As part of a series in the Khyentse Foundation Goodman Lectures, the director of The University of Hong Kong’s Centre of Buddhist Studies (HKU CBS), Dr. Georgios Halkias, gave a talk about “Notes on the Earliest Tibetan Buddhist Canons” in February. Among these earliest canons, Halkias is referring specifically to the Karchag Phangthangma (dKar chag ‘Phang thang ka ma) (henceforth shortened to PT). The PT is a surviving, imperially sanctioned collection of Vajrayana Buddhist texts. Within this canon is evidence of an early cult to the Buddha Vairocana, the cosmic tathagata that embodies the Dharmakaya.

This imperially sponsored canon of the PT was completed after the construction of the first monastery of Samye in 779 under the emperor Trisong Detsen (d. 797), and the historical establishment of the first Tibetan monastic community there. According to Sonam Tsering, these Vinaya-centric events, including the first ordination of native-born monks under Indian preceptors, postdate the traditional periodization of the First Diffusion in Tibet by several hundred years, which Tibetan tradition expands to include the era of first emperor Songtsen Gampo (d. 650) and the first appearance of Buddhist texts in the 7th century. (Tsering 2020, 22–23; 27)

Exactly a decade ago in 2004, Halkias revealed in a contribution to the academic journal The Eastern Buddhist XXXVI just how important the PT is. It is “the last royally-decreed catalogue composed in the ninth century at the imperial court of ‘Phang thang in southern Central Tibet. Its contents and divisions reveal that it was based on two older imperial catalogues.” (47–48) Halkias noted that these registration-catalogues (dkar chag) are unique for being “definitive records of the official adaptation of Buddhism in the Tibetan Empire.” (50)

Scholars agree that Buddhism did not gain significant inroads into Tibet until securing support from the Yarlung court: both in terms of personal conversion on part of its kings, and also in terms of sponsorship for translation projects. While Halkias’ 2004 paper highlights many important aspects of the PT, too many to list here, one particularly compelling fact was how the PT betrays a “wealth of iconographic evidence for the prominence of the Vairocana cult in imperial Tibet.” (70)

In his lecture in February, Halkias also highlighted how the imperial Yarlung family ensured that among the tantric mantras in the PT, six works related to Vairocana Buddha were included. Halkias lists these six texts as:

- Mahävairocanäbhisambodhi-tantra

rNam par snang mdzad mngon par byang chub pa ‘i rgyud <7 Z>am/?o>(§XII,No.299) - Mahävairocanäbhisambodhi-uttaratantra

rNam par snang mdzad mngon par byang chub pa ‘i rgyudphyi ma <1 bampo> (§XII, No. 300) - Mahävairocanäbhisambodhi-tantra-aviparyäsa

rNam par snang mdzad mngon par byang chub pa ‘i rgyudphyin ci ma log par bshadpa <1 bampo> (§XXXII, No. 897) - Mahävairocanäbhisambodhi-tantra-vrtti

rNam par snang mdzad mngon par byang chub pa ‘i rgyud kyi stod ‘grel <1 bampo> (§XXXII, No. 898) - Mahävairocanäbhisambodhi-tantrapindärtha

rNam par snang mdzad mngon par byang chub pa ‘i rgyud kyi bsdus pa’i don <1 bampo> (§XIX, No. 501) - Short and long Mahävairocanäbhisambodhi-sädhana

rNam par snang mdzad mngon par byang chub pa ‘i sgrub thabs che chung gnyis <length not specified> (§XXXII, No. 918)

From this evidence, the Vairocana tantras were classified as official cycles that were taught in imperial temples (1 and 2), elucidated by senior clergy (3, 4, and 5), and were probably accepted as a mode of practice among said clerics and the Tibetan nobility in the Yarlung orbit. (6) These extraordinary historical likelihoods suggest that belief in the esoteric Great Sun Buddha had already been circulating in the Tibetan court, likely before the completion of Samye Monastery’s construction.

A Khotanese connection?

Devotion to Vairocana might even have been brought to the attention of the Yarlung court by the Khotanese monks that arrived in Central Tibet in the early 8th century (Tsering 2020, 23). This corresponds with the earlier compilation and translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra in the fifth century, which has probable Khotanese provenance. The possible transmission of a Khotanese-inspired Vairocana cult is geographically likely given the proximity of the oasis realm to Central Tibet and its economic importance, as well as the fractious military history between Khotan and Tibet.

