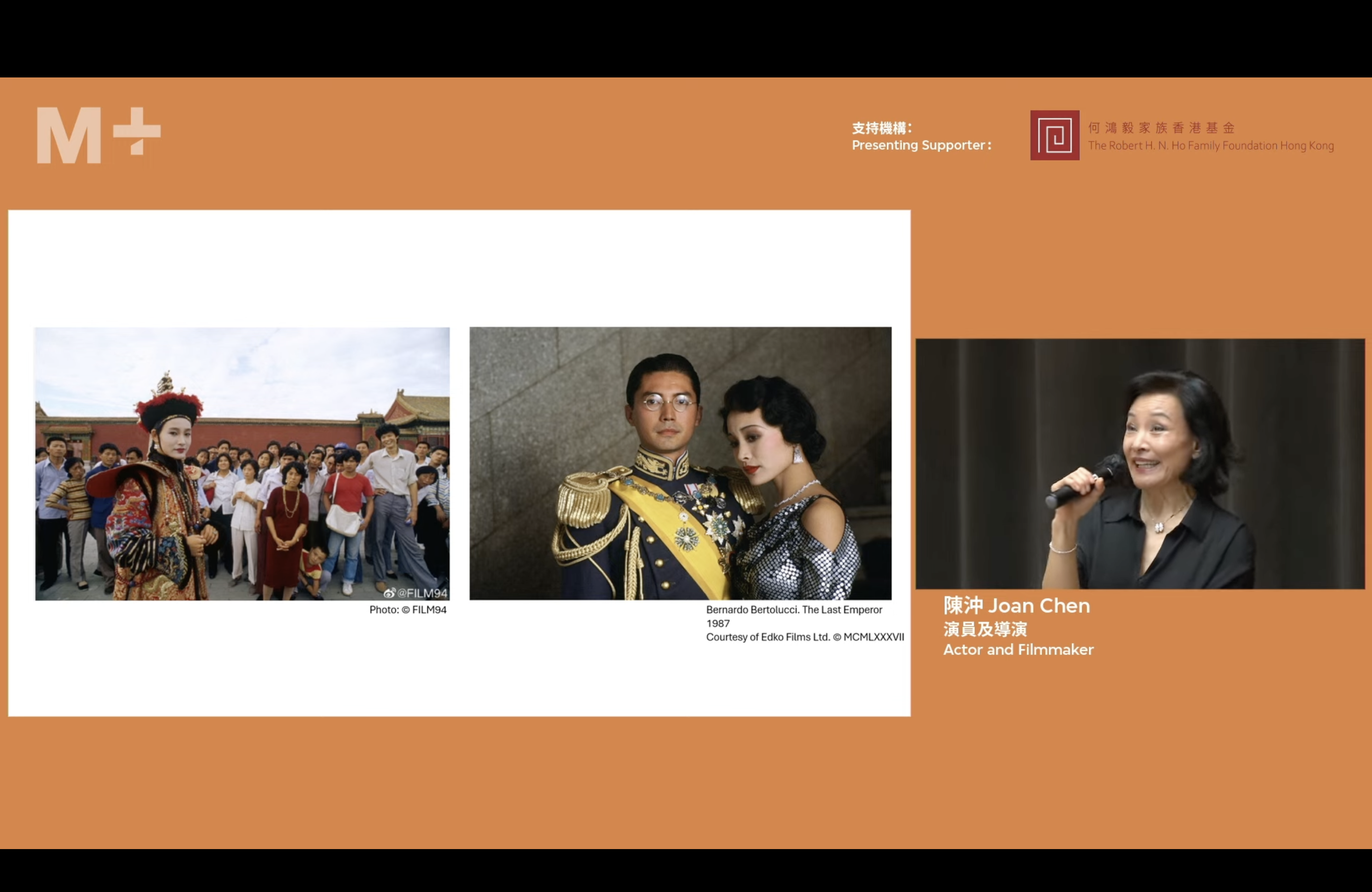

On 24 February, the hub of contemporary art in Hong Kong’s West Kowloon cultural district, M+, presented “Joan Chen in Conversation with Maggie Lee,” an entry into its Lars Nittve Keynote Lecture Series. The series invites influential figures and thought leaders from around the world to discuss arts and culture, and the big cultural projects that have helped shape and inform today’s arts ecosystems.

