The Jao Tsung-I Academy is a picturesque complex of renovated heritage buildings in the foothills of Mei Foo. It was named after Chinese polymath Jao Tsung-I (1917–2018), who has been called variously and all at once a sinologist, historian, painter, and calligrapher). Divided into upper, middle, and lower zones, it has a pet-friendly Heritage Lodge, centuries-old 2-storey buildings that offer accommodation for the creatively minded amidst a Chinese-style garden-scape. It has a Gallery and Heritage Hall, along with supplementary Exhibition Halls, many other facilities and rooms, and an unexpectedly excellent and comfortable café called Coffeeflow, which I always appreciate.

On 8 December, the Academy hosted “Bodhi Flowers in Blossom,” a unique initiative by Buddhist institutions and cultural bodies to mark the 25th anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to China. But this politically significant date also marks the auspicious conclusion of maintenance works at Po Lin Monastery’s Tian Tan Big Buddha and the famous 268-step staircase leading up to it. Last time I visited the Big Buddha, it was encased in scaffolding. Now, I suspect, is a perfect time to return as a tourist-pilgrim, to enjoy the Ngong Ping sights and restaurants while paying a visit to the more traditional grounds of Po Lin.

Accordingly, this exhibit involved religious and artistic bodies that serve as culturally influential bridges for Hong Kong and mainland Chinese mutual understanding: jointly organised by the Buddhist Association of China, the Hong Kong Buddhist Association, undertaken by the Po Lin Monastery, and co-organised by the Jao Tsung-I Academy, the Jao Tsung-I Petite Ecole of the University of Hong Kong and the Sun Museum.

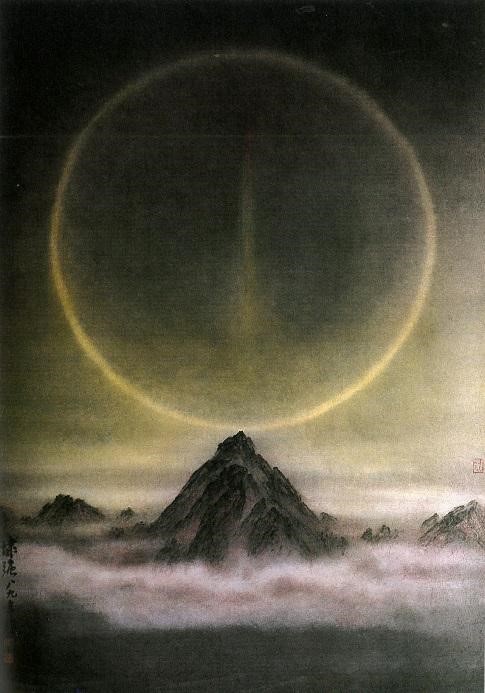

The exhibit consists of a generously curated selection of Buddhist paintings and calligraphy. It is divided into two sections. The first, “Treasures of Po Lin Monastery,” showcases 41 paintings and calligraphic works held by this iconic and authoritative institution. Most of the works of this exhibit were created by leading artists and scholars in a 1989 exhibition to raise funds for the Big Buddha’s constructions, eventually being gifted to the monastery afterwards. Names like Erya Deng, Gao Zhenbai, Zhao Puchu, Kuan Shanyueh, Chen Zhanquan, Jao Tsung-i, Ng Kuhung, Ha Bikchuen, and Auyeung Naichim will be familiar to aficionados of contemporary Chinese art, as the collection boasts the crème de la crème of Hong Kong art history. The mediums cover calligraphy, ink painting, oils, and prints, and the styles stretch from that of the Lingnan School to the New Ink school, to the contributions of overseas returnees to China or Hong Kong.

The second exhibit, “Paintings and Calligraphy by Chinese Buddhists,” features 63 works by 53 monastic and lay leaders from China. The creations here celebrate specifically the 25th anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover. They represent an affirmation of the People’s Republic’s stewardship of One Country, Two Systems and a statement of support from the Buddhist community. Contributors included Ven. Yanjue, president of the Buddhist Association of China; Mr. Liu Wei, secretary general of the Buddhist Association of China; Ven. Kuanyun, president of the Hong Kong Buddhist Association; and Ven. Siukun, emeritus president of the Hong Kong Buddhist Sangha Association.

