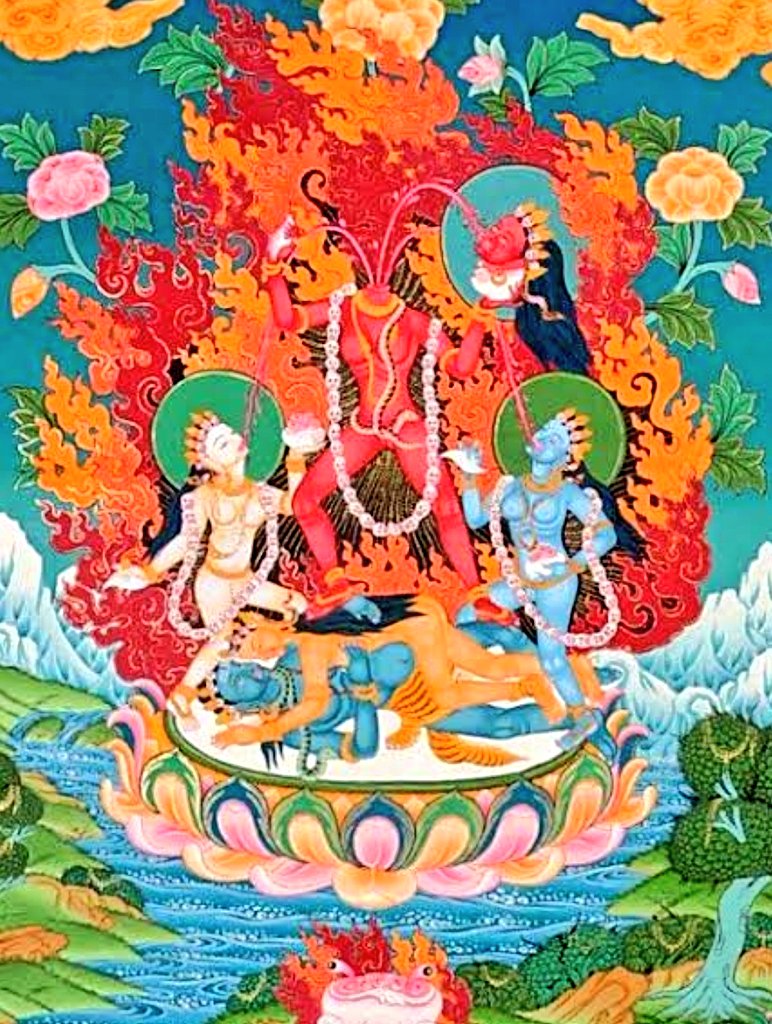

Chinnamunda (Tib. Uchema) is one of the most visually striking goddesses in the Vajrayana pantheon. Her name means “with a severed head.” She is regarded as a form of Vajrayogini and Vajravarahi and her Tibetan name is often found together with the names of the two goddesses: Dorje Naljorma (Vajrayogini Chinnamunda) and Dorje Phagmo Uchema (Vajravarahi Chinnamunda). The goddess is perceived as a Buddha in female form and as a fully enlightened being embodies the ultimate truth. She is also associated with Buddhist deities who offer their bodies as an act of supreme generosity.

Chinnamunda is associated with the Hindu goddess Chinnamasta, one of the ten Mahavidyas (aspects of the Divine Mother) who symbolizes the power of self-sacrifice. In Hindu Tantrism, she is perceived as a wrathful aspect of the Mother Goddess, the embodiment of self-sacrifice and the renewal of creation. Her self-sacrifice is expressed in the fact that she consciously beheads herself to feed other beings or the creation itself and it is associated with both destructive and creative forces. In Buddhism, the image of Chinnamasta completely overlaps with that of Chinnamunda. Texts and images of Chinnamunda are dated earlier than those of Chinnamasta.

The development of the cult of Chinnamunda is associated with the name of the 9th century Princess Lakshminkara. She was born in the mythical land of Uddiyana as a sister of the famous king Indrabhuti, who was a key figure in the early transmission of the Vajrayana teachings. Lakshminkara attained enlightenment after spending seven years in meditation, living in solitude, and becoming a great mahasiddha. She is considered to be the physical incarnation of Padmasambhava’s follower from the 8th century. After her death, she was reborn in Khechara, the dakini’s paradise.