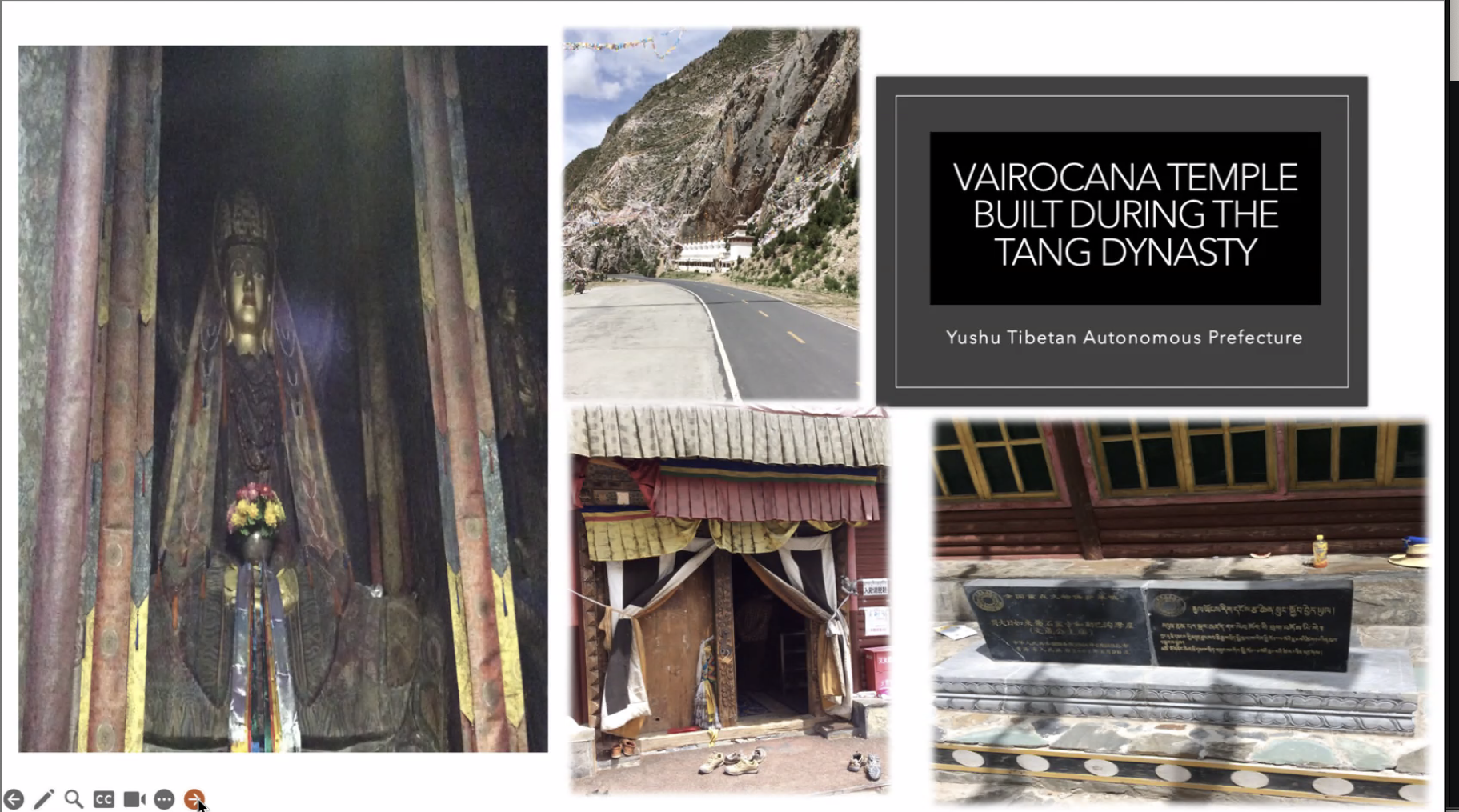

Finally, the Sun Buddha’s cult is materially attested to by the Vairocana temple in Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, which Halkias also discussed in his Goodman lecture. He had visited this small, Tang-era temple by the roadside at the bottom of a craggy hill some years ago.

The temple was built in the year of 806, during the reign of Emperor Tridé Songtsen. It is dedicated to Snow-Lake Vairocana or Nampar Nangdzé (rnam par snang mdzad), and local folklore attributes the temple to Princess Wencheng, the famous royal that travelled to Tibet as a bride of Songtsen Gampo. Samten Karmay disputes this, however (Karmay 1998, 55–65), and most scholars attribute it to the early 9th century.

The notorious difficulty of Tibetan dates aside (which have been deliberately muddled by historiographers from varying factions with political agendas), the timeline seems to suggest an external transmission of Vairocana worship that became, during the reign of Trisong Detsen and the tenures of Santaraksita (founder of Samye) and Padmasambhava (the fabled magician that subdued the land of Tibet for the Dharma), critical to the imperial cult’s reach across the land.

After all, Trisong Detsen and his retainers believed that reign of the Dharma and the Yarlung were one and the same. The Sun Buddha was the lord of all enlightened ones. It was only natural that the Dharmaraja, or chö-gyal, embody his light and power.

Reference

Georgios T. Halkias. 2004. “Tibetan Buddhism Registered: A Catalogue from the Imperial Court of ‘Phang Thang.” In The Eastern Buddhist XXXVI, 1 & 2. 46–105.

Samten Karmay. 1998. “Inscriptions Dating from the Reign of btsan po Khri lde-srong-bstan” in Samten G. Karmay ed., The Arrow and the Spindle: Studies in the History, Myths, Rituals and Beliefs in Tibet. Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point.

Sonam Tsering. 2020. The Role of Texts in the Formation of the Geluk School in Tibet during the Mid-Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. PhD dissertation. Columbia University.

See more

Article | The Lost Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan (84,000)

Related blog posts from BDG

A Divine Encounter: My Quest for Green Tara