Dr. Ramala Sarma has been a scholar of Assamese culture and history, and how Buddhism has shaped the region for decades. She has always been inspired by how imparting lessons through symbols has been a pedagogical method for the ancient spiritual masters. These symbols of primal resonance later became the hallowed signs or objects for what we know as religious traditions.

“Today, the philosophical and moral significance behind the symbolic objects and their efficacy in removing ills and bestowing blessings, and conserving and harnessing positive energy, have helped these objects break the close boundary of faith and traditions and attain the height of the cross-cultural objects,” Ramala tells me. In this spirit, she founded Assam Amulet, her own business-cum-brand of such objects, sourced locally from Assam.

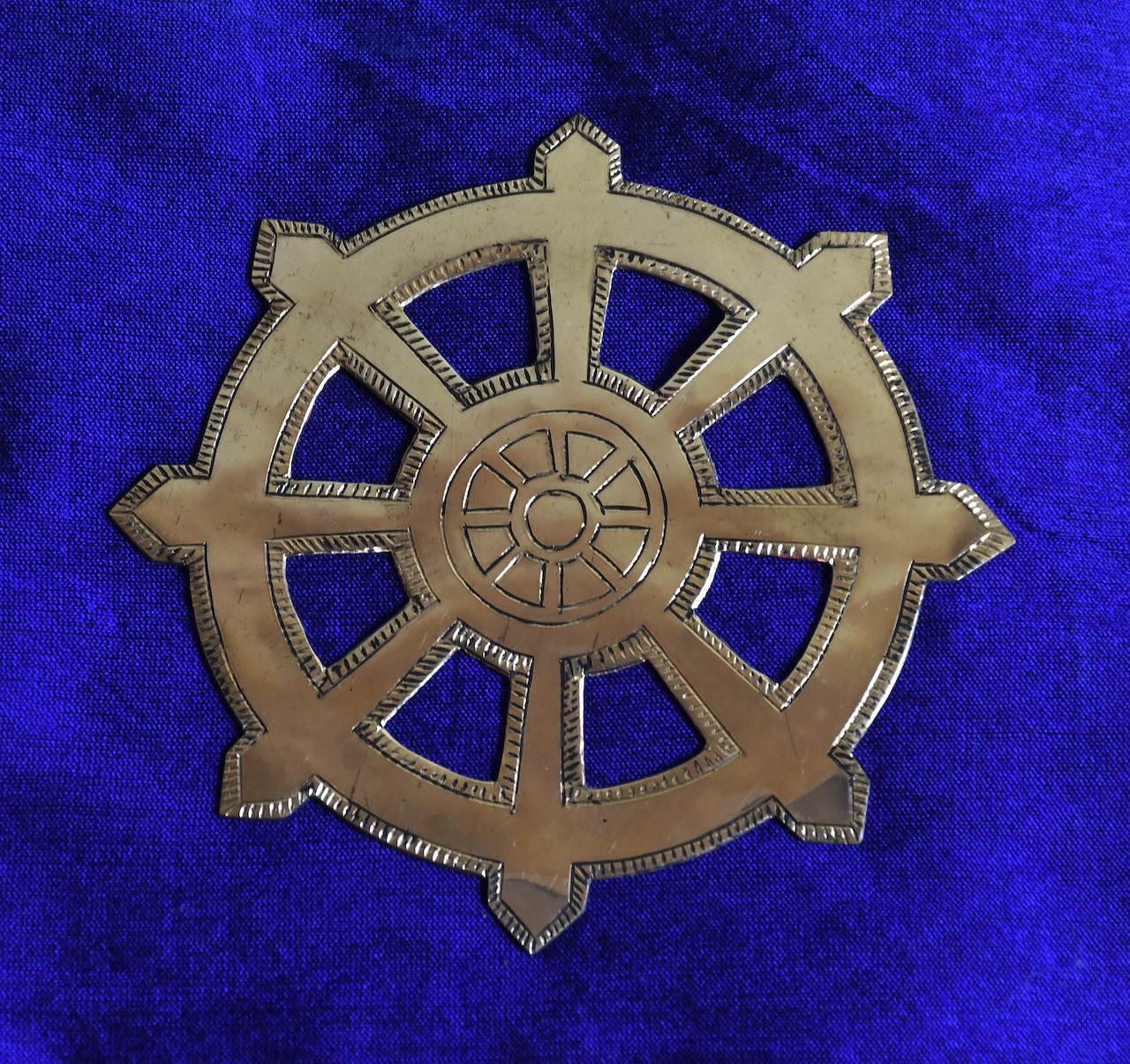

Apart from bearing a deep Buddhist philosophical significance, the symbolic objects that Assam Amulets manufactures promises to not only have an important role in meditative practice, self-transformation and personal growth, but also to help aura cleanse, encourage abundance, and aid in rituals. Obviously, to the beauty and elegance that Ramala is determined to express, they can be used as jewellery and decorative items as well.

“I am working with vendors of the bell metal industry at Sarthebari, Assam, to source the metals for these bells. This industry is the second largest handicraft sector after the bamboo craft. Famous for making the commonly used Assamese cultural items like kalah (water pot), sarai (a tray mounted on a base), kahi (dish), bati (bowl), gilas (glass), lota (water pot with a long neck), and tal (cymbals), this craft dates back to the 7th century,” says Ramala.

There is cultural pedigree behind these items. History indicates that Kumar Bhaskar Varman, the king of the Varman Dynasty of Kamrup (350–650 CE), gifted bhortal (cymbals) to Xuanzang, during the Chinese pilgrim-monk’s visit to Kamrup. This demonstrates that the industry was already present during that time, before assuming its apex aesthetic during the era of Ahom rule (1228-1826).

Ramala says that the most challenging part of this handicraft industry is its survival in the face of increasing machine-made products cheaper in material and value. The artisans used to produce traditional items of classic design are often reluctant to take up new products with new designs. “Hence, a question remains when it comes to the acceptability of their products beyond Assamese culture, and thus their development and sustenance when similar products are available in the market at cheaper prices.”