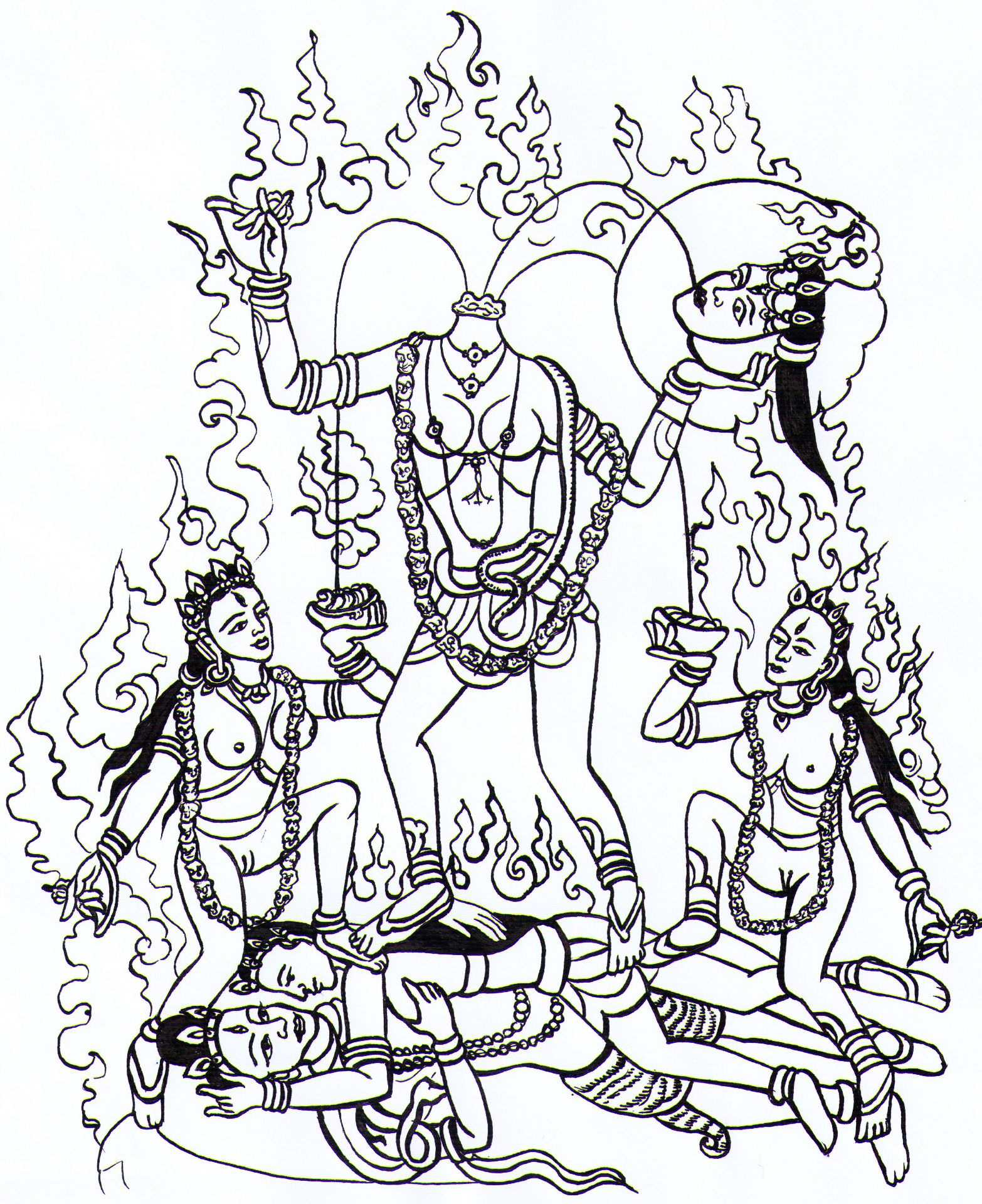

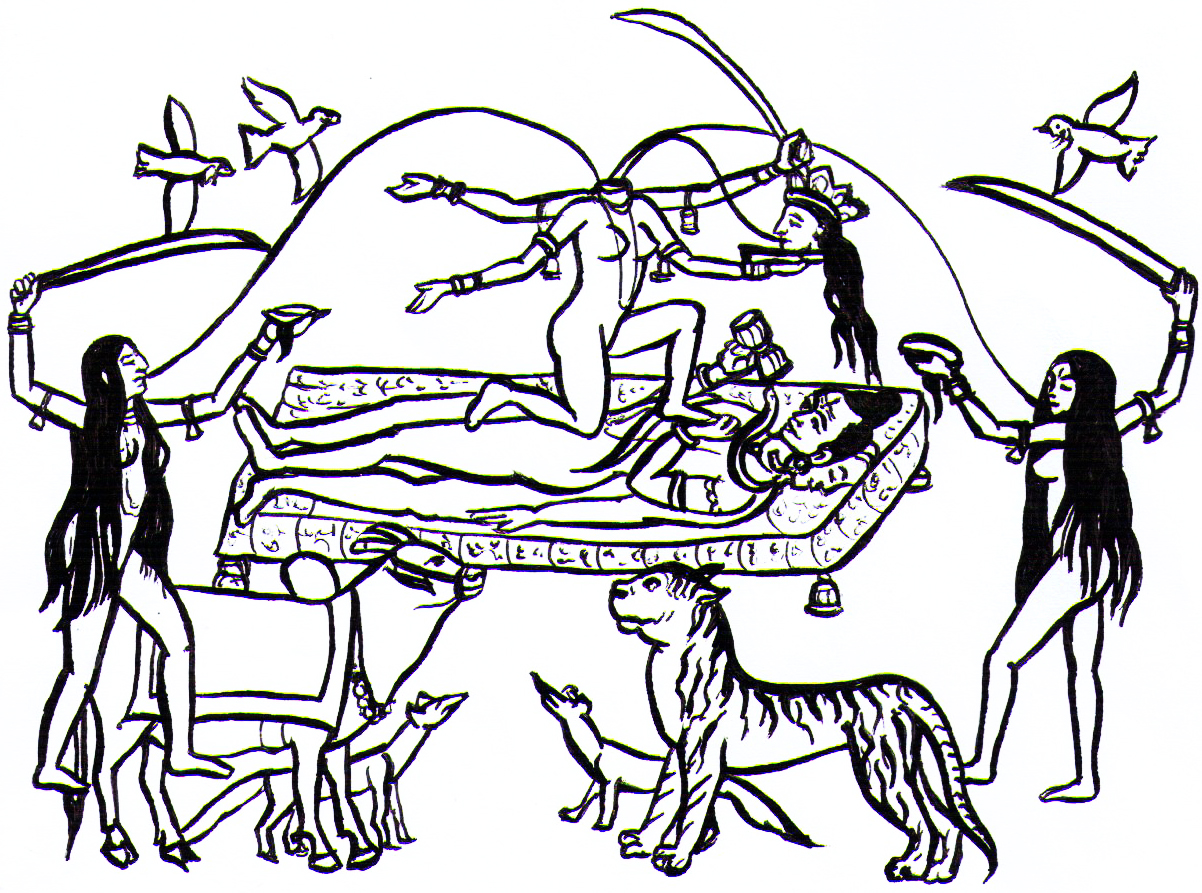

There are two texts in the Tibetan canon dedicated to Chinnamunda, and one of them was written by Lakshminkara. The other was attributed to Mahasiddha Virupa, who was her disciple and a key figure in the spread of the practice of the headless goddess in Tibet. Lakshminkara transmitted the practice of Chinnamunda to Jalandhari, who passed it on to the Indian yogi Kanha, a teacher of the sisters Mekhala and Kanakhala, who were known as enlightened yoginis. The sisters practiced the inner yoga of Chinnamunda for twelve years, and after attaining a high spiritual level, they went to their teacher to express their gratitude and respect. In order to test their devotion, he asked them for their heads, and they offered them without hesitation. In this way, they demonstrated that they have gone beyond the dualism of ordinary consciousness and have attained superhuman abilities. After this demonstration, Kanha returned their heads, congratulated them on their realization, and gave them permission to become teachers. They dedicated their lives to teaching and helping other beings to free themselves from suffering in samsara, and after their death they were also reborn to Khechara paradise.

