A groundbreaking conference between Teresian sisters and priests and Buddhist scholars and monastics has just concluded at the University of Mysticism in Avila, Spain. During our time here among new friends and Carmelite masters, I had the chance to visit many churches in the Old City (the UNESCO-listed complex behind the grand walled fortifications) and those beyond the walls, each of which hold a piece of the life of Saint Teresa, Saint John of the Cross, or some other Christian figure associated with the Discalced Carmelite Order. Within each sublime structure we were reminded of the simultaneous grandeur and humility of the contemplative life, which demands a retreat from the lies and futility of the world and an inner turning that results in the elevation of the human being and a union with God.

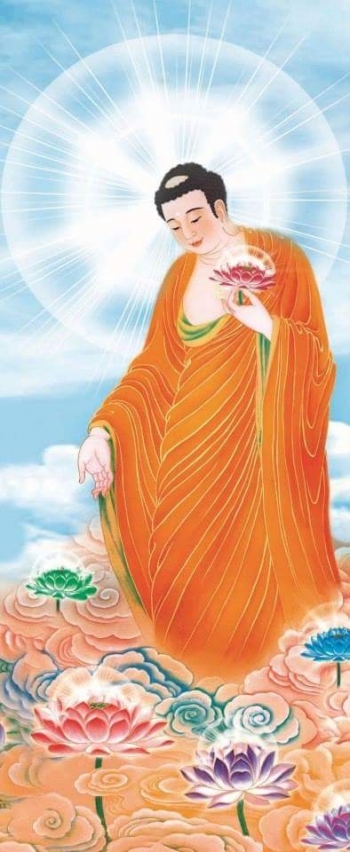

So, we turn inwards single-mindedly. What of the single-minded determination to become a Buddha, which is the ultimate goal in Mahayana Buddhism? What of the path to achieving Buddhahood, the quickest and most effective of which is total reliance on Amitabha Buddha’s 18th Vow and one-minded invocation of his Name? Isn’t this Buddhist anthropology also one of the highest elevation, of an evolution through bodhi to Buddhahood that parallels the metamorfosis of the Carmelite mystic into something God-like, a true human of light and love unified with all of God?

Within the six-character Name is contained all of the Buddhist path, and indeed all of reality. It embodies the means through which Amitabha Buddha reaches us and also is how we touch his infinite light. In some ways one might see the Mahayana Buddhist tradition as even more “mystic” than the Christian heritage for the reason that we human beings have the potential to become Buddhas outright. Ultimately, what Amitabha is, while seemingly distant from our capabilities and level of insight presently, is fundamentally of the dharmakaya, the Truth-body shared by all enlightened beings. Amitabha, after all, is a sambhogakaya Buddha, whose merits have come to fruition after eons and eons of cosmic practice and realization. We might rely on his Other-power now, but ontologically our potentiality is no different to Amitabha. Even the Teresian tradition must confess, despite this total and loving union with God, that God’s radical Otherness means that there is still that theistic distinction, that wall separating Creator and creation – even if it is so thin that it might as well not exist as far as the Teresian mystic is concerned.

Within the six-character Name is contained all of the Buddhist path, and indeed all of reality. It embodies the means through which Amitabha Buddha reaches us and also is how we touch his infinite light. In some ways one might see the Mahayana Buddhist tradition as even more “mystic” than the Christian heritage for the reason that we human beings have the potential to become Buddhas outright. Ultimately, what Amitabha is, while seemingly distant from our capabilities and level of insight presently, is fundamentally of the dharmakaya, the Truth-body shared by all enlightened beings. Amitabha, after all, is a sambhogakaya Buddha, whose merits have come to fruition after eons and eons of cosmic practice and realization. We might rely on his Other-power now, but ontologically our potentiality is no different to Amitabha. Even the Teresian tradition must confess, despite this total and loving union with God, that God’s radical Otherness means that there is still that theistic distinction, that wall separating Creator and creation – even if it is so thin that it might as well not exist as far as the Teresian mystic is concerned.

I do not think there is much consequence to attaching the label of “mystical” to the Pure Land tradition. I nevertheless think that there are mystic elements to the invocation of the Name. The more we recite “Namo Amitabha,” the more we are enveloped in infinite light and life and at death we are reborn in his Pure Land, expedited on the road to inconceivable Buddhahood. Amitabha knows us better than we know ourselves, and there is a striking parallel with what Carmelite theologian Dr. Rómulo Cuartas spoke of the union with God: we see ourselves as God sees us. We see that he wants to elevate us, not to have us simply remain as “mere” creations.

![]()

The mystic element of the Carmelites is almost subversive, at least if one adheres rigidly to a dogmatic and narrow vision of theism. I would note, however, that Teresian mysticism is a tiny minority within the Spanish Catholic Church, and that there is perhaps a correlation between its near-negligible public profile and the record-low Spanish participation in Catholic life: 18 per cent nationally. Spaniards have little patience for conventional Christianity and its negative expressions, from self-debasement for the remission of sins to the insistence on an eternal hell and a distinctly bloody theology where the emphasis is on sacrifice and death rather than resurrection. Many, some of who I spoke to, suffered real personal and emotional consequences thanks to these unrefined (one might say inauthentic) expressions of Christian thought.

There is a hunger out there for affirming visions of spirituality, particularly those which help people draw closer to a higher presence but in selfless friendship and intimate love, not terrified and guilt-ridden supplication. Speaking of the mystic elements of Pure Land Buddhism and sharing with others our friendship with the Buddha of Infinite Light may therefore not simply be an intellectual or theological exercise, but one of pastoral urgency.

[…] Is Pure Land Buddhism a “Mystic” Tradition?The Importance of Interreligious Dialogue and Goals for the Encounter: From the Buddhist Perspective […]