The grottoes of Mogao and Yulin are already fairly remote places, far into the northwest deserts of China. But one “wilder” place to find unique Buddhist cave art is located at in Sunan Augur Autonomous County, Zhangye in Gansu Province. This is a scenic, mountainous region that has been populated by Buddhist caves since medieval times. I visited this far-flung place during my visit to sites along the Chinese Buddhist Silk Road. It is spiritually anchored by a temple to Manjushri, where there is an active Vajrayana community.

The caves are located on the expansive cliffs of the front and back faces of the mountains. Walking to each one was moderately taxing for me, though I am sure a hiker would traverse the permitted range easily. There are sandy structures made of stone, both small and large, that would have housed the monastic community on retreat up here. The earliest caves were excavated during the Northern Liang (397-439) period, around the middle of the fourth century AD, a period close to when the Tiantishan Grottoes in Wuwei began to be dug out. The caves open to the public are small, cramped, and were heavily vandalized by ignorant or malevolent people, or both, over the centuries.

They primarily have a dome-shaped ceiling with square-shaped central pagodas that also function as a column. The central columns are divided into three sections from top to bottom, with the lower layer being a square platform base. Each side of the upper two layers is chiseled with a round arch niche. A Buddha statue sits inside the niche, with two bodhisattvas flanking. The cave paintings exhibit common themes and motifs, like apsaras (feitian), bodhisattvas like Samantabhadra, and donors. The Buddhas that sit in the centre of every side in each cave have all been damaged, their heads looted.

It is uncertain how the mountain area came to be associated with a cult of Manjushri. We know that each year, from the first day to the eighth day of the fourth lunar month, devotees and tourists come from the surrounding areas in Gansu to see both Buddhist and Daoist activities being held at the sites nearby. So today there might be an eclectic, interfaith presence in the region. But according to folklore handed down the generations in this community, Manjushri seems to have appeared to the 3rd Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588) in the area, meaning that Sonam Gyatso made this place a focal point of Vajrayana practice.

