I have not played Black Myth: Wukong, though I would like to. The new game by Chinese developer Game Science has not only found stratospheric popularity, breaking records in the West left and right. It has also found itself in an American-dominated (of course) culture war. I think it is excellent that a game based fully and unapologetically on a Chinese classic, Journey to the West, has captured the zeitgeist of online pop culture so completely. On social media there are even comparisons of Sun Wukong (otherwise known as Monkey) with another fan favorite, Kratos from God of War, with the overwhelming majority of netizens concluding that Wukong would easily triumph. The Greek-born hero would be lucky to survive against Wukong’s cosmic power.

Of course, people familiar with even the beginning of Journey to the West know that the Monkey King attained immortality several times over (including eating peaches from the Garden of Everlasting Life and taking Lao Zi’s pills of immortality). As such, he was functionally indestructible, and had a variety of mind-boggling abilities, from transforming into 72 forms and replicating himself from the hairs of his body, that displaced the entire celestial host of the Jade Emperor (the Chinese king of the gods). Only Shakyamuni Buddha, at the begging of the Jade Emperor was able to defeat him: first psychologically by winning a cosmic bet, and then physically by imprisoning him under the Five Elements Mountain.

The bet between the incorrigible Monkey and the Buddha is well-known. One description of Monkey’s futile gamble actually comes from one of my favorite comics, Mike Carey’s Lucifer. And it is the Abrahamic God, Yahweh, who recounts the tale to his rebellious son, Samael/Lucifer:

“The Monkey King boasted to the enlightened one of his great strength, cunning and resourcefulness. Buddha said nothing in reply, having nothing in particular to prove. Buddha’s silence drove the Monkey King to further and further extremes.

“‘You think you’re so great,’ he shouted, “you old, fat, sleepy god! I am greater than you. Watch, and I’ll prove it.’

“Then he girded himself and made a mighty leap. His strong legs propelling him high into the air – and across all the worlds – until he landed on the other side of infinity. Where five columns of white stone hold up the roof of the sky.

“To prove that he’d been here, he carved his name on the middle column, scoring deep into the stone. Then a second leap took him back across the face of creation. Back to the Buddha. And he told the Buddha of what he had done. ‘Could you jump so far?’ he demanded. You, so old and fat. Could you travel all the way to where the worlds end, in a single jump?’

“The Buddha made no answer in words. But merely raised his right hand, and showed it to the Monkey King – who recognized his own signature on the Buddha’s index finger.”

