“In the early 90s, former monastics were quite rare in my region. Society did not perceive ex-monastics in a good way. They were seen as failures that could not fulfil their commitment. These days it’s accepted. You don’t need to be a monastic to help the Dharma.”

In telling me this, Choje Lama has highlighted a taboo subject in mainstream Buddhism. What happens when an ordained person – a monastic – disrobes? What are they to do when their calling is not what they thought it was; when their sense of vocation comes to an end? Changing careers, or leaving a relationship, can be extremely challenging. But perhaps leaving one’s religious calling is even more difficult. It can be a crushing decision to make, but it can also be liberating, especially when it is done for the right reasons. Perhaps a secular vocation is calling. Love might be in the air. There is every reason to disrobe if one’s karma is not to enter cloistered life. The only request that the Buddha made was that one’s path should be clear, and not muddled.

The true sangha is a Fourfold Sangha, not just a monastic community. Laypeople have a core role in the Buddhist tradition. But emotionally, transitioning from clerical authority to lay follower can be a time of inner turbulence and soul-searching.

Defrocking is more commonly discussed in the West, where monks and nuns leave the sangha more often. Support at the community and institutional level is often lacking, and many monastics, especially women, find that they cannot sustain their clerical life while working a job to make the rent. However, disrobing is also increasingly common in Asia, where monasticism in Buddhist-majority countries is no longer seen as an elevated position in society or an “easy life.” Parents nudge their children toward degrees and white-collar jobs, whereas to be directed to a monastery indicates a last resort. Without this prestige, the allure of the monastic life is restricted only to those drawn to religion: a considerable minority even in traditionally Buddhist countries.

Early on, when Wangchuk Topden (as Choje Lama was known back then) was attending school, there were not so many people that liked the idea of monks going to school. Yet years later, he has observed: “I believe it’s much better for monks to have some education aside from training to live in a monastery,” he said. “This is because we have to be realistic about how monks experience various disrobing factors. If you have a shallow understanding of the Dharma, the temptation to leave the monastery after graduating high school becomes strong. Families might exert pressure on the monks to return to lay life, even if they don’t want to.”

