One of my favorite books, which I bought many years ago as a student wandering the Waterstones on London’s Gower Street, was a discounted copy of Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s (1814–73) novella Carmilla, which was published one year before his death. It is the first and among the best works of sapphic vampire literature, a sub-genre within the broader body of vampire stories. In recent decades the vampire has been catapulted from the corpus of gothic literature to a permanent and beloved fixture in dark fantasy. From The Vampire Diaries to Twilight, not to mention endlessly creative re-imaginings of Bram Stoker’s eternal archetype, Dracula, the vampire has morphed into diverse figures that reflect our cultural preoccupations and collective fascinations.

Compassion for all sentient beings is a noble sentiment, but what about compassion for beings that will die if we do not offer ourselves to them to feast on? One gets echoes of Prince Sattva, one of the Buddha’s past lives in the Jatakas who offered himself to a starving tigress. There is a certain nobility and eroticism in offering a portion of ourselves, even our lives, to a darkly beautiful and tortured creature in need of nourishment. This act is something that authors of vampire novels, movies, and shows have exploited to great success.

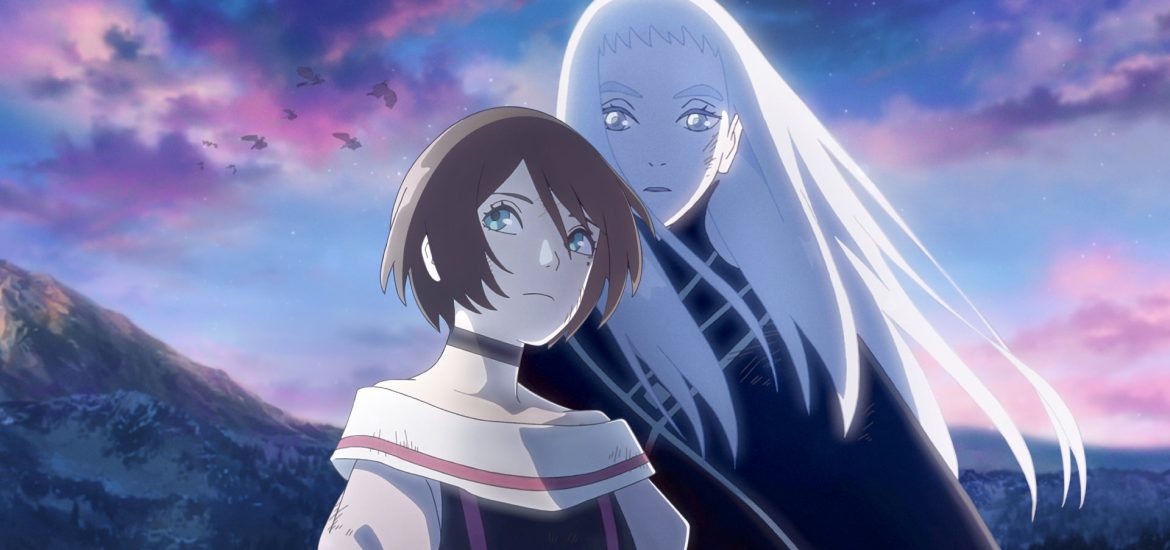

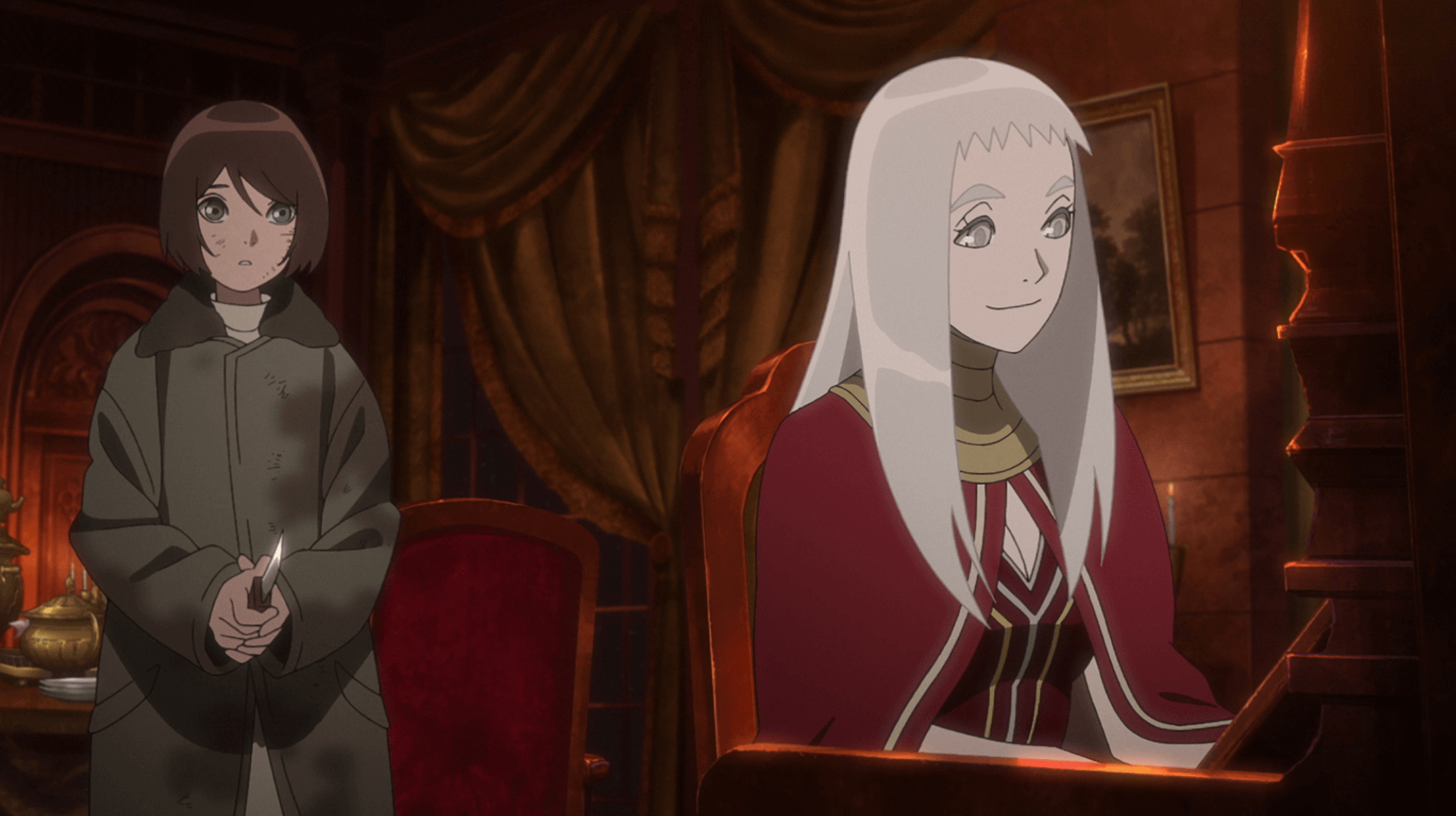

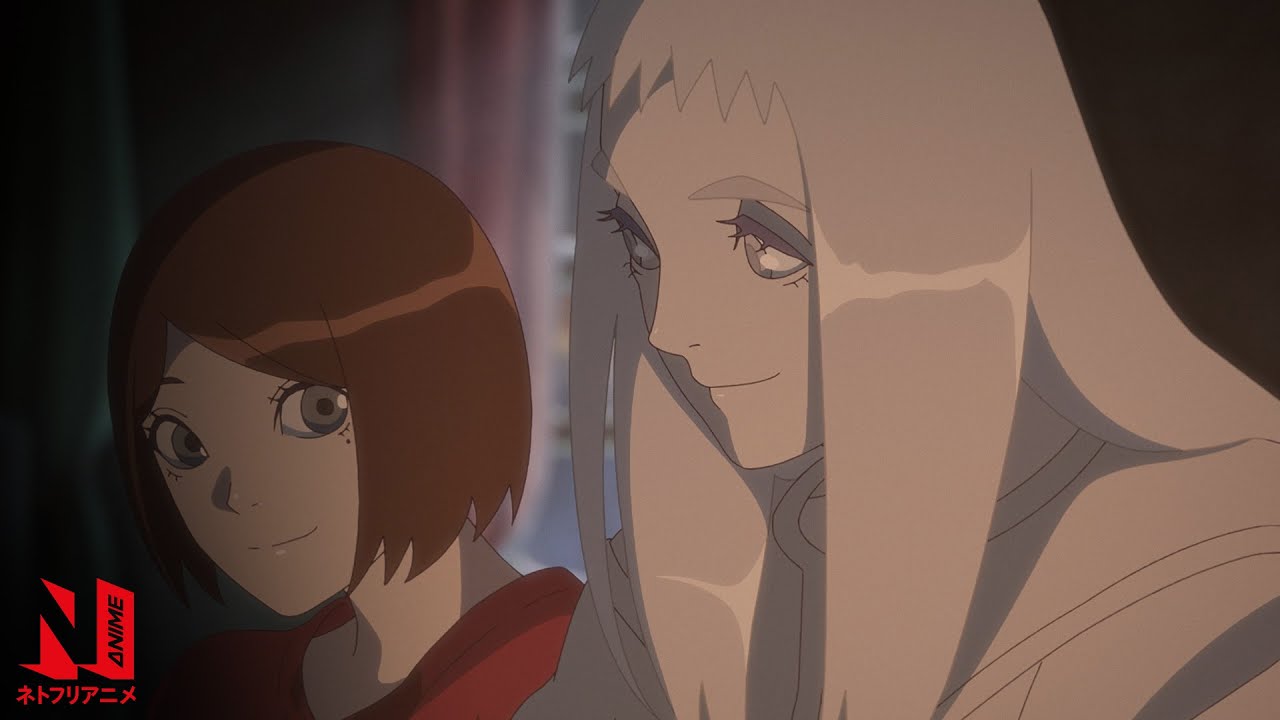

