In two years, Hong Kong has enjoyed two special exhibitions centred on Yuanming yuan, the Garden of Eternal Brightness. Located at Haidian District in modern Beijing, this was a vast, palatial complex of residences and retreats enjoyed by the Qing dynasty’s (1644–1911) imperial household for 136 years. One exhibition was done last year at Indra and Harry Banga Gallery at City University. It was significant for its centerpieces of four of the original bronze animal heads of Haiyantang, the famous fountain at the European mansions or Xiyang lou (which, beautiful as it is, only comprised two per cent of the whole Yuanming yuan).

The second is a temporary exhibit at the Hong Kong Palace Museum. On 20 March, it formally opened “Yuan Ming Yuan – Art and Culture of an Imperial Garden-Palace.” It runs until 12 August, is supported by The Hong Kong Jockey Club, and was co-organized with the Palace Museum and the Yuanmingyuan Administration Office of Haidian District of Beijing. Curiously, in all its other media, the exhibit spells it as “Yuanming yuan.”

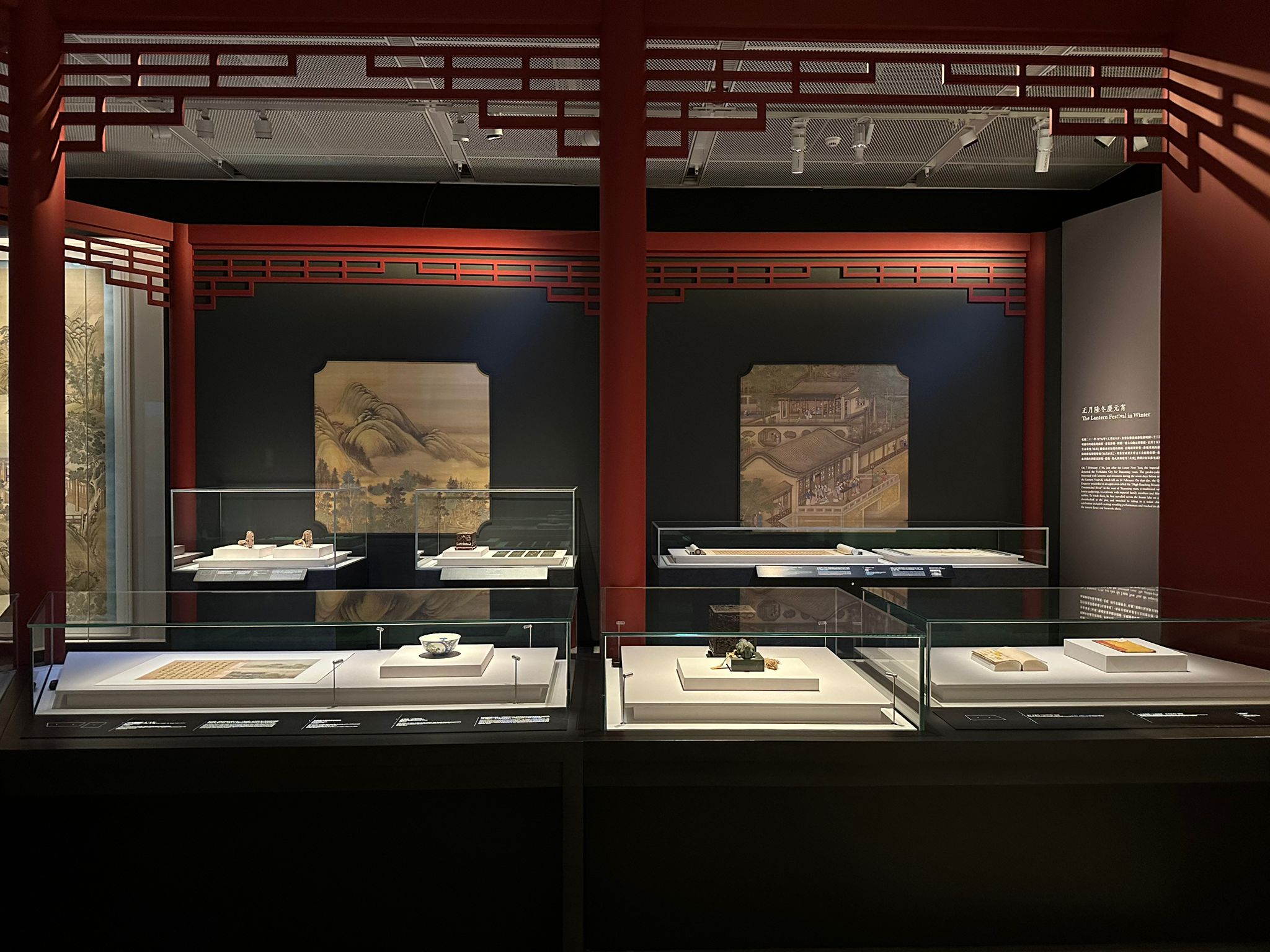

I went to the exhibit a few days after the opening: as usual with the Hong Kong Palace Museum, its curatorial sense of space, aesthetics, and museology is estimable. The 190 artifacts, architectural models, and paintings showcased feature calligraphic recounts of festivals written by the Qing emperors, ritual items used by Qing nobles and their retainers, and much more.

Several digital animations, one of which tells the timeline of Yuanming yuan’s construction, and with three screens displaying HD drone camerawork of its ruins at the end of the exhibit, are particularly vivid and impressive. One of the most beautiful shots is of the ruins of the Hall of Universal Peace (萬方安和), which was built in the shape of a Buddhist swastika (卍). One of the display items is a gorgeous model or restoration plan of the Hall, made during the Tongzhi reign (1873–74) at the Imperial Architecture Studio. The accompaniment to the Hall’s model, complete with embankments, culverts, rooms, and interior decorations, explains that it stood in a scenic lake and would have been accessible for the emperor’s boat via a southern pier or by land via bridges to the east and north.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the Hall of Universal Peace, replete with Buddhist symbolism and Dharmic power, was the residence of the Yongzheng Emperor (1678–1735), who saw himself as enforcing a Buddhist universal peace to win the hearts of all people. His aspiration was also expressed in his seals, which were commonly used by Qing emperors. Personal seals were not only for stamping the ruler’s imprimatur on official documents, but were used to communicate personal taste, express sobriquets like pen names and courtesy names, and mark their presence on pieces of art or calligraphy.

