Exhibit curator Davis Leung with Dr. Isabelle Frank, consulting curator, outside the Indra and Harry Banga Gallery

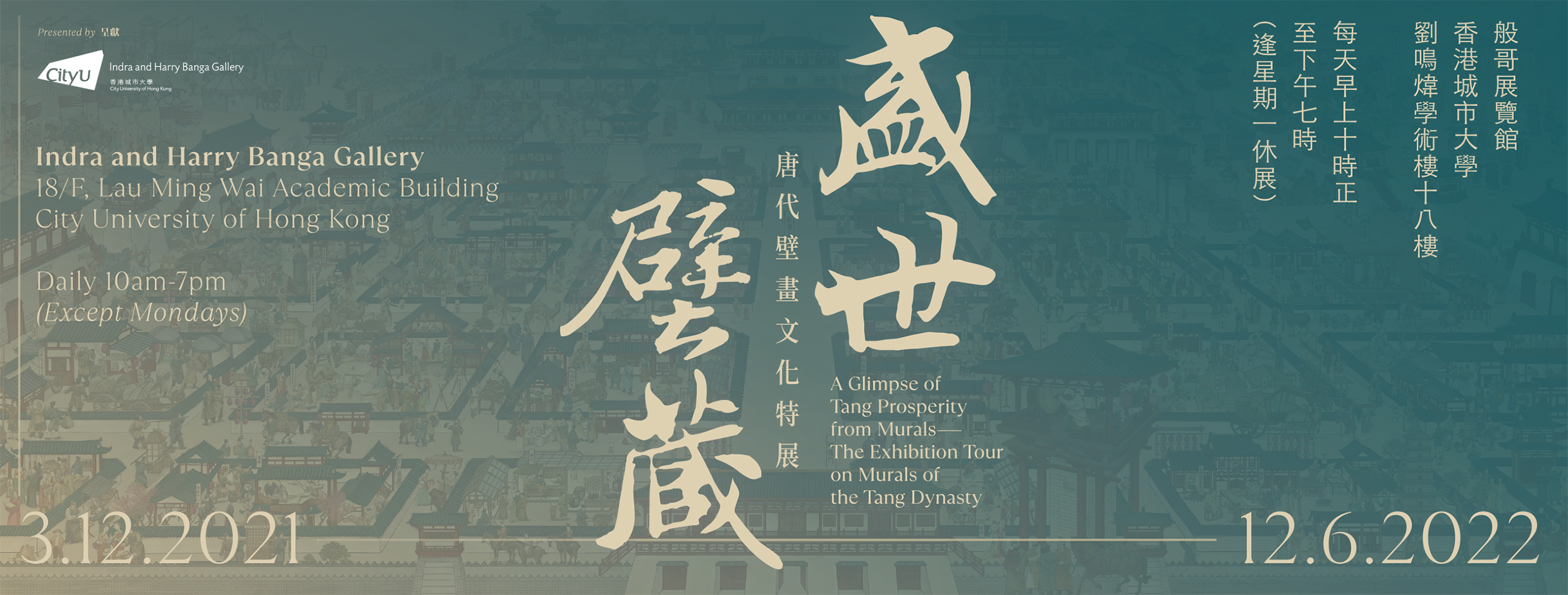

“A Glimpse of Tang Prosperity from Murals—The Exhibition Tour on Murals of the Tang Dynasty,” will be concluding soon. On display at the Indra and Harry Banga Gallery until 12 June, the exhibit showcases digitally restored mural art from several High Tang-era mausoleums, mainly the Zhaoling Mausoleum (the tomb of Emperor Taizong) and the Qianling Mausoleum (that of Emperor Gaozong, Wu Zetian, and several other members of the imperial household) in Shaanxi province. They attest to the engineering and artistic genius of the commissioned builders and artists, and also have the potential, pending further excavations, discoveries, and analysis, to answer more questions about the way Tang-era Chinese viewed their world and how the afterlife worked.

