My aunt, who I had dinner with the other week, is a pious Christian. She wears a cross necklace, which combines taste in luxury (the cross looks like one of those glimmering crystal or diamond encrusted ones) with personal piety. She has never stopped doting on me just because I wear Buddhist mala beads made of bodhi wood around my wrist, beside my humble Swatch (the latter choice being perhaps the more sacrilegious). My beads’ convenience and utility are, like her cross necklace, a relatively recent adaptation for lay devotees based on the notion of “portable sanctity.” Christian and Buddhist ideas of sacrality have long been associated with not just convenience, but also the materials making up the physical manifestation of this sanctity.

The Indra and Harry Banga Gallery’s “Amber: Baltic Gold” exhibit goes beyond much more than religious concerns, since this type of fossilized resin famously touches science, geology, paleontology, and many other disciplines. “Amber: Baltic Gold” opened on 15 December 2022 and is running till 11 April. This is a magnificently presented exhibit, done in curatorial collaboration with Gilles Bonnevialle, general manager of the art school of Paris-Ateliers; and Nicolas Patrzynski, a specialist in audiovisual design and exhibition production and management. The items displayed consist of 240 amber artworks from the National History Museum of Latvia; the Latvian National Museum of Art; Association Tresors de Ferveur; the Fondation Fourviere–Musee d’art religieux; the Mengdiexuan Collection; the Liang Yi Museum; and other private collectors, designers, and artists.

