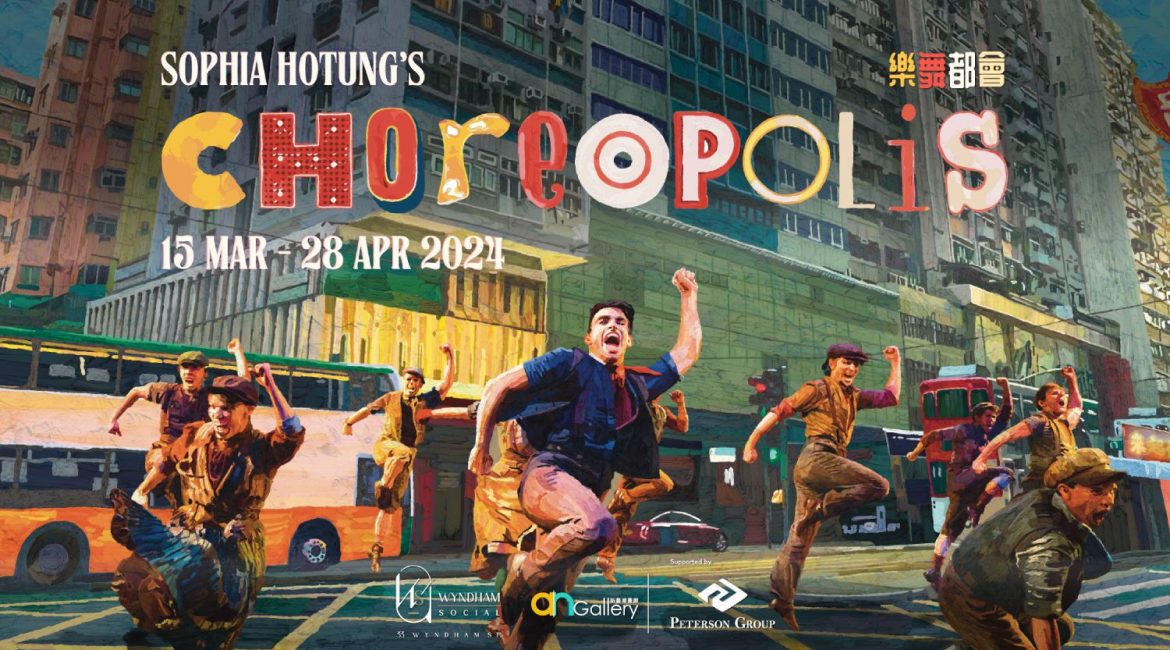

Since the age of 16, Hong Kong artist Sophia Hotung has had to work with unique physical limitations. She lives with several autoimmune diseases that reduce her physical activity for ten months out of the year. In 2024, she unleashed her characteristic creativity for her first solo exhibit at Wyndham Social, Choreopolis (running from 15 March to 28 April).

Choreopolis is a series of ten circular paintings of places that would be instantly recognizable to any Hongkonger, but with the added flair of scenes from famous theatrical plays and musicals commonly seen on Broadway and the West End added into the landscape: sometimes prominently, sometimes more subtly. The theme of movement and dance emerged from her lifelong love of these theatrical performances, as well as her appreciation of observing the city after COVID lockdowns had ended and soaking in its energy: an act that is precious to her.

Choreopolis is also a celebration of Hong Kong as a city of dynamism and internationalism despite all the negative press. “There are parts of Western culture that I know, namely through books and plays and theatre, but despite what people might assume about me, I grew up in Hong Kong,” says the 29-year-old artist. “That is how my Eurasian-ness comes through. But Eurasian-ness can express itself in many ways – for example, some Eurasians might have grown up in the West but know everything about Cantopop [Hong Kong pop music].”

When she thinks about how Choreopolis can challenge preconceived notions of the city, she is thinking of outside views of Hong Kong that lean toward the hyperbolically negative. “I’m used to people not thinking I’m from Hong Kong,” she laughs, “so I encounter people, often Americans, who are surprised when I say I was raised in Hong Kong” (born in the UK, she currently lives in San Francisco with her American husband). “They have the impression that Hong Kong is a toxic, capitalistic place that has been ruined by social turmoil and lockdowns—and I think such impressions have been influenced by biased frameworks trying to paint the East as somehow not as good as the West.”

Sophia’s love for Hong Kong and expressing it in Choreopolis is not so much about pitting Asia and against the West, and more about pointing out the simple facts about the city. “Everything works and is fast, everything is clean and colorful,” she adds. “This is a resilient city, and it is a diverse city, and it is a beautiful city.” Her work is inspired by this diversity, by nature and by intention, and challenges the idea that Hong Kong is past its prime or has nothing going for it.

Those that have followed Sophia’s art since her breakout book The Hong Konger Anthology (2021), will know that the Eurasian creator’s artistic career began relatively recently. Her “day job” is working on commissioned projects for charities or organizations she feels have a social purpose. This year, she is doing an art project for the SPCA’s new center in the suburb of Tsing Yi. Her way of doing art is painting on her iPad. It is more common for artists to specialize in digital art and drawing on the iPad than one might think. She has had many conversations about digital art with buyers skeptical of its value, charities, and other interest groups about valuing digital art and its meaning. Buying art with the hope that it will appreciate is one way to determine parameters of value, but buying art because one enjoys it takes on different considerations.