Altough the goddess is found in various schools of Tibetan Buddhism, her practice is not so popular. One possible reason for that is that it was replaced by the practice of chö, which is also related to the motive of self-beheading. Meditating on her image, the practitioners identify them with the goddess and visualize how they are beheading themselves and channeling their energy.The practice is associated with the completion stage (dzogpe rimpa) of the advanced yogic meditation. The blood of her severed head symbolizes the life force and it is perceived as both the nectar of bliss and immortality. Those who master her practice can attain a state of immortality and manifest innumerable times in various forms, leading others to a state of liberation.

Thus, the image of Chinnamunda offers a dramatic portrait of liberation. It embodies the polarity of life and death as an important stage in the process of spiritual transformation. It expresses the Buddhist notion that when the illusory ego is destroyed, it opens the door to a higher reality and a deeper awareness. In Tantric Buddhism, the elimination of the individual self is associated with the Buddha state, which represents constant happiness and great compassion combined with non-dual wisdom. This wisdom is symbolically represented by the elixir of immortality that fills Chinamunda’s body and nourishes the entire universe. This is the message hiden behind her shocking iconography, to present spiritual perfection as a compassionate act by which the life essence is transformed into an elixir of salvation and the ego is transformed into an enlightened mind whose sole purpose is to free other beings from suffering.