The imperial house of Aisin Gioro saw itself as the ruler of a multi-ethnic, multicultural empire, and as such, they not only retained the shamanic rituals and beliefs of their Tungusic homeland of Manchuria, but also absorbed Tibetan Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism. As the Manchus came to see China as their primary dynastic holding, they seem to have resolved to become more Confucian than the native Confucians.

But it’s complex. As a prince, Yinzhen, the future Yongzheng Emperor, was a pious Buddhist and ardent student of Vajrayana and Chan teaching. He evidently went through a bit of a “new convert” phase, having used two seals with the characters, “Buddhist layman of perfect brightness” (圓明居士) and “Buddhist layman who clears away dust” (破塵居士). The latter seal is on display at this exhibit, and it hearkens back to the 8th–13th century Chan scripture of the Platform Sutra, in which the Sixth Patriarch Huineng utters the verse:

The mind is the Bodhi tree,

The body is the mirror stand.

The mirror is originally clean and pure;

Where can it be stained by dust?

The context of this verse is when Huineng and Shenxiu offer differing perspectives on the nature of enlightenment. Shenxiu, a learned and senior monk, is opposed to the perspective of Huineng, famously uneducated and illiterate. The former says that in contrast to Huineng’s understanding of “sudden enlightenment” (satori in Japanese Zen), “gradual enlightenment” is the way to go, with the body like the bodhi tree, and the mind a clear mirror. “At all times we must strive to polish it, and must not let the dust collect,” said Shenxiu.

I am fascinated by the implication that through his sobriquet of “Buddhist layman who clears away dust,” the Yongzheng Emperor seems to have favored Shenxiu’s idea of gradual enlightenment. There is no way someone of his erudition and intellectual penetration would have misunderstood the Platform Sutra, which favors Huineng’s sudden enlightenment, so completely. I can only conclude that he had positive sentiments about the hard work (or in Buddhist lingo, “self-power”) that must accompany the path of gradual enlightenment. It would suit his reputation for long hours at work and austere personality. He was the Qing-era equivalent of a grinder: just like with statecraft and ruling China, he might have seen spiritual cultivation as a matter of consistency, discipline, and rigor.

Or, perhaps, the emperor is being more innovative than we think. Perhaps his sobriquet is a boast. He isn’t clearing away dust, but has already accomplished it. He has seen what Huineng urged us all to see. How can his mirror possibly be stained to begin with?

Related blog posts from BDG

Yongzheng’s Yuanmingyuan: The Dharma Dimensions of the Old Summer Palace