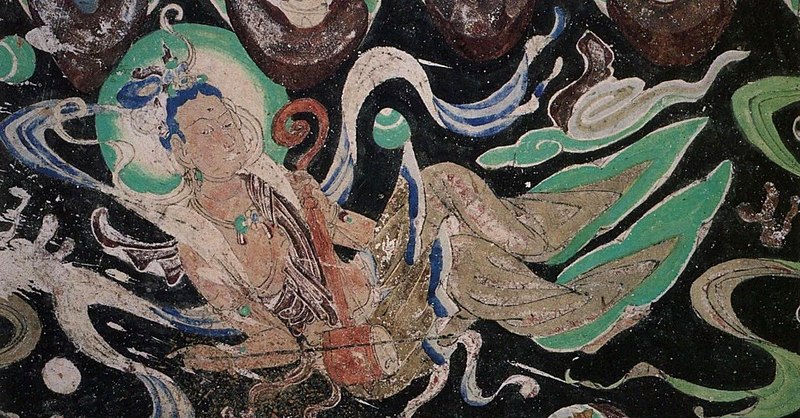

On 22 January, the Lunar New Year, our veteran columnist Nachaya Campbell-Allen had the good fortune to the London Philharmonic Orchestra’s premiere of composer Tan Dun’s “Buddha Passion.” It is striking just how this significant intersection is: a crossover between one of the UK’s many accomplished, world-class music groups and a Chinese-American composer who has been akin to a Hans Zimmer when being approached by film directors to lend an authentic yet dynamic score to their Asia-themed movies. Like many music aficionados that are steeped in Chinese history’s richness, he knows that the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang offer a peek into the musical aesthetics and methods of the time, a snapshot of how diverse people that came into contact with Buddhism’s teachings, art, and music would have set about performing music in religious and courtly contexts.

Tan Dun’s philosophy of “Buddha Passion,” six years in the making, is to translate or transcribe the murals’ depictions into music performances and bring them forward in time, situating them in the electric charisma and flair of a modern symphony orchestra. About two hours long, “Buddha Passion” is an operatically scaled composition for six singers, including two indigenous singers, and a double choir with traditional instruments. The premiere on the 22nd was joined by the London Philharmonic Choir and the London Chinese Philharmonic Choir.

In a musical feast for the senses, Tan Dun introduces Bach’s choral Passions to the stories and folklore of Dunhuang Buddhism, which was both dense in high philosophy (just recall the Library Cave, Cave 17, which Pelliot and Stein discovered and kicked off Dunhuang’s complicated modern history) but also replete with glimpses of the many divinities and mythological tales, spirits, and fantastic beings at the crossroads of commerce, religions, and politics.

Whether one sees Dunhuang as the entryway to China by desert from the west or, from the Chinese perspective, as the furthest outpost receiving foreign people and ideas, the city occupies a liminal space similar to the port cities of European colonial times or before: neither here nor there, but in different places at once. Tan Dun makes use of this in-between, almost mystic space to invoke ancient Sanskrit and Chinese texts to highlight six lessons from the Buddha: equality, karma, sacrifice, Zen, the Heart Sutra, and the union of Heaven-Earth-Mankind (tiandiren).

Another way this performance plays with time is Tan Dun’s deployment of the xiqin (奚琴), a two-stringed instrument that is theorized to have been the earliest huqin from which later Chinese and Mongolian bowed string instruments (like the erhu) derive. Tan Dun commissioned an instrument maker to create a replica xiqin, and it comes to life in the hands of Batubagen, an indigenous male singer. Batubagen and several others were handpicked by Tan Dun to perform alongside the London Philharmonic, including Sen Guo (soprano and indigenous female singer), Huiling Zhu (mezzo-soprano), Kang Wang (tenor), Shenyang (bass-baritone), and Yining Chen (pipa and dancer).

I cannot help thinking of the Six Perfections, the cardinal sextet of virtues in Mahayana Buddhism, and wondering if there was any intentional poetry behind Tan Dun’s six years of working on “Buddha Passion” or his selection of six singers and the six lessons. In any case, “Buddha Passion” harnesses modern tastes and sensibilities in European classical musicology as a vehicle for reconnecting with radically different music of the ancient Silk Routes. The Mogao Caves, in turn, manifest their musical traditions by being reinterpreted along the “new” Silk Road: a bridge that criss-crosses from modern Dunhuang to London. The latter, “Londinium,” is also an ancient city, connected to spatial and temporal invocations in the present.

Through the British Museum and the British Library, London is also intimately connected to the modern period of the Mogao Caves and the broader history of Western-style archaeology. From the Romans to William the Conqueror to its final apotheosis as the heart of the British Empire, London bears a complicated legacy borne out of a history of taking and being taken, a dynamic that cannot be ignored in contemporary Buddhist Studies in China. Yet music also presents another kind of meeting, perhaps of the rawer kind: an emotional coming together of different time periods and groups of people. In the comfort and camaraderie of the concert hall, disputes and conflicts of ancient times are laid to rest, and cross-cultural communication reaches its pinnacle through the universal language of music.

The premiere’s finale received a standing ovation. Perhaps that is the only answer one needs to all these discussions and questions. What is the sound of not one hand clapping, but of hundreds? A triumphant musical tribute to both the Dunhuang heritage and Bach.

See more

Tan Dun’s Buddha Passion is a striking fusion of Chinese and western music — review (Financial Times)