When children are forced to leave their home because of the ravages of war, they do not just need a physically safe environment, where they can grow up in peace. They need psychological support, oft-times trauma recovery, and validation and recognition of the struggles they have gone through. Such validation can be integrated into a program of quality education for these children. War is collective suffering, and the children often do not know why they fled their home country, or only have bits and pieces of knowledge from their families.

Refugee children, as well as the peers that they come to share classrooms with, would benefit from learning about how to discuss the war, how to build cultural and emotional bridges, and how to provide each other with psychological support.

Refugee children’s schooling would have been severely disrupted when they fled their home country. Compassion and the desire to see these children grow to their full potential means that a holistic approach to integration is required, with time at school (where children socialize and learn most) being at the centre of these integration efforts.

One of the most important challenges of countries that have elected to accept refugee children is the integration of said children into the national, local curriculum. The most prominent example is, of course, the refugee children from Ukraine. As the humanitarian relief portal, ReliefWeb, reported: “Teachers will need support in facing language barriers, how to slowly incorporate the international students into a welcoming classroom, how to discuss the war, and how to provide cultural and psychological support to incoming students.” (ReliefWeb) There are various action points, with perhaps the most urgent being finding enough bilingual resources and teachers that can help Ukrainian students with settling into classes in a foreign land.

Ukraine’s refugee children overwhelmingly have the same reason for fleeing their country. Offering these children with the tools to discuss and share the pain of war is critical for validating the suffering they have endured, as well as understanding the fear, anxiety, and negative feelings felt by local children that are not refugees, but have inevitably been exposed to the war (through parents, media, and mobile devices).

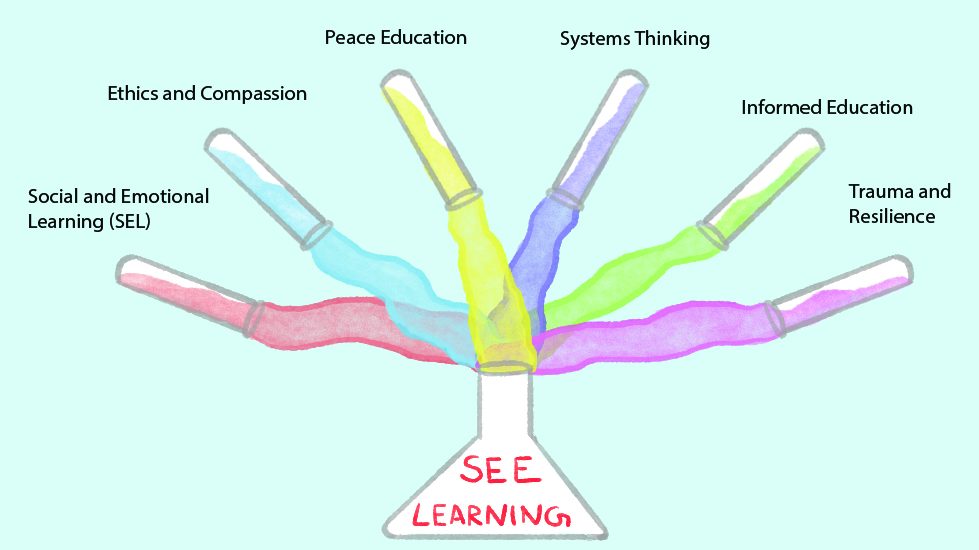

The integration of refugee children into a “conventional” classroom requires the deployment of programs that are emotionally rich and insight-based. We can look to SEE Learning as an example. Begun in 1998, SEE Learning is a K-12 education program developed by Emory University and His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Having successfully been used in many countries around the world, including many nations that are currently accepting refugees, the SEE website describes the program as building “upon the best practices in social-emotional learning (SEL) programs, but also expands on them by drawing in new developments based on the latest knowledge in educational practice and scientific research.” (See Learning) Specifically, SEE Learning has been applied in over 25 countries, the framework and curriculum piloted in India, Europe, the US, and South America.

That SEE is targeted toward kindergarten students indicates that such a program could be especially helpful for refugee children, and variations adopted for older children in primary school or beginning high school. The trauma of war and displacement is not an age-specific condition.

SEL programs have been in development for some decades now, but SEE adds four components to the already rich body of SEL techniques. These are based on what the Dalai Lama has consistently argued are critical components for a truly Buddhist-informed education based on secular principles: attention training, compassion and ethical discernment, systems thinking, and resilience and trauma-informed practice.

While all five components are critical, resilience and trauma-informed practice seems particularly applicable and relevant to displaced children. While countries accepting influxes of refugee children is a governmental or institutional acknowledgement of the suffering of war, it is quite another thing to educate the educators in talking about the trauma of war and fleeing a country, how to react when children are experiencing traumatic feelings, and creating an atmosphere that demonstrates empathy and cultivates resilience and mutual support.

To be trauma-informed, according to Resilient Educator, “means that one has a level of understanding about trauma and its impacts on an individual’s brain, body, emotions, and behavior. It is a commitment to learning more about trauma and viewing the individual as a person and not their behavior. Without being trauma-informed, a teacher may misinterpret a child or teen’s behavior in the classroom. Being trauma-informed recognizes that the undesirable behaviors are attempts to soothe emotional dysregulation, and this is often done unconsciously on the part of the trauma-impacted individual.” (Resilient Educator)

There are few more traumatic experiences than war, on top of the many unfortunate trauma incidents that children can endure, from domestic violence, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. War is devastating for civilians of all ages, but children suffer uniquely from this mass-scale violence at such an early stage in their lives. This suffering that causes children’s trauma will be the next instalment’s focus.

See more

Mapping host countries’ education responses to the influx of Ukrainian students (ReliefWeb)

SEE Learning

Essential Trauma-Informed Teaching Strategies for Managing Stress in the Classroom (and Virtual Classrooms) (Resilient Educator)