Netflix’s newest and most recommendable vampire anime brought me right back to Carmilla, but with 21st century motifs and themes. Wit Studio’s Vampire in the Garden is a snappy, five-episode series about a Romeo and Juliet-style love between military girl Momo and vampire princess Fine (pronounced fee-neh). It combines a dystopian, Russia-inspired setting with Victorian aesthetics (especially the interiors of rooms and buildings), and stunningly drawn landscapes and captivating action scenes.

There is an interesting theme about how vampires continue to sing and play music, while human beings lost the means and will to maintain the arts long ago. While this motif is never explored too deeply, it invokes the idea of how inhumanly strong and terrifying beings might be as human as we are. Music is also the means through which Fine and Momo are first connected. Momo longs for a world in which she can enjoy music freely, while the lovesick Fine sees in Momo a long-dead human girlfriend before falling in love with Momo on her own terms.

The anime, as with many good vampire tales, plays with our simultaneous fear of and attraction to monstrosities, what it means to give and take life (through the motif of blood), and the extent to which one can have loving feelings for creatures that can only survive by preying on us. Momo and Fine, who rebel against their respective worlds and destinies, love each other deeply, preferring to run in vain from a war that has no place for their bond. The story as a whole is not exactly original, from the doomed elopement and tragic ending to conflicted characters like Momo’s vampire hunter uncle Kubo and Fine’s male fiancé, Allegro.