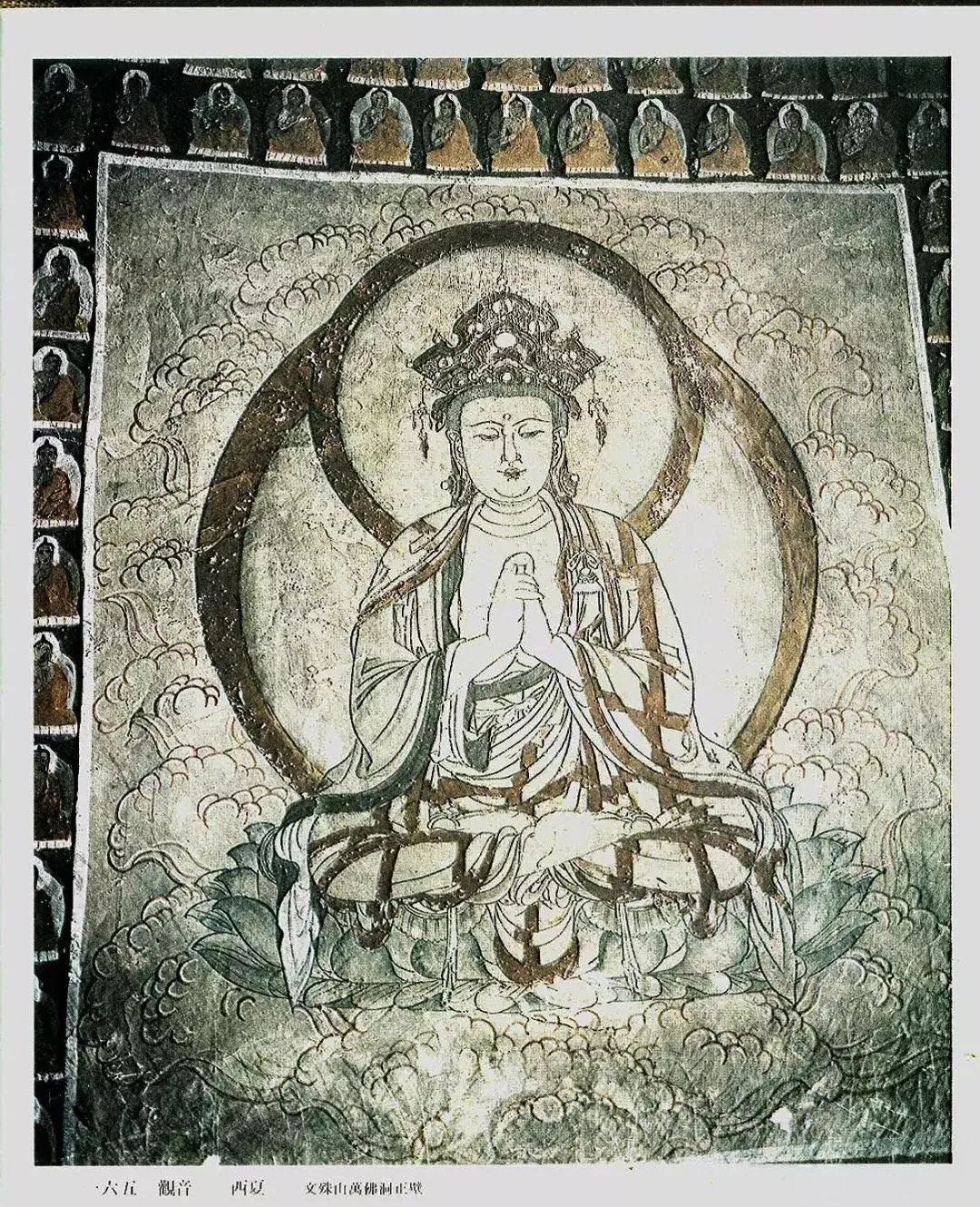

Despite being host to 131 surviving caves, there are only 4 caves open to the public. The one that was most important to me was the Ten Thousand Grottoes, which was first established in the Northern Wei dynasty (386–535). But this cave, along with several others, contains some of the most precious surviving heritage of the Western Xia (1038–1226), including a mural of Vairocana, the esoteric head Buddha of both Chinese and Tibetan tantric Buddhism, on the eastern wall. In these public caves, it seems that the Tanguts came into these sanctuaries and re-consecrated them as tantric anchors. Vairocana is drawn beautifully, complete with the sumptuous frock of a monastic teacher and his signature mudra of the Avatamsaka Sutra (Huayan jing).

The Ten Thousand Grottoes also has a large-scale painting of the Maitreya Sutra (mile shangsheng jingbian 弥勒上生经变), which was also drawn meticulously and painstakingly by a Tangut painter (or team of artists). This not only a painting of a bodhisattva, like of Samantabhadra and Maitreya at Cave 3 at the Yulin Grottoes. This is one of the few Western Xia murals preserved in China. The garments and expressions of the figures are exquisite, painted in a manner that is completely distinct from the Northern Wei, Tang, and Yuan styles at Mogao. Maitreya, the central figure, also seems to be doing something fascinating: he appears to be visualising or invoking multiple Buddhas. Maitreya is also garbed in Tibetan attire, indicating that Vajrayana had penetrated into the region and integrated into local belief by the time the Tanguts were around.

We do not know why there is such a rich repository of Western Xia (Tangut; Xixia) art here. We might have to admit that they might simply have been part of the long line of dynasties that have patronised Buddhist caves. It is extraordinary enough that Manjushri Mountain’s exquisite Xixia murals are distinct from the more famous ones found at Yulin. These caves are therefore priceless foci for the study of Western Xia.

Before my visit, I could find only a few websites discussing the caves in Chinese, and essentially no English-language of material. The Manjushri Mountain Grottoes do not come under the jurisdiction of the Dunhuang Academy, and unlike many other grotto regions, seem to have enjoyed little to no attention in the Anglophone press or scholarly world. Standing tall and lofty in the heart of Gansu, the caves of Manjushri Mountain are precious sources for the study of Buddhist art from the Northern Liang and Northern Wei all the way up to the Western Xia and Yuan. No doubt further research will help to connect the dots between the Buddhist architecture of the Hexi Corridor, the mysterious Tanguts, and the medieval happenings that defined these regions, which were geographically peripheral to central China, but critical to the Chinese Buddhist story.

Related blog posts from BDG

From the Capitals to the Corridor: A Visit to China’s Silk Road

Vairocana: The Esoteric Sun Buddha along the Chinese Buddhist Silk Road