There are three “zones” demarcated for visitors. They all involve mixed media, including the music of Ng Cheuk Yin, a Hong Kong-based composer who composed a reconstructed track with Chinese and Central Asian instruments for the exhibit. The zones were: an Immersive Impression Zone (an original 4-minute animation video, accompanied by Tang-style music) and an Animation Zone, where four mural paintings (“Gate Tower,” “Polo,” “Ladies of the Court,” and “Musicians and Dancers”) are turned into animations with annotations and descriptions highlighting details and nuances of the murals.

The full number of 42 murals are presented the Imperial Tomb Mural Projection Tunnel, a corridor mimicking the long passages of the mausoleums and displaying the social customs of the Tang recorded in long-gone artists’ hands. These customs are: ritual architecture, palace ceremonies, and costumes and cosmetics. Adjoining cloisters explore the themes of etiquette and ceremonies, hunting and leisure, and court life.

One of the most tragic examples of a man born at the wrong place at the wrong time was Prince Zhanghuai (655–84), in whose mausoleum is the famous Polo scene, and one of the animated highlights. Han Yu’s (768–824) Biansi jiaoliu: A Poem Written for Zhang Jianfeng describes this scene best, which combines sporty boisterousness with martial rigor: “His body askew and elbow bent, the player hugged the horse’s abdomen; with lightning speed his hand sent the ball forth like a magical pearl.”

What of the gentleman whose tomb the Polo mural was painted for? It is hard to imagine someone so consistently not getting a break. Born Li Xian, Prince Zhanghuai was the sixth son of Gaozong (628–83) and the empress-to-be, Wu Zetian (624–705). This is the same Gaozong who, due to not only illness but over-affection for Wu, ended up ceding so much power to her that she was partially in control of the state from 660 onwards, before assuming complete rule from 665 to 683 as Empress Wu. While Zhang Huai was made crown prince in 675, in just five years in 680 he was stripped of that role and banished to Bazhou, or modern-day Bazhong County. He never returned to the imperial court in Chang’an, and died mysteriously in 684: shortly after the collapse of Wu Zetian’s reign. He was only 31. It is not surprising that rumors abound as to whether Wu Zetian had him killed, most famously by dispatching her enforcer Qiu Shenji to command Li Xian to commit suicide.

Among the murals at Qianling Mausoleum is a painting of the Sanchuque, or Triple Gate Tower. This is a Tang-era structure that is composed of a gate tower, flanked by two smaller ones. The Sanchuque denoted the Tang idea of “treating a tomb as a mausoleum,” meaning that an individual would be buried with the same rites and ceremonies as an emperor. The appearance of a Sanchuque was therefore the most solemn and respectful gesture accorded to a deceased person in Imperial China. This honor was given to two tragic figures at Qianling Mausoleum. Prince Yide (682–701) and Princess Yongtai (685–701) both died in their teen years at the hands of Wu Zetian, although accounts of exactly how they died are disputed. The royals’ father, Emperor Zhongzong, had been deposed by Wu Zetian, who was in turn Zhongzong’s own mother. Perhaps Wu Zetian was so irredeemably paranoid and cruel during her rule, to even her grandchildren, that when Zhongzong was restored to the throne, he felt it necessary to give his wronged children the highest posthumous honors. On the other hand, the Confucian vilification of China’s only empress (which Zhongzong no doubt encouraged to wipe out the memory of his mother’s aberrant Zhou Dynasty) gives us reason to be cautious about Tang records that play into the caricatures of power-hungry women.

These two mausoleums provide extraordinary material evidence about the way members of the imperial family were interred. At the same time, like with many grand tombs scattered around the world with great historical value and significant artifacts and art within, the grandeur of the mausoleums often masks flawed and human personalities, and the troubled lives of the people interred there.

Not only are we given a glimpse into court life in Chang’an, the imperial capital, but the exhibit brings to the present a long-lost confidence and robust optimism in Chinese civilization. This “Tang-esque” cosmopolitanism is something that contemporary China is, arguably to this stay, still recovering and relearning. After all, the High Tang represents the spirit of a carefree and confident people, a great nation that is prosperous and powerful. An age where the lights of Chang’an glimmer forever.

See more

NG Cheuk-yin

Tomb of Princess Yongtai (Shaanxi)

Related blog posts from Buddhistdoor Global

A Mausoleum of Marvels: Murals of the High Tang in Hong Kong