Enjoyers of Romance of the Three Kingdoms would know about the rich history of Suzhou. Jiangsu’s capital, which is celebrated as one of China’s most culturally rich cities, has a proud past. It was part of two states called “Wu,” the first being the Kingdom of Wu (12th century BC–473 BC) that warred with other fiefdoms during the twilight of the Zhou Dynasty. There is also the more famous Eastern Wu (222–280 AD) of the Three Kingdoms period that was ruled by the Sun clan and waged war against Shu Han and Cao Wei.

Only after Wu fell to Cao Wei’s successor state, Jin, was China reunited once again after a period of civil war that would be immortalized and re-interpreted in TV series, comics, and video games that have become pop culture icons and historical memes.

I came away from my visit engrossed in the idea that Suzhou, far from being at the periphery of medieval metropolitan Buddhist centers like Chang’an and Luoyang, witnessed a cross-pollination of esotericism and Chan that has yet to be seriously documented.

The Suzhou Museum, designed by Suzhou-born architectural icon I.M. Pei, holds replicas of priceless Buddhist artifacts that were discovered at various sites across the city. Only by visiting the museum did I find out that Sun Quan of Eastern Wu built Puji Temple, now known as Ruiguang Temple, for the monastic Xingkang of Kangju. Although the temple has a history dating back to 241 AD, six years later in 247 a pagoda was built in the complex, from which a trove of precious items was unearthed in 1978.