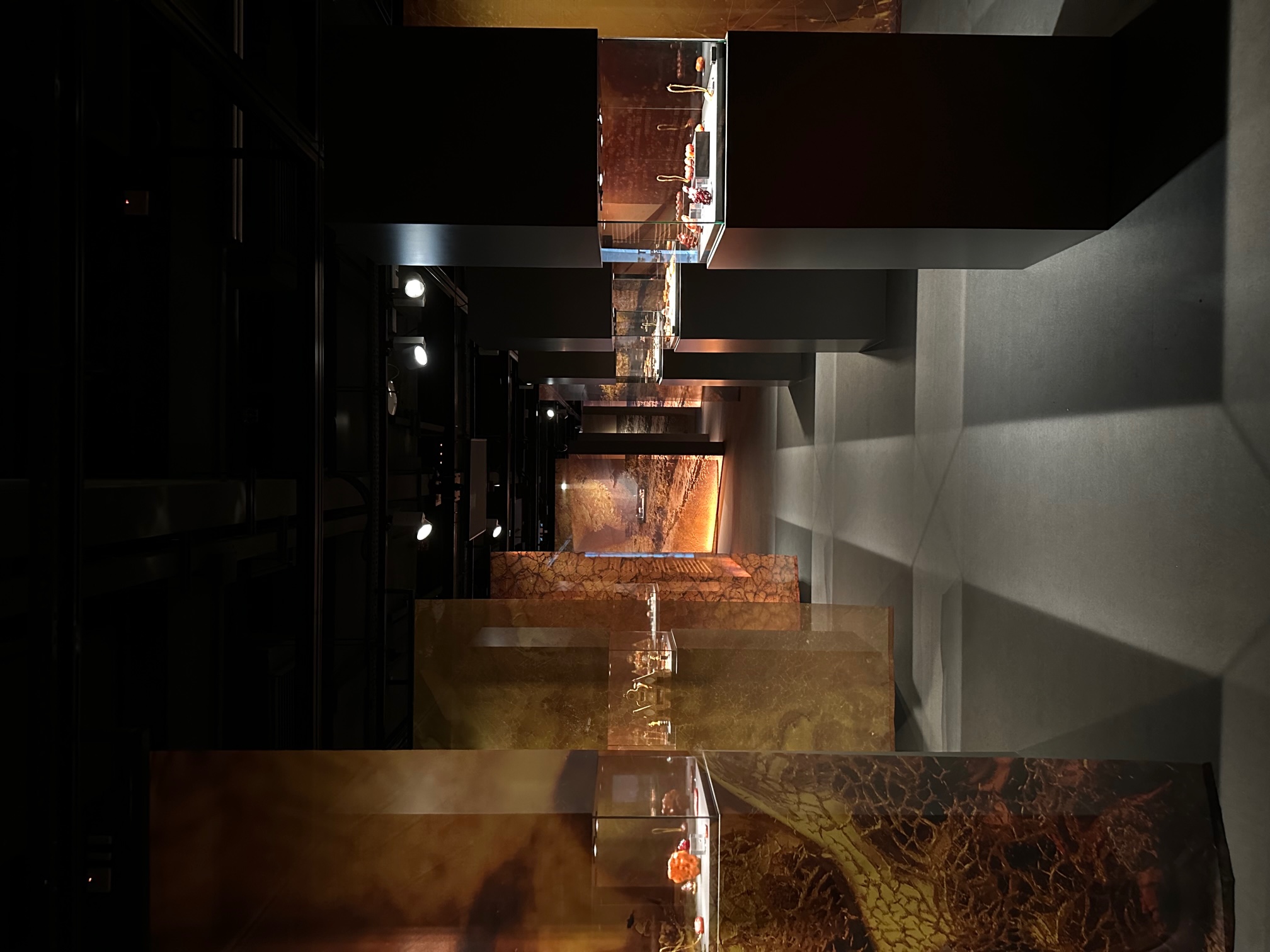

Rarely in Hong Kong do we enjoy this kind of exhibit focusing on a single material for craftspeople and artists. Indeed, until April, the ambience of the Gallery will evoke the experience of an authentic European-style museum.

Harry Banga Gallery. Image courtesy of City University of Hong Kong

different time periods. Image courtesy of City University of Hong Kong

As I was preparing this post, I stumbled on a Twitter photo with the caption, “A 12-million-year-old praying mantis in amber.” And that is what is so glorious about amber. It is a precious material that provides paleontologists, archaeologists, and geologists a peek into a moment of frozen history. It is a substance of deep time, reaching back into prehistory and long before human beings walked the Earth. In this sense the six-part exhibit is relatively modest, seeking to highlight about 3000 years of human use of amber. The significance of amber to science serves as the first part, laying out clearly the broader importance of amber beyond our small circle of art historians.

As the exhibit’s chief curator (and consulting curator for the Gallery) Dr. Isabelle Frank explains, amber is given its moniker because we have evidence for its earliest use from the Baltic regions, long before hints of its appearance in China during the Han Dynasty at the turn of the Common Era. Perhaps this was the result of a small trickle of merchandise passed along the Silk Road from the Roman-governed Germanic regions. Such discussions make up the content comprising the second section, with the third presenting the Chinese side of the story, with magnificent pieces of carved amber on display from the Liao Dynasty (916–1125). The Qidan/Khitan people were much more interested in amber than the traditional Han establishment. Here the distinct approaches between East and West become apparent: Chinese amber carvers loved to create exquisite pieces of artwork from the resin, from Buddhist divinities to mythical animals. Meanwhile, Europeans, much preferred to stay true to the original shape of the amber piece, with decorations for homes and jewellery to show off to friends made around the amber rather than “out” of it, like the Chinese did with different shades and hues.

©Bruno Vigneron, photographer

Amber remained popular among Chinese gentry and imperial families well into the Ming and Qing dynasties (the story of the fourth part), before suffering a precipitous decline in the Republican and post-1949 period. Amber remained in favor in the Baltic, in particular Latvia, well into the 20th century. The fifth section explores how Latvians saw themselves as heirs to the craftsmen that established amber workshops all over Europe. But rather than creating religious objects or pieces for nobility, as was common in the 16th century, pieces of jewellery and home décor centering amber pieces prevailed. Soviet-controlled Latvia went bigger and bolder, the more “amber-y” the better. Dr. Frank noted as our press tour moved through the sixth and final section, that contemporary artists’ taste for amber is something of a resurgent interest in the Baltic past, since there were temptations to break away from or abandon amber due to its association with Soviet oppression. It is commendable that this painful association has not been forever.

The contemporary expressions of amber come closer to being “installations,” on a grander and rarer scale than works from the medieval and ancient periods. Amber is not cheap. But to me, there is a certain profundity in the reduced scale of amber’s use in times past: whether for a set of Catholic prayer beads or a pendant of Guanyin’s image, there is power in the portable, jewellery made of ancient stuff that can be taken anywhere, traverse the world, crossing continents and cultures. Amber is not out of fashion and we all need reminders of our spiritual calling and comfort. I think amber, given its antiquity and adaptability, is a poetic reminder that no matter how things change (and society is changing very rapidly), something still stay the same.

Related news from BDG

Related features from BDG

The Buddha at Sea: Atlas of Maritime Buddhism and New Experiences in Museology

Related blog posts from BDG

Where the Lights of Chang’an Never Go Out: the Age of Confidence from Tang Mausoleum Murals

A Mausoleum of Marvels: Murals of the High Tang in Hong Kong