“In the absence of any government restrictions, China’s Gods have become a lively trade article.”

Friedrich Perzynski, Hunt for the Gods (1913)

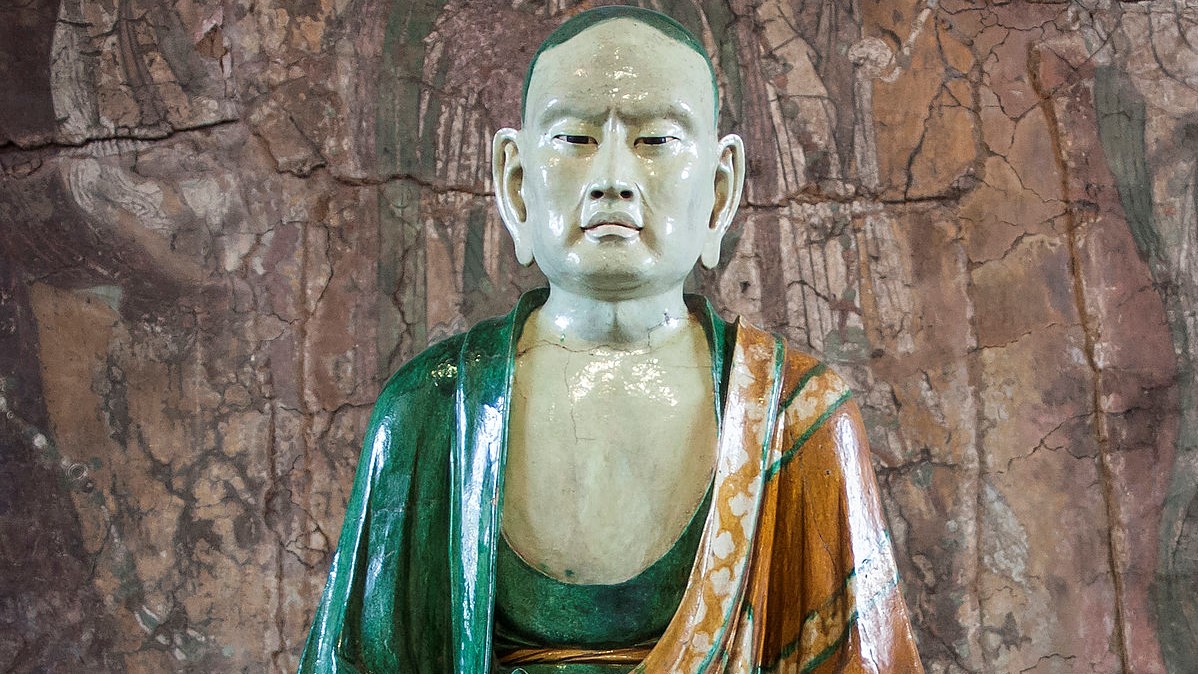

In the early days of the Republic of China, a unique group of sixteen Buddhist sculptures called the “Yixian Luohans” (luohan means arahat in Chinese) appeared on the embryonic market of Chinese art. The book’s author is Tony Miller, a long-time public servant and current resident of Hong Kong. A collector of Buddhist art, he has spent the last ten years researching the Yixian Luohans, and the result is his tour de force of a book, with a narrative that presents an exciting, yet tumultuous and chaotic era. For Sinophiles and art dealers, the early Republican decades meant working with competitors in the same field or forming unusual connections to access once-inaccessible religious sites. At points the book felt like a cross between Uncharted and Indiana Jones.

By China’s embryonic art market, I mean a chaotic free-for-all that was driven by calculated deception and quick thinking as much as scholarship and fine taste. In this “Wild West (East?)” of smuggling, auctioneering, and loot, a diverse range of charismatic and complex individuals scrambled to sell the Yixian Luohans. The first two Luohans were unveiled at the Musée Cernuschi in June 1913 and ten surviving sculptures reside in some of the most famous museums in the world: in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Sezon Museum of Modern Art in Karuizawa, the Musée Guimet in Paris, the British Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, the Penn Museum in Philadelphia, and the Royal Ontario Museum. Central to the mystique of these statues is not only their uncertain provenance, but also the consciously created myth that they were hidden in inaccessible caves southwest of Beijing, away from the eyes of barbarian invaders. Miller seeks not only to debunk this myth, but also Miller provide his own estimates of their provenance by the conclusion of his book.

One of Miller’s core protagonists is Friedrich Perzynski (1877–1965), who was among the first Europeans to discover the Yixian Luohans. The intricacy and provenance of the luohans are worth several volumes of studies and books. He quickly discovered that Through many twists and turns experienced by acquirers of Buddhist art like Perzynski and contemporaries George Crofts, C.T. Loo, and Terasawa Shikanosuke, Miller identifies a consistent trend that characterized the nature of the Chinese art market: “the eventual pattern of sales suggests an unusual degree of orchestration, and that reflects the unique commercial challenge faced by the dealer, or dealers, who discovered the damaged statues and persuaded the temple to relinquish them for sale. Nothing like them had been seen before in the West. The statues were obviously rare and, but for the damage, would immediately have qualified as museum quality. That would have limited the market. . . . Would there be a market for sancai (三彩) sculpture? Certainly not in China; save possibly a wealthy expatriate. What about Europe?” (151)

The luohans were certainly beautiful in the sellers’ eyes, but there was no guarantee that they would sell well. What followed was a conscious effort to market and transport the statues into whichever hands that were outstretched. Miller writes: “Would there be a market for so many at the same time? The dealer(s) had to de-risk the transaction by working closely with competitors to exploit their collective international connections. It helped that most of them knew one another.” (151)

The book is divided into six chapters that charts, chronologically, how the statues began their journey around the world. It is a tale much too complex to even summarize here, with twists and turns worthy of a thriller movie involving precious art. Amidst the hasty procurements, very creative marketing, perceived betrayals and reselling, the historical drama of Miller’s story is anything but exaggerated. One needs to read it to believe it. It is an extraordinary experience, a trip made vivid by Miller’s eloquent yet analytic and unvarnished writing style.

Even today, there is cultural, social, and political resonance with fine Chinese art, with the stakes being much higher than the average layperson gives credit for. After all, the Yixian Luohans are Chinese, and all overseas Chinese art, whether owned publicly or stashed in private hands, cannot be separated from the conversation and project of restoring China’s national dignity and core place in the world. Just as the outflow of art out of China represented a nadir in national fortunes, the seemingly insatiable inflow of art of all cultures into China these days represents a hunger to recover lost ground by its newly minted middle and mobile classes. China accounted for a staggering 39 per cent of the global art market in 2020, almost as much as the United States (27 per cent) and the UK (15 per cent) combined.

While repatriation is often a great deal more complex than what patriots (and even foreign sympathizers) might hope, The Missing Buddhas’ attitude towards this historical, multifaceted, and often sensitive subject is humane and careful eye. It stays focused on the human and flawed dimensions of its own story that, when taken together, help readers understand why ten pieces of Chinese sculptures are scattered around the world, all in museums outside of China. In this and many more ways, The Missing Buddhas boasts unique strengths among contemporary books on art and archeology and will benefit many that approach it from the angle of a Buddhist adherent as well.

See more

Legend of the Luohans – where the brethren really came from (Asia Society)

Arhat (Luohan) (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Geographical breakdown of the Art Market (Artprice)

References

Tony Miller. 2021. The Missing Buddhas: The Mystery of the Chinese Statues that Stunned the Western World. Earnshaw Books Limited.