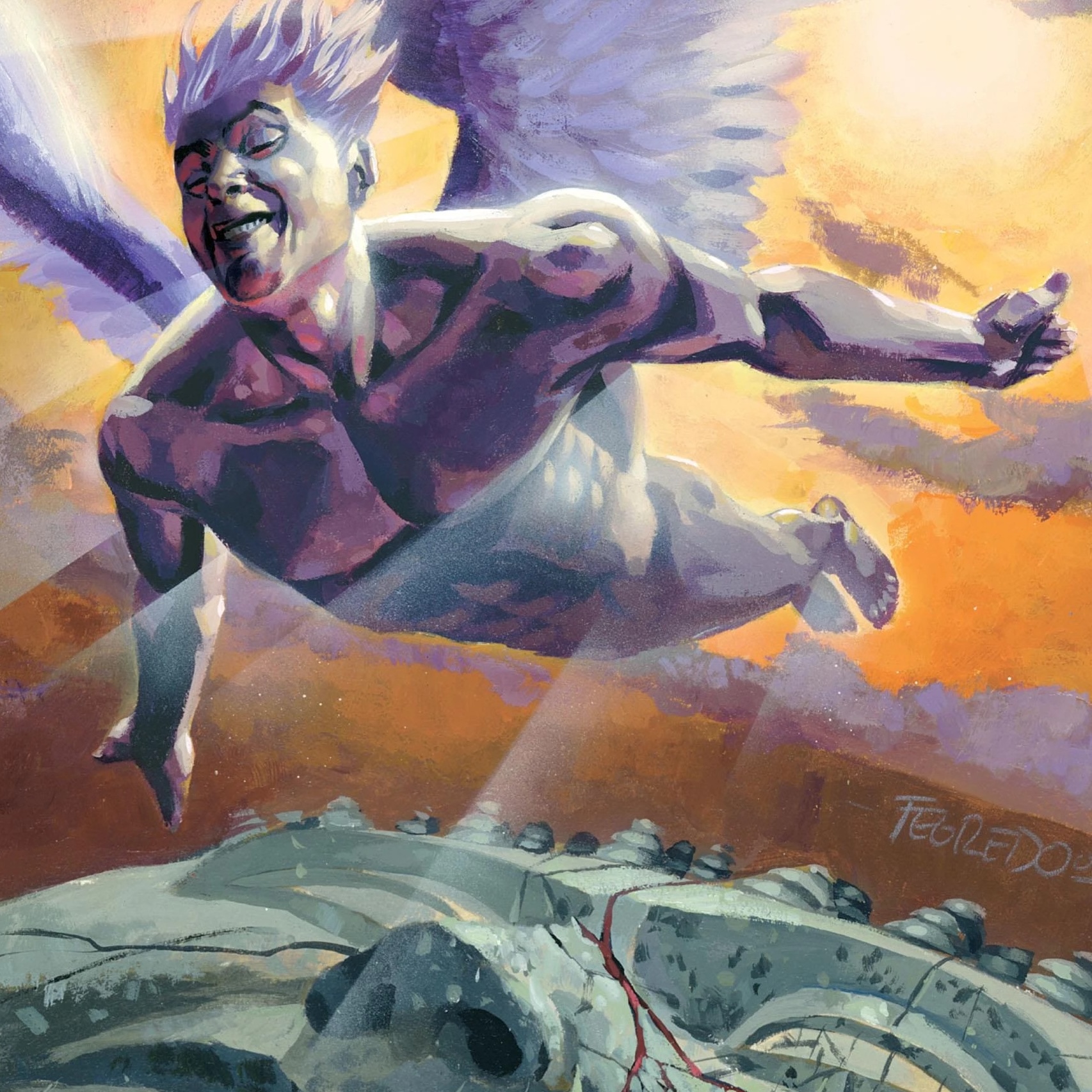

Lucifer Evensong (2007)

Thematically, Samael of Lucifer (and indeed, the Devil of many other works of literature like the Lucifer of John Milton’s Paradise Lost) does share a common thread with the Monkey of the original Journey of the West (and his successor incarnations in pop culture like Black Myth: Wukong). This consists of existential questions about the extent of our control over our own fates. Monkey’s trickster personality and fierce intelligence and resourcefulness are, from the outset, constrained by his subordination to the Buddha (and later on, to the bodhisattva Guanyin).

Even more gallingly, for someone as proud and powerful as him, Monkey is directed to serve and protect the eminently weak and borderline incompetent Tang Sanzang, who is very loosely based on the historical Xuanzang (602–64), who really did go to India to collect Buddhist scriptures. Monkey must learn humility, cooperation, and tolerance in the face of a long adventure alongside his comrades, Pigsy and Sandy, while also becoming selfless and self-sacrificing, before he totally abandons his old ways.

How free are we, really, when even a being as mighty as Monkey can do effectively nothing to alter his destiny with Tang Sanzang? It is surely a good thing that he learns the teachings of Buddhism and becomes a virtuous warrior for the Dharma. But the question of predestination – of Monkey’s journey to humility from the moment he met the Buddha – remains.

Lucifer, in a different way, cannot escape his past or future either. He operates in a world controlled irrevocably by his father, and even in his attempts to define himself against Yahweh, ends up only becoming his creator’s negative, a shadow. But God also has thoughts about this relationship, as he tells Lucifer: “You cannot be your own maker, Samael. None of us can. . . . I can’t apologize to you – or make you any amends – for the crime of being your father.”

But there is also something powerful in how Monkey reforms and changes himself, demonstrating that karma shapes the present, but the choices of the present can direct the future toward a different direction. To even make free choices, to have faith in their power, is the core decision that Lucifer and Monkey struggle with. Karma, in this sense, need not be imprisoning, but can be even freeing.

Lucifer ends with him rejecting God’s final offer and flying into the white blankness of infinity. Wukong, whose name roughly translates to “awakened to emptiness,” attains Buddhahood along with his master. Do these characters impose themselves on the emptiness, or become it? I think it is the latter, but yet . . . oh, but yet. . . their spirits remain, somehow, still defiant, insolent and impertinent.

In the face of divine destiny and reprimand.