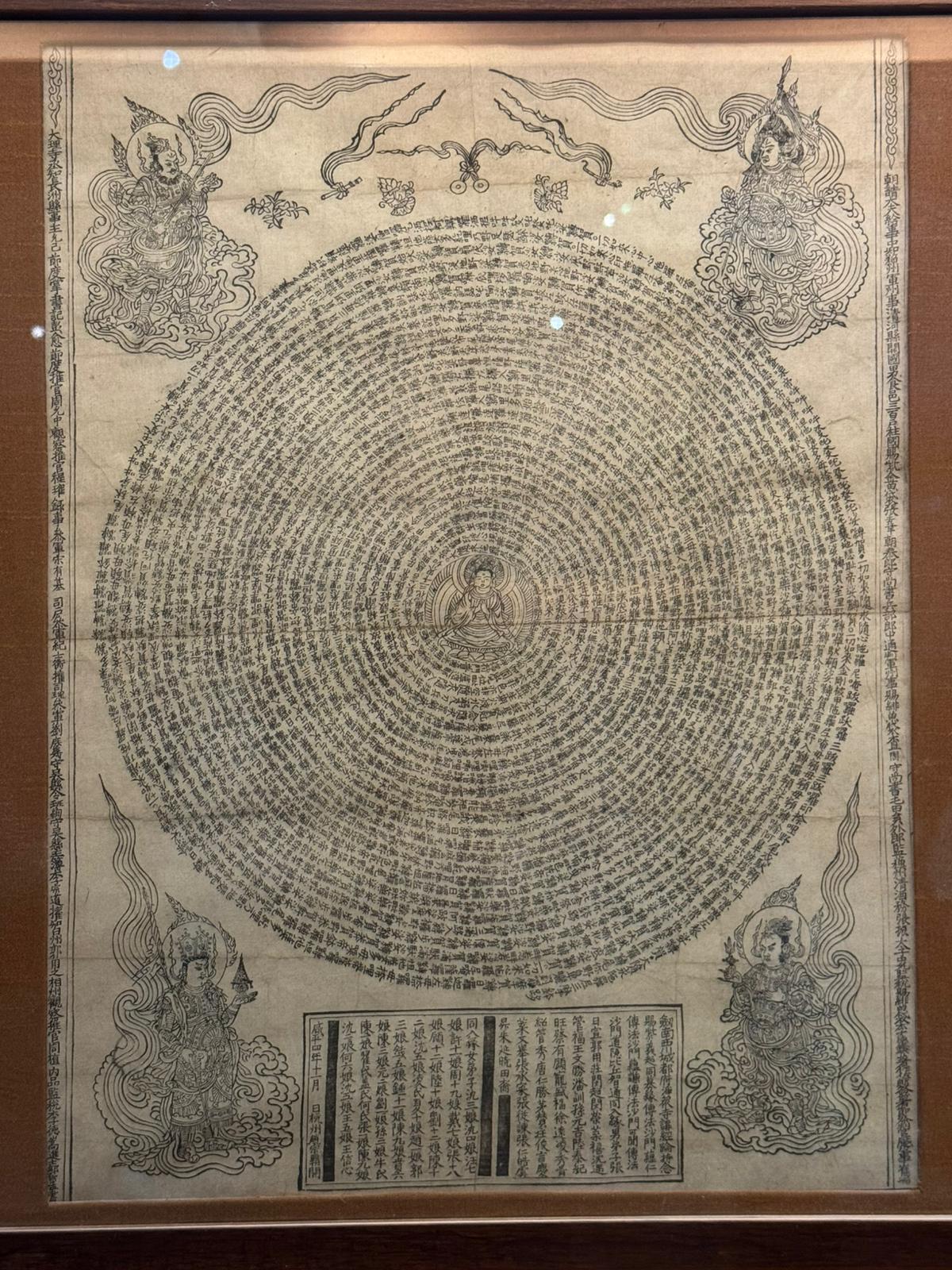

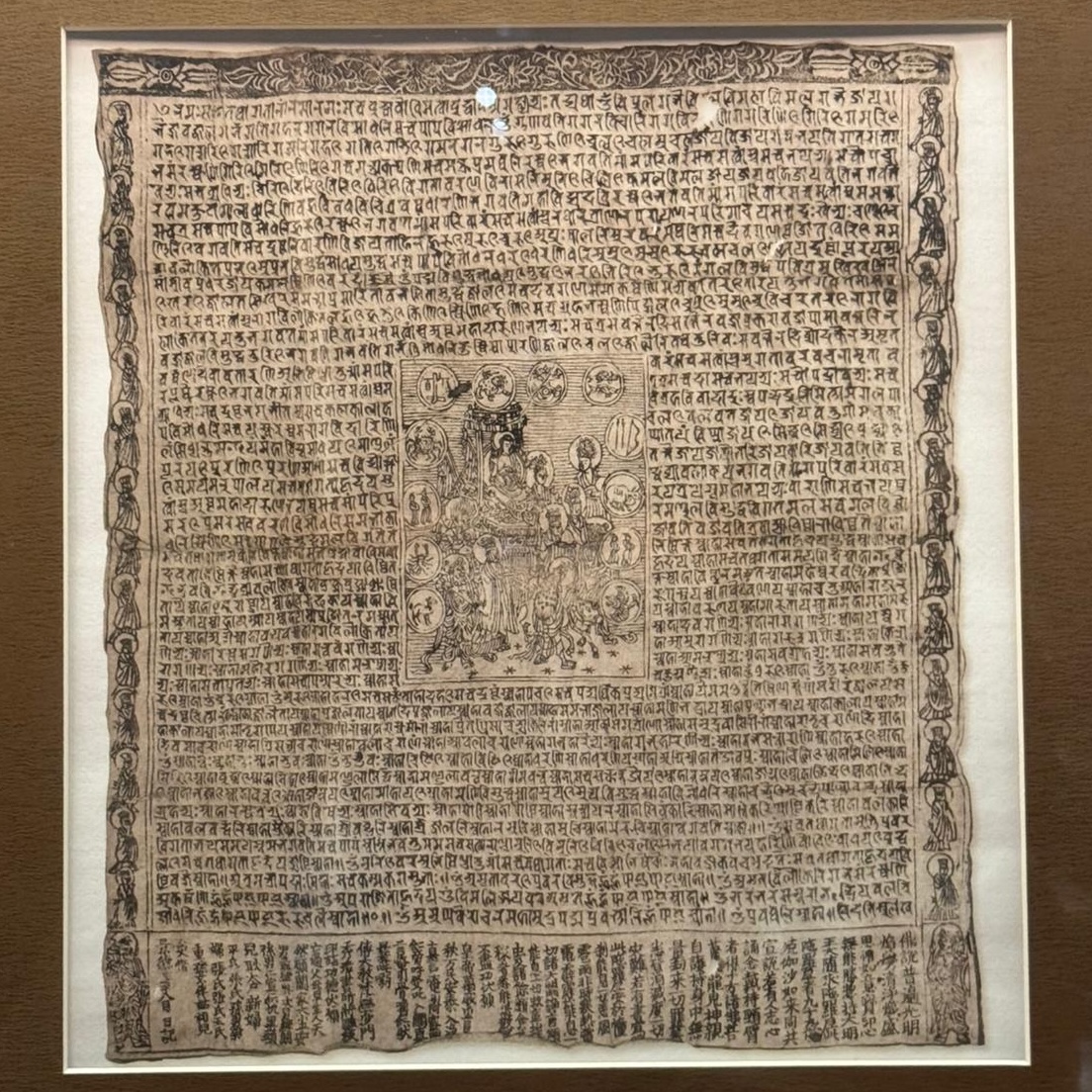

Dating to the Tang and Song dynasties, my favorite items relate to Chinese esoteric Buddhism, such as a Sutra Mantra of Qiudharani in Sanskrit, Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127 AD) written in Buddhism’s gorgeous Indic script and tantalizingly revealing its owner and affiliation: Sramana (monastic) Xiuzhang of the Great Teaching of the Study of Dharani. There is another Sutra Mantra of Qiudharani in Chinese, Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127 AD), which is devoted to the cosmic esoteric Buddha Vairocana (Great Sun Buddha), with the dharani’s Chinese characters radiating exquisitely from the central figure like rays of the sun.

The most iconic traditional structure in Suzhou is the Huqiu Pagoda, which is part of Yunyan Temple at the top of Suzhou’s Tiger Hill (hu means “tiger” in Chinese). Built between 959–61 AD, another storehouse of incredible artifacts was discovered, including a Song-era image of Avalokiteshvara with 11 faces – which usually indicates an esoteric provenance. 11-Headed Avalokiteshvara appears in the Dhāraṇī of Avalokiteśvara Ekadaśamukha Sūtra, a dharani sutra (a scripture which contains a recitation, or magical incantation), that became popular in China. And this esoteric expression of 11-Headed Avalokiteshvara has long been popular in tantric regions west of China, like Oddiyana and Kashmir.

