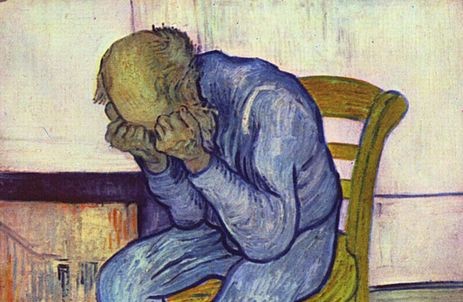

Just as the COVID-19 continues to spread and to cause chaos the world over, a wave of turmoil has been stirring in the depths of my being. Oftentimes, I wake up with a sense of despair, worrying about my loved ones and others who are most vulnerable during this health crisis. Other times, the concern is of a much more selfish nature: observing the empty shelves in the nearby stores, I fear that I may not have access to food, medicines, and other essentials in the coming days, weeks, months—however long this pandemic will endure.

More than anything else, I notice a strong craving: not only for the danger to be contained and eradicated, but also to have a clear idea about what is going to happen. I want things to be fixed, permanent, secure. I want to have control over the situation and I also want to have control over my emotions. As the unknown stretches ahead of me and more updates about the pandemic pop up on my phone, panic strikes. How will I make it through this crisis if I am an emotional wreck? How can I possibly be of help to those around me? While my initial instinct is to try to get rid of the negative emotions I am experiencing, a voice reminds me that this moment—as imperfect and volatile as it appears—is also a time for practice.

According to Buddhism, impermanence is the true essence of all things and there are a myriad of ways to become familiar with this universal truth. In Satipatthana: The Direct Path to Realization, Bhikkhu Anālayo highlights that bringing awareness to the presence of a hindrance can lead to “purification of the mind.” Because restlessness and worry is one of the five hindrances, this advice is particularly useful in regards to the emotions I am currently experiencing.

Anālayo writes:

“This technique of simple recognition constitutes an ingenious way of turning obstacles to meditation into meditation objects. Practiced in this way, bare awareness of a hindrance becomes a middle path between suppression and indulgence. Several discourses beautifully illustrate the powerful effect of this simple act of recognition by describing how the tempter Māra, who often acted as a personification of the five hindrances, loses his powers as soon as he is recognized.”

This ability to transform obstacles of meditation into meditation objects is perfectly illustrated by Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche in an episode of the Netflix series The Mind Explained. The monk shares that he experienced a lot of anxiety as a child, and that he eventually learned to use this perceived hindrance as an anchor for his practice:

“When I was young, I had these panic attacks. And my father said ‘no, don’t fight with the panic. You have to say welcome to panic.’ I’m not going to get rid of my panic. You can use anything as support for your meditation. So, I use my panic. I watch my panic. ‘Hello, panic. Welcome.’ So, in the end, me and my panic become good friend.”

In life, there will always be things that remain uncertain, scary, and out of our control. Instead of fighting our inner responses to such events, are we willing to bring awareness to them and to keep showing up for whatever arises in each moment?