Instinctively, my politics is anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist. However, I also appreciate the complexity inherent in human affairs and recognize that nuance of thought is required even in—perhaps especially for—matters as emotionally charged as the repatriation of cultural and artistic relics.

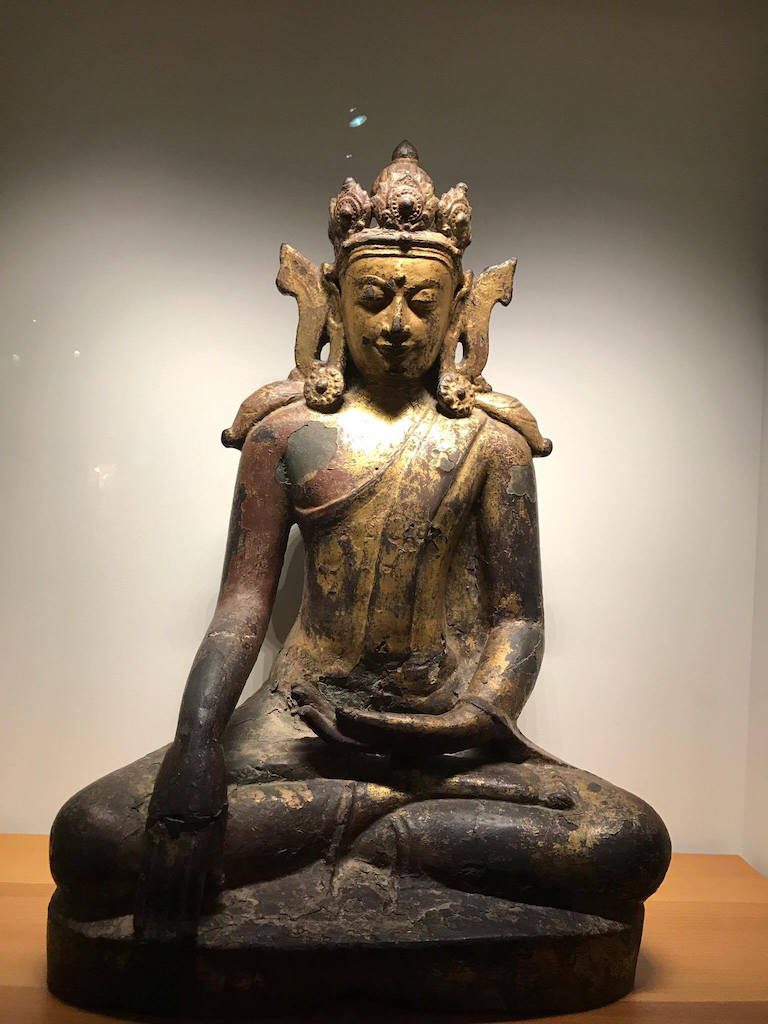

Today my fellow writer and blogger BD Dipananda has published an article looking back on his visit to the Guimet Museum in Paris, which houses some of the most beautiful Buddhist art in France. My political sensibilities inform my belief that the ideal place of a Buddhist artifact should be in a museum or temple in its home country. Yet many of the most beautiful historical items of the Buddhist world are scattered across the world, in New York, Saint Petersburg, London, Paris, and many more.

The world-class museums housing these artifacts have, I’m happy to concede, taken superb care of them. I’m also willing to accept that in the days of the Guimet’s founder, Emile Etienne Guimet (1836–1918), what seems commonsense and ethical to us now was emphatically not the majority opinion. This was an era when colonization was a common affair for seafaring empires, and war was a legal tool to settle unpaid debts or trade disputes—as China learned to a great and painful extent. Guimet was one of many in the late 19th century who traveled around Asia, blithely purchasing what he could afford and taking what no one else claimed. In cases of war, looting and carting back home the valuables of the defeated wasn’t just ignored, but often permitted.

It didn’t just take two devastating World Wars, the crisis of legitimacy and conscience in the West, and the collapse of the European empires to force about a change in thinking. Indeed, it was two factors—the illegalization of war as a means of diplomacy in 1928 and the rise of Asian nationalism (the idea that Asian countries should be organized into nation-states to win independence and a voice in the international order) that began pushing the center of political gravity in the postcolonialists’ direction.

Those of us who believe in a reasonable level of cultural repatriation need to appreciate that the idea of nation-states (a different thing from social identity or cultural consciousness) is a retroactive one imposed on Asian kingdoms, dominions, and empires. Very often those old orders had to be overthrown or reconfigured before any nationalist awakening could succeed.

The relationship between public and private is crucial in this debate: to what extent Western governments can mitigate the acts of private purchasers from a hundred years ago? By contrast, to what extent can individual dealers who legally bought or own some of these incredible cultural items right the wrongs of the past by freely offering their return? Very often, the items pass between so many different hands that it’s impossible to bring all parties together (some might no longer be in power, like governments, while private individuals might have passed away). This is why cultural repatriation is universally accepted only in a minority of cases, when all factions are considered satisfied (a rare thing indeed).

Finally, there is the additional conundrum of public institutions like the British Museum having to fend off the occasional uncomfortable question about having benefited from a state apparatus once geared towards feeding an empire. At least not a few scholars in the West admit to benefiting from this heritage, although they argue for those institutions to retain the artifacts. And what about the relationships between such museums in the West and younger counterparts in Asia?

There’re no easy answers. I think we need to cultivate goodwill among defenders of the status quo, guiding them to appreciate the hurt and anger that arises in the more nationalistically-minded when visiting places like the British Museum or the Guimet. Discussing repatriation is not an attack on Western museums, whose curators have important duties to the items they house. It’s not even an active campaign to “take back” artifacts. Rather, there needs to be an ongoing dialogue in order to hold the institutions that have the honour of caring for these artifacts to constant account. I do agree with Western curators that they technically belong to the whole of the human species. But they were also created in specific cultures, religions, and societies. That belonging, unique to certain contexts, must not be dismissed or excluded from any debate.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global