This series, along with the M+ Youth Integrated Learning Programme, are two public programs supported by The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Hong Kong since 2021. Joan Chen is a veteran name in filmmaking and acting, especially for those interested in Asian cinema. One of her most prominent roles remains famous for playing empress consort Wanrong in Bernardo Bertolucci’s (1941–2018) The Last Emperor (1987). As Chen noted in her conversation with film critic Maggie Lee a few days ago, Bertolucci presented an almost fairy tale retelling of Puyi’s life, on a manner of mythic scale that went beyond mere historical accuracy. One of the greatest achievements of Bertolucci was to capture the powerful presence of Vajrayana Buddhism in the Forbidden City, including in the incredible, haunting opening scene of Empress Dowager Cixi’s passing. Vajrayana Buddhism is, certainly compared to Theravada and Mahayana, the most well-represented Buddhist tradition in film today.

Led by Gaetano Kazuo Maida, Buddhist Film Foundation has been at the forefront of sourcing the best Buddhist-themed films. It is clear that directors see more value in communicating contemporary Buddhist values with films set in recent times. That is a wonderful thing, yet there is so much more left to do when it comes to expanding the potential genres and subjects. As an amateur historian, I would love more films that retell moments in the vast tapestry of Buddhist epochs, from a bold historical film about Padmasambhava’s relationship with Trisong Detsen at the court of the Tibetan Empire, to a dark fantasy retelling of pilgrim-monk Xuanzang’s adventures in India (why not even make his exploits particularly wild, like wrestling a naga or confronting a Brahminical cult by the Ganges?).

Be it sober adaptation or psychedelic dramatization, Buddhism possesses a vast array of concepts and characters that can reach deep into its philosophy and psyche to manifest truly striking film.

Some might raise their eyebrows or even be offended by my suggestion that Xuanzang do something outrageous in a retelling of his journey to retrieve the authentic Sanskrit sutras. But those familiar with Chinese literature already know that his odyssey was retold on an epic, completely made-up scale in the 16th century Ming novel, Xiyou ji. From a directorial perspective, a movie produced in this manner would be similar to 2019’s The King on Netflix, which was based on Shakespeare’s Henry V and not strictly accurate to the real life figure of the English king.

I would be delighted to see, furthermore, stories that try to capture the mythic power of texts like the Kalachakra Tantra or other various dharanis, or attempt to retell parts of great Buddhist epics. In particular, the story of King Gesar, the great Tibetan and Central Asian hero that rules over the mythical land of Ling, has been attempted sporadically in the past, but certainly not by a well-funded studio in the West or on a global scale. The story of Gesar enjoys a great antiquity and even greater complexity, having arose in Eurasia around two or three centuries before the Common Era. The epic was probably shaped and honed by folk balladeers around the 2nd or 3rd century BCE, with a “heroic” cycle of Gesar arising in the 7th century CE. The orally transmitted story retains many different versions, with its Tibetan versions emerging the early 12th century.

There are so many films produced about semi-legendary, even mythical, figures of both East and West. Gesar bridges all of them and there are simply so many gripping, enchanting ways in which even portions of his story could be told, let alone the entire thing. Perhaps – and I propose this seriously – Joan Chen herself might be a fitting director for such an epic engagement with Eurasia’s greatest yet most mysterious, movie-less folk hero.

See more

Related features from BDG

The Monk and the Gun – New Film from Director Pawo Choyning Dorji

Daughters of the Buddha: Buddhism and Film with Ven. Daehae Sunim

The International Buddhist Film Festival Returns! A Conversation with Gaetano Maida