One of the show’s best scenes in humanizing the vampire is in episode three. Fine introduces to Momo a cassette tape, which she inserts into their vehicle’s dilapidated player, before encouraging Momo to sing along. The song plays and the montage of the road trip that follows is something special. I think that is ultimately why Vampire in the Garden has echoes of Carmilla, even though Fine is a very different character to her predecessor. Both vampires are written with a certain vulnerability that invite us to see their duality as not just inevitable, but exciting and alluring (think: “I can fix her!”). Fine’s – and Carmilla’s – monstrosity is at the heart of their sentient being, and that is a philosophical consideration at once seductive and challenging. How else are we supposed to read the haunted yet wistful ending of the 1872 story:

“to this hour the image of Carmilla returns to memory with ambiguous alternations—sometimes the playful, languid, beautiful girl; sometimes the writhing fiend I saw in the ruined church; and often from a reverie I have started, fancying I heard the light step of Carmilla at the drawing room door.”

Can we harbour compassion and love for beings destined to destroy us, even if they themselves do not wish it? Cynics and pop culture watchers suffering from vampire fatigue might scoff: it is easy to love a beautiful or handsome monster that exudes sex and sensuality and lives in a gorgeous gothic castle, Byronically tormented about their own existence. Nevertheless, the question remains, just as it did for Prince Sattva when he decided the tigress needed to eat him.

If someone must die so that the other can live, who deserves to live, and who deserves to die?