As a storyteller and lover of narrative, Sophia enjoys art that expresses a story or has an interesting story behind it. “My counter-question to this question will always be, ‘What do you like about art?’ If you’re buying art because you want it to appreciate in value, you’ll ask: what’s the reputation of the gallery? Is the artist dead or will they make more art in future? Is it one of one? Is it a print? But these questions often ignore craftsmanship, intention, and the story behind it,” observes Sophia.

“You’re looking at a totally different value system, so it’s really not valid to tell someone it’s wrong to value digital art. I like to say that if you like the look of it and it makes you happy when it is framed in your home or office, then that is valuable. If you’re in the art market for joy and pleasure, then it’s a question of you and your own values and preferences.”

Narrative and stories leap to colorful life in Sophia’s art, not only through the stories of the local Hong Kong locales but also, of course, the famous stories of the theatre. Her own story represents a journey about what she values in life and art. “My parents didn’t work in shiny companies and I was determined to have that nice office and that high salary in tech or in a big corporation,” she reflects. “I was obsessed with success or excellence. I was very cocky but at the same time, very hard on myself throughout my school days, maybe because I did well but didn’t get the highest grades.”

Sophia came of age during the “lean in,” Sheryl Sandberg era of the girlboss. It was in the 2010s when the media (and not a few Western politicians, sensing easy publicity) proclaimed that women could have it all. “Pant suits, Hilary Clinton,” she laughs, looking back on what seems an almost distant, bygone age. “That was going to be me. And then the pandemic hit. I think it really pulled the rug back and showed us women that we can’t have it all. There’s having children and childcare. There’s stuff that we have to acknowledge and that this shiny, Sheryl Sandberg way of looking at life is not healthy or balanced.”

Appreciating the mundane and letting go of attachment to excellence is a lesson that sounds positively Zen Buddhist. It took Sophia a long time to accept that there was nothing bad about normality or plainness. “It might sound a bit privileged, but there’s a lot of pressure on Hong Kong students, both local and international, to be oversubscribed to accomplishing stuff, be it extracurriculars or being at the top of their class. It’s everywhere, and everyone internalizes this, even when you tell kids it doesn’t matter if they fail or fall short. All my value was on what my resumé said.”

To fall ill and accept that she would never work in an office made Sophia reflect on what else might be worth living for, or what was more reliably of inherent value. “If I don’t have my job, what else is there?” she asks, reflecting a preoccupation that perhaps is shared by all capitalist societies.

“You don’t have a lot of control over your life,” observes Sophia, which is a valuable insight for any person. “You’re very limited, to this body, to this room. . . what is exciting and valuable in light of these limitations? It could be as simple as going for a nice walk down Hennessy Road and looking up its heritage. I had to pivot from thinking about attaining things ‘out there,’ which were out of reach, to thinking about value within, in myself.”

Sophia pauses, suggesting that there might be a Buddhist angle to letting go and orienting inward, “but looking at what you do have within your own parameters is actually very liberating,” she says. “I used to pass some of these places on my trips to the doctor and clinics, never really noticing them. They’re all very normal walkways, but focusing on the actual physical things in front of you, the most standard everyday road or path, can expose you to exciting new viewpoints, to vibrancy and movement that you didn’t see before. It is highly satisfying and makes the ambitions you had as a kid or teen quite irrelevant.” Experiencing less guilt and shame while still doing one’s best is a very good feeling.

Sophia has lived with autoimmune diseases for over 13 years, and she is concerned that discourse around “overcoming” illness and not being defined by lifelong conditions actually set people up to fail. “What that well-intentioned mindset does is make you ashamed of being ill. It makes you feel like you need to fight, but what you’re fighting against is yourself.” What she finds more helpful and sustainable is letting her illness limit her.

“There are things that I cannot do. I cannot stand and paint. If I faint, it just won’t work. I either force myself to buy an easel, brushes, and paint, and if I just start shaking and fainting it’s just part of the process. . . or I allow myself to recognize the unhelpfulness and futility of that mindset, which stresses me out, harms my body, and affects those around me. I will focus on the iPad and be limited to the iPad. But within those limitations there is so much to do. The technology has come far enough to be able to make brushes for the program that are unique to me.” The acknowledgment of her vulnerability has actually empowered her, including respecting her limitations when it comes to making art. “Knowing that I only have two months of true mobility each year makes me more focused about what I want to do, and I can work better and be more focused in that sense.”

When we think of opportunity, we tend to look outward. “I’m a big supporter of thriving within your parameters and limitations, and ‘drilling down’ – being happy and content and productive there. And there’s a lot you can actually do,” says Sophia, “and that goes back to appreciating the mundane, thinking about what you have and what you can get the most out of those. There is so much value in focusing on what’s already there rather than wistfully wishing for things you cannot have.”

Sophia concedes that it might sound like giving up to some, but to a Buddhist, this seems like true wisdom, and genuine self-compassion. “Everyone has different limitations and it’s so hard when you’re in a hole to listen to advice,” she offers at the conclusion of our conversation, “but for someone who’s in a place where they feel limited but also feel able to take on advice: sometimes it requires creativity and discipline and resilience. But there is beauty and potential and opportunity in the smallest of limitations.”