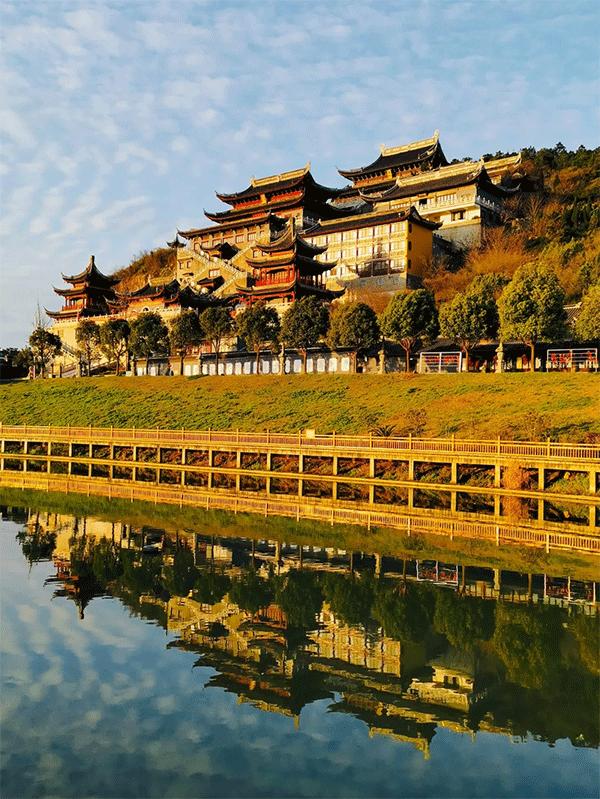

Speaking of this bodhisattva, I paid respects to the Lord of Compassion two times on my trip. The first was at Chongyuan Temple, where across from the main temple complex is a “Lotus World” that houses a 108-foot-tall statue of Guanyin, apparently carved from a single boxwood tree. The second was at the White Crane Temple, also known as Baihesi, which is a sumptuous, beautiful complex seemingly folded into the mountainside.*There is very little known about this temple except the fact that it was apparently established during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), but the fact that there is a replica cave devoted to Bodhidharma, complete with statue, suggests that there must have been some connection to (or some memory of) Chan Buddhism.

The fact that there is an image of the fabled inventor of Shaolin martial arts, while the temple is named “White Crane,” seems too tantalizing of a potential connection. Tibetan White Crane is part of the tsalung or Tibetan chi gong system. Was there someone who would have known of Bodhidharma and Shaolin – or, perhaps, the tsalung of Tibet – in Suzhou?

Which brings us back full circle to the earliest documented accounts of Puji Temple, and Sun Quan’s welcome for Xingkang of Kangju. Who really was Xingkang, a monk whose name is completely unfamiliar and is otherwise unmentioned in the sources we have about the Three Kingdoms? Kangju (康居) was a land to the west that was likely Sogdiana. Xingkang could could also have been from Tianzhu, the traditional Chinese name for the Indian subcontinent. A mural in Cave 323 of the Mogao Caves, Dunhuang, explain his story visually:

He was promoting Buddhism mainly in the Jiangnan (region south of the Yangtze River) and was of great significance in the history of Buddhism being spread to China’s south. During the Three Kingdoms Period, Buddhism was not yet popular in the Jiangnan region. In 241 A.D. (the fourth year of Chiwu of the Wu State), he traveled from Luoyang to Jianye (today’s Nanjing), the capital of Wu at the time. Due to his strange appearance and clothes, he was received by Sun Quan, the Emperor of Wu. Kang told Sun Quan that the magic power of Buddhism was boundless, and he offered to present the emperor with a Buddhist relic within 21 days. When the Buddhist relic was presented, it emitted a light of five colors. Watched by an audience of subjects and ministers, some even hammered the Buddhist relic that caused no damage at all, Sun Quan admired it so much that he had the Jianchu Temple built for the monk, the first Buddhist temple in Jiangnan, which laid the foundation for the spread of Buddhism in the region.

(Dunhuang Academy)

Although there is little fire, there seems to be a good deal of smoke. There is a connection between Suzhou Buddhism and non-Chinese strains of Dharma transmission that scholars have barely begun to explore. Master Xingkang brought to Luoyang and then Jiangnan a form of miracle-making Buddhism from the western regions that seemed to be in constant contact with the trends of esoterism and eventually, full-blown tantrism. This expression of Buddhism, barely recorded yet scattered in hints and fragments across Suzhou’s archeological materials, would have encountered and mixed with the Chan Buddhism that was being transmitted down south from Shaolin, down the lineages of Bodhidharma and other Chinese masters.

How might esoteric Buddhism from the Tang era onwards have influenced Suzhou culture, literature, and spiritual practice? Is there some hidden tradition of martial arts in the coded heritage of a White Crane temple with a Bodhidharma meditating within?

All questions from one short sojourn in Suzhou.

* One of its most endearing oddities is that at one of the upper levels is a very comfortable library-like facility with spaces for meditation and copying scriptures, as well as an extensive library of sutra editions as well as contemporary books.

See more

Mogao Cave 323 (Early Tang Dynasty)

Related features from BDG

Echoes of the White Crane: Laurence Brahm’s Tale of Martial Arts as Kinetic Meditation