The abbot of Po Lin Monastery, Ven. Jingyin, is a famously busy man, and has been so well before I was first acquainted with him as a teaching assistant during his days as The Centre of Buddhist Studies’ director at the University of Hong Kong. He was also involved with Buddhist Studies at Nanjing University, and eventually he came to be Hong Kong’s best choice for building and maintaining Buddhist links between the city and mainland China. The opening ceremony of this exhibit demonstrates the greater weight of his current work, as it was attended by some of the most important liaisons between Hong Kong and the mainland.*

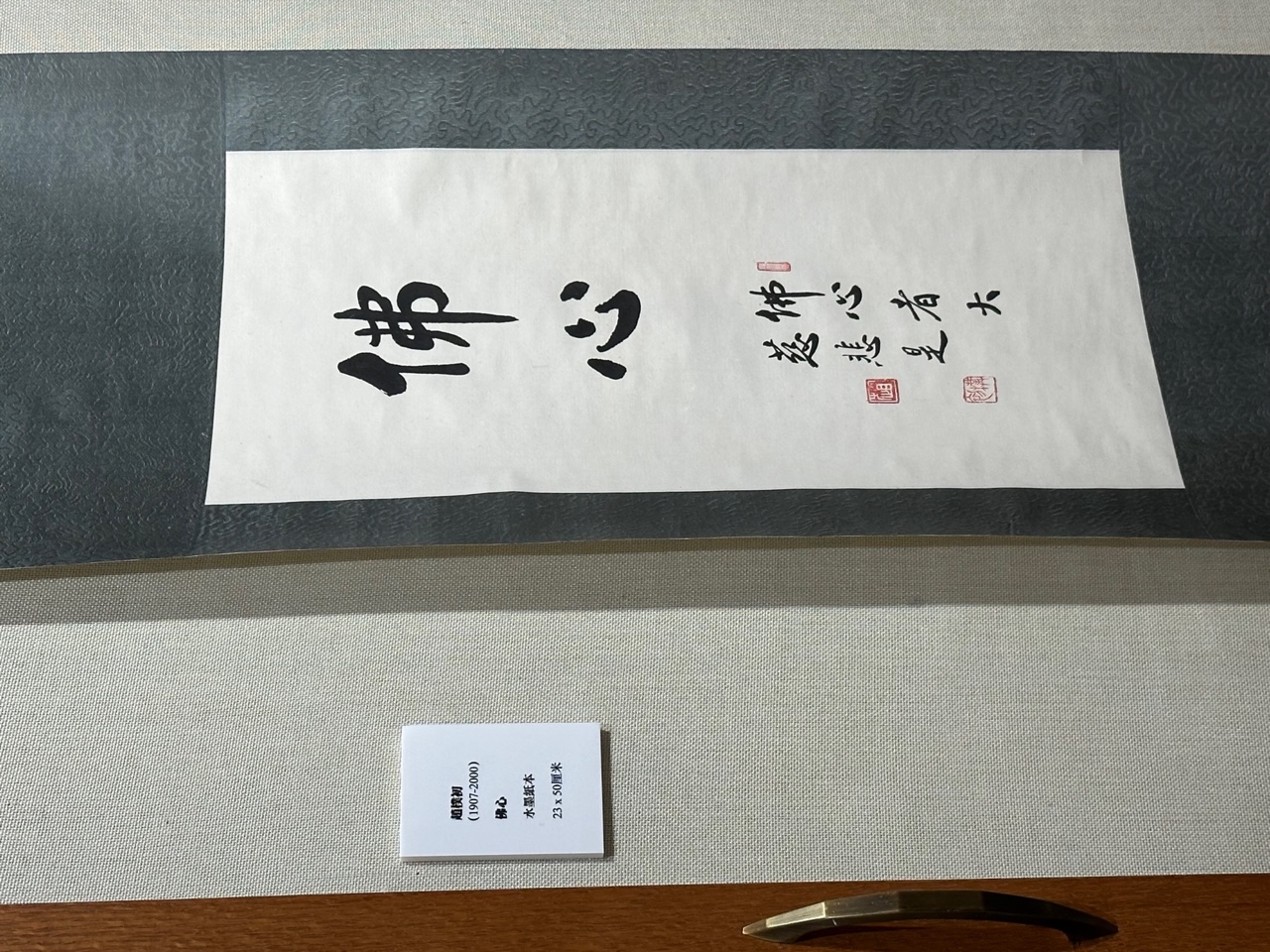

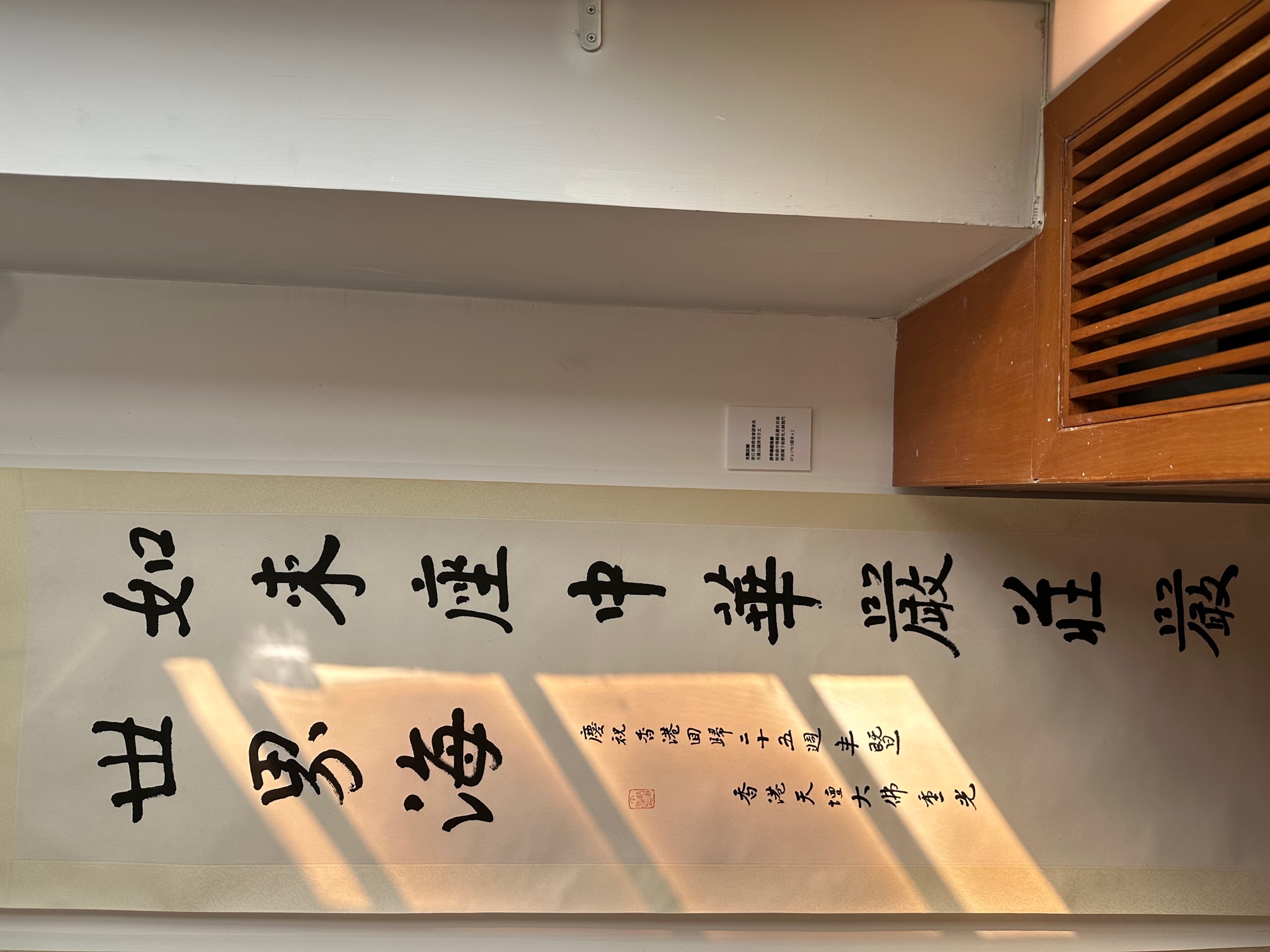

Two of my favorite works from this section are “Buddha’s Heart” by Zhao Puchu (1907–2000), who still remains the most prominent example of lay Buddhist leadership in modern China, and Ven. Yunguan’s calligraphic work “Rúlái zuò zhōnghuá yán zhuāngyán shìjiè hǎi” (如來座中華嚴莊嚴世界海), in what seems to be a reference to the Avatamsaka Sutra, the scripture closest to my heart.

The exhibition signifies the contributors’ blessings to Hong Kong and a profound wish: May art and letters purify our minds and bring loving-kindness, compassion and wisdom to our great city.

Officiating guests included but was not limited to:

– Chen Zetao, deputy director-general of the Coordination Department of the Hong Kong Liaison Office

– Elsie Leung, past deputy director of HKSAR Basic Law Committee of Standing Committee of National People’s Congress

– Choy So-yuk, Hong Kong delegate to the National People’s Congress

– Chan Kin-por, non-official member of the HKSAR Executive Council

– Chan Han-pan, LegCo member

– Venerable Kuanyun, president of the Hong Kong Buddhist Association

– Ven. Jingyin

– Professor Lee Chack-fan, management commitment chairman of Jao Tsung-I Academy