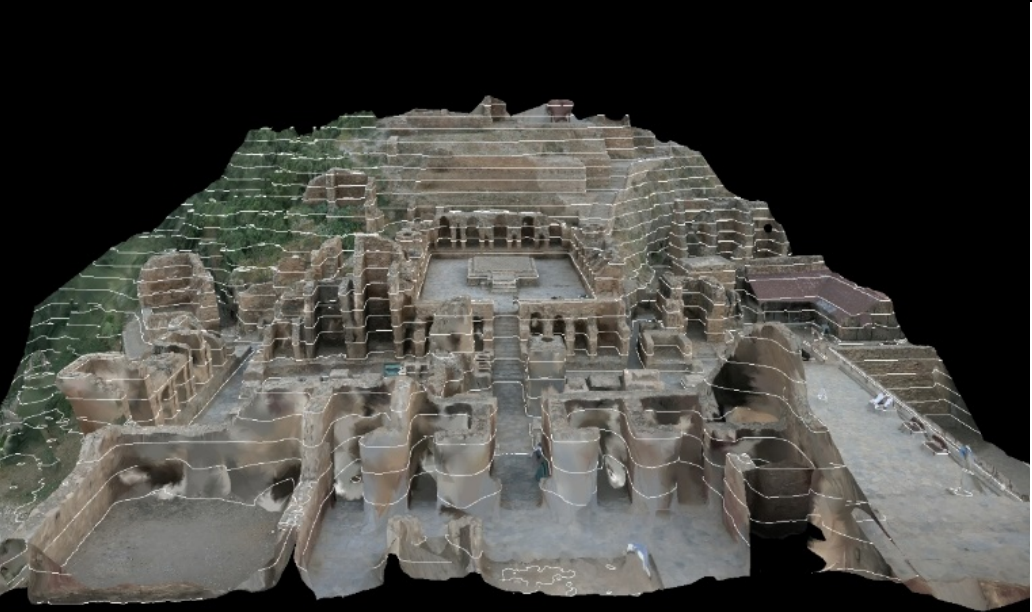

When seen this way, it seems logical to conclude that 3D terrestrial laser scanning is the frontier of Buddhist Studies. This is because it combines the very newest in scanning with the most reliable kind of historical evidence: physical monumenta and epigraphic evidence. There are few better case studies than what the Digital Heritage Center at KPDOAM, is doing at Takht-i-Bahi. According to the Center in a report titled Digital Reconstruction of Takht-i-Bahi site, KPDOAM is deploying the FARO® Laser Scanner, a high-speed, 3D laser scanner for detailed measurement and documentation. As indicated by the name, it deploys laser technology to rapidly produce detailed 3D images of complex environments and geometries. Using scanning parameter settings, FARO can assemble images from millions of 3D measurement points. Their specs are impressive, as are their prices – a typical model will cost at least US $30,000. The model the Digital Heritage Center’s team is using is the 3D Terrestrial Laser scanner FARO Focus S150 (Serial Number: LLS081812358).

Included in the FARO inventory are six spheres and three checkerboard targets to comprehensively scan the whole site. As the report notes:

Site survey

Based on the site visit and the obtained site plan (if available) or using Google Maps/street view plan to determine the estimated number of scan points that will be taken for scheduling.

Scan point planning

After determining the number of scan points, plan out the scan point route and registration method used for the project. The general method uses a sphere target for a continuous route and a checkerboard target for a branching route and as a safe location in case of finishing up for the day or being forced to stop the scanning process due to various factors (bad weather, depleted batteries, etc.)(KPDOAM)

Scanning processes

For building scanning, this is only a rule of thumb for general planning where actual site execution conditions and consideration of building detail shall require to be taken into account. Commonly, actual site execution shall be using a mix of this range for the internal of the building. As for the external building, the building façade shall be kept at a distance of 10-20m apart to maximize both good coverage and avoid unnecessary duplicated small detail. Multiple scan locations shall be placed at selected locations appropriately to observe a complete building, i.e., inside and outside of a building.

The methodology deployed by KPDOAM is “H-BIM,” or Historical Building Information Modelling. The building model development during a facility’s lifecycle consists of five stages, LOD 100 to 500. Using a FARO model to scan to BIM offers many benefits, from more accurate visualization of the building in question to more rigorously analyzed information. As the report outlines, FARO is moving through these five stages: conceptual design, design development, construction documentation plus presentation and bidding, construction, and as-built modelling.

Pushing further ahead into the future are VR and AR considerations. VR is purely artificial and immerses one in an entirely different world altogether. Most conservation centers are far from that prospect – to be able to map out a site like Takht-i-Bahi and replicate it in a program for users to explore and study from the comfort of their homes. Nevertheless, KPDOAM is preparing a pilot project that will eventually result in a digital reconstruction of Takht-i-Bahi, accessible through a VR application. “The results obtained from this pilot will help to improve the effectiveness of the promotion and conservation effort of the historic sites and monuments.” (KPDOAM)

Augmented reality, meanwhile, has already become a reality at many conservation centers. From the Dunhuang Research Academy to the Archaeological Survey of India, AR integrates digital information with the user’s environment in real-time. In Dunhuang in 2013, I distinctly recall walking into a replica of one of the Mogao caves, which was only possible due to a highly accurate computer model that had scanned the cut rock, floor, ceiling, and murals and sculptures within. Yet it was also an installation that was pushing the limits of digital interactivity, going beyond scanning QR codes with smartphones and offering sound and light when certain areas and triggers were activated. “AR users experience a real-world environment with generated perceptual information overlaid on top of it,” notes KPDOAM’s report. “By exploring AR, the project team’s expectation will be focused on revisiting the actual site and exploring the digital reconstruction output. By doing so, we will enable us to extend the digital reconstruction output as a benchmark to further improve the accuracy of our narrative and understanding of our tangible and intangible heritage.”

The sites of Takht-i-Bahi and Kafir Kot are KPDOAM’s pilot projects, and once done successfully, the team will extend the FARO-BIM model to other archaeological sites. With the progress already made on Takht-i-Bahi, this ancient site of Buddhist practice and devotion will serve as a model for all of Pakistan’s Buddhist sites, sculptures, and murals, leading to their eventual total digitization and replication in VR or AR. This is a brave new world for Buddhists as well as secular conservators and archaeologists, and questions inevitably arise as to the fate of the original sites or artifacts. This is the perennial question, and the answer will determine the stakes of the entire enterprise. As with all technological progress, we must ask ourselves in good faith if we are advancing for the right reasons, and what we intend to do with such information and power.

This article was written in collaboration with the Digital Heritage Center of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPDOAM)