Part of my April visit to China constituted a tour along the Hexi Corridor, which was hosted by the Dunhuang Academy’s Mogao Class (莫高學堂) subdivision. The Mogao Class specializes in holding classes and taking groups around sites in northwestern China (not all the sites are stewarded by the Dunhuang Academy). This year’s tour was the ninth iteration and formally called the “Toward the Hexi Corridor and Appreciating Caves Together” tour.

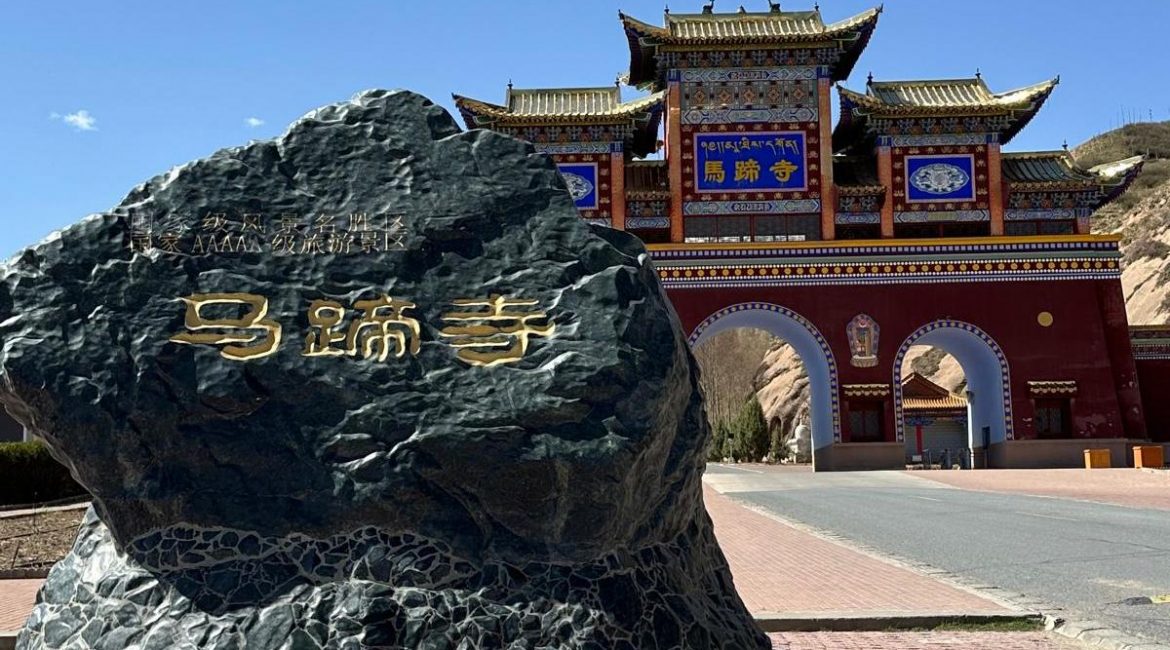

On the 23rd, we enjoyed (and endured) one of the tour’s most awe-inspiring and physically taxing days: a trip to Western China, Gansu, when we visited the Horse Hoof Temple Grottoes (mati si) complex in Zhangye. A long and pleasant drive to the entrance of Horse Hoof Temple under the blue skies of Sunan Yugu Autonomous County led us to a striking gate demarcating the entry to sacred ground. But that only heralded the beginning, as we set off in the shadow of the picturesque Qilian Mountains.

Horse Hoof Temple consists of a large group of grottos numbering seven different sites of historical, archeological, and religious significance stretching 30 kilometers. We do not know exactly when they were built, although the earliest art in some of the caves can be dated to the Northern Wei (386–534) and Northern Liang (397–460) periods, while some Chinese poetry seems to refer to the temple as early as the Eastern Jin (317–402). In the morning, we went into the lush, protected forest park for what was probably the highest area, the Golden Pagoda Temple with its incredibly beautiful apsara or feitian sculptures.

The name “Horse Hoof” (mati) is more commonly associated with the “main” Horse Hoof Hall (mati dian 马蹄殿), which is an important grotto at the North Horse Hoof Temple and renowned for the large hoof print near a very tall Buddha image. Horse Hoof Hall, in turn, is near the 33-layers-of-heaven temple (三十三天石窟) , which we visited in the afternoon. Like the Golden Pagoda Temple, it was ingeniously carved into the mountainside and eventually became 21 grottoes arranged in 7 levels, also resembling a pagoda sealed into the rock. Unlike the Golden Pagoda Temple, however, the 33-layers-of-heaven temple still has multiple shrines to Tara, Vairocana, and other tantric deities that pilgrims go to worship.

We climbed up several very cramped and dark flights of stairs (exhausting but exhilarating) to pay respects to the Green Tara shrine in the final sanctum, which is still lovingly tended to.

I am not sure why the “horse hoof” was left behind by a celestial horse ridden by the eponymous hero in The Epic of King Gesar, although this region is part of the “Gesar belt” of northwestern China (we did not have time to visit King Gesar Palace, which is also considered part of the overall grotto group).

There are not many reliable records of how the Horse Hoof Temple grottoes got their legend and came to be entwined with King Gesar. An even bigger mystery is who King Gesar was, a sometimes-frustrating question given that his heroic figure and his land of Ling permeates the intangible and bardic cultures of vast and diverse Eurasian oral and tribal cultures in Central Asia, South Asia, and northwestern China and Tibet plus Inner Asia.

The best explanation I have seen is that King Gesar might have been loosely based on a Central Asian warlord operating from Kabul. This military leader living in modern-day Afghanistan might have taken on the name “Caesar,” based on various political reasons relating to the Byzantine Empire and its effective defense against the Islamic war machine. See Frantz Grenet’s excellent study, which was published in a Brill monograph (2022) that is a treasure trove of the most updated research on Gesar.

As I reflected on once before when veteran actor Joan Chen was in Hong Kong, the world needs a big budget historical set piece, Kingdom of Heaven-style (2005) movie about Gesar. Even better, Horse Hoof Temple and the surrounding regions should be incorporated into a movie expressing martial ferocity and large-scale battles, Buddhist philosophical ideas, and mystic visions from meditation or trance. That would be magnificent.

Reference

Frantz Grenet. 2022. “A Historical Figure at the Origin of Gesar of Phrom.” In The Many Faces of King Gesar, Brill, 39 –52. ff10.1163/9789004503465_004ff. ffhal-03881984f.

Related blog posts from BDG

From the Capitals to the Corridor: A Visit to China’s Silk Road

From Joan Chen to Gesar: Stories to Tell, representing Buddhism in Cinema

State Sangha: Buddhism for the People

Conservation matters to China. It should be a core Chinese Buddhist concern

Art and Culture Brought to Life: Speaking with Lucy Guan of the Dunhuang Research Academy