Assam Amulet seems relevant to me because Ramala hopes to use her brand to give a new market avenue to these artisans. They earn their livelihood solely from this industry. “These newly fashioned products have objectives in two phases: firstly, it is to enlighten the people with the teachings of the Buddha through objects. It will facilitate religious laypeople, regardless of their religious affiliations, to learn the great teachings on how to live a life of wisdom and peace through these daily usable items. Secondly, it is to give the bell metal artisans a new market avenue and wider acceptability of their skills and products.”

The uniqueness of the products does not lie necessarily in the design. You will probably have seen them before. Rather, their exquisiteness lies in the material, skill, and place of production. It is the first of this kind in the history of the bell metal industry of Sarthebari, Assam.

“In the opinion of many Buddhist monks I have talked to, the production of such hand-made products is very rare, or almost not in India,” says Ramala. “They said that no countries produce hand-made Buddhist hallowed objects with bell metal, save for Nepal. The bright shine that the bell metal products naturally emit coupled with the exquisiteness of these hand-crafted products will, hopefully, attract buyers from Northeast India and beyond. Here eight finished products with the trademark have been included. A few more are underway.”

This work, however, did not come without a challenge. It took Ramala around four years to give the idea a concrete form. As the artisans are used to the traditional way of producing things and are scared to try new designs, their incompetence and eventual reluctance to continue with the work often left her feeling hopeless. Then, finally, due to her perseverance and patience coupled with the blessings of the universe, the products came into being with a converging essence of luck, the three treasures’ blessings, and the Bell Metal industry of Sarthebari.

“I thank Rubul Deka and Khanin Deka, the bell metal artisans of Khudra Gumora (Santipur), Sarthebari in the Barpeta district of Assam for producing the items. My humble gratitude goes to Prof. Wangchuk Dorjee Negi, Vice Chancellor of the Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Education (Deemed to be University), Varanasi, and Ven. Karma Jnanavajra for helping me understand properly the philosophical significance behind the Buddhist holy objects. Their kind support and blessing worked as a dose of inspiration during my work,” says Ramala. “Last but not least, I am humbled to the Almighty and the cosmos for enabling me to think of this new idea, and produce and trademark Assam Amulet.”