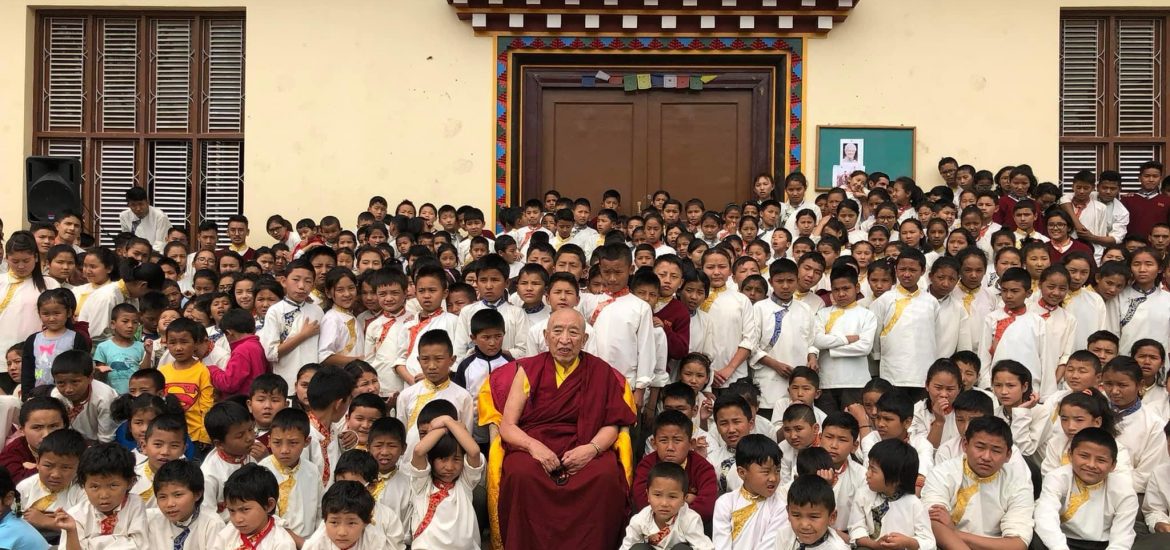

Choje Lama, unlike many of his contemporaries (and even senior teachers), has something to say about the relationship between monastic life and secular schooling. He is comfortable in his calling, that is for certain. However, that does not prevent him from acknowledging the fact that in a community like that of Namobuddha Municipality, where many boys can be ordained as monks, there is going to be a percentage of them that find such a lifestyle unsuitable or even intolerable. These former monastics should not be seen as turning their back on Buddhism, and deserve a support network.

“I still remember when we went to school, which was just a short walk from the monastery. Villagers could see little monks walking along the pathway every morning – a long line of sixty or so kids with backpacks containing heavy textbooks. People asked where the monks were going, and they answered school. After the villagers got over the initial surprise and reservation, they opened up to the idea.” There was somewhat of a crossover exchange. Thrangu Rinpoche already had wanted monks to have a secular schooling, while families felt that sending their children to Rinpoche’s monastery would mean a chance to attend SMD.

There were not many students to begin with. After the first 10 to 12 years of fee-paying students, SMD grew in fame. Choje Lama recalls that people in the West began to hear about the school’s burgeoning admissions and contacted Rinpoche, asking to provide funding. Rinpoche accepted, and by 2010 the school was funded enough to be able to prioritize admissions from children in poor families.

Choje Lama moves between the worlds of the monastics and the disrobed effortlessly. It is partly thanks to his own training. He attended SMD before having to transition to training in his religious duties under his Khenpo. This transition was hard, as he had to wake up earlier than all his peers and endure more rigorous reading and meditation. He was the first monk to graduate from high school, and he has fond memories of attending the shedra (this refers to the educational program in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and nunneries, and is attended by monks and nuns between their early teen years and early twenties). He found himself enjoying helping monks with more practical skills like visiting the bank, handling financial transfers, or meeting foreign visitors. These experiences and encounters led to him feeling that monks needed chances to engage practically with contemporary society.

Eventually, some monastic alumni of SMD disrobed for various reasons. They would move to Kathmandu or elsewhere, finding work and raising families. “That means that when they return to the monastery, perhaps on holiday, they are looking to help with temple activities, or other ritual assistance.” Choje Lama also notes that ex-monastics have friends who still are in the monastery, so relations are still good. Friendships are easily maintained. The ex-monastics see their visits to their former monastery as ripening karma, an opportunity to repay everything they were given during their childhood. In a practical sense, they also seek the chance to repay the money that were spent on them by donors, when they were in a monastic role. “It’s a win-win situation,” said Choja Lama, “and so they will assist with rituals like 100,000 recitations of Avalokiteshvara or Maitreya prayers.”

Choje Lama told me that there is a registered charity that serves ex-monks and ex-nuns, Lhaksam Tsokpa. Its chairperson and treasurer hold have met with Choje Lama to discuss how there can be better communication between monastic institutions and former monks and nuns. “Most of the monastics went into their monastery when they were 8 or 9, so by the time they leave, they are young adults. Many of them have a sense of kinship or even duty to their former institution. There is usually no resentment or falling out, so the disrobed people are eager to help with pujas, participate in retreats, or serve tea and maintain order during religious events.”

Buddhism is more than just mere devotion. Knowledge and application of practice, including among monastics, can be encouraged. Even when he was called Wangchuk Topden, Choje Lama knew that the line between monasticism and the outside world, while delineated, was not as easily separable in real life. That is Choje Lama’s characteristic quality: understanding that religion must exist in real life, among real people. It is this sensitivity and empathy that would make him an ideal leader of Thrangu Rinpoche’s monastic communities in the years to follow.