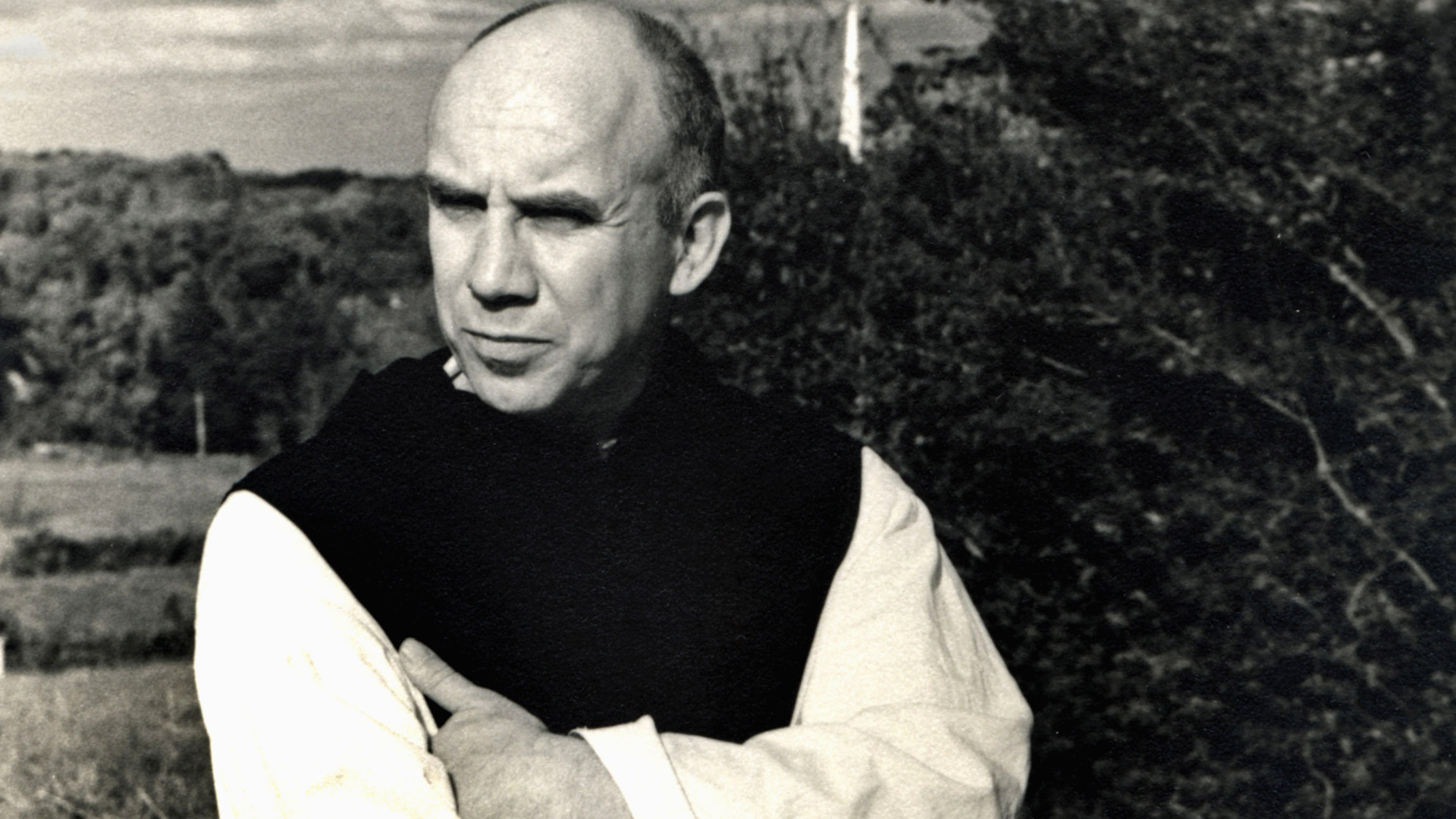

My colleague Justin Whitaker has just published news about the 50th anniversary of the Catholic monk and writer Thomas Merton. It is no surprise that Buddhists have joined Christians in commemorating his life.

I admired Merton to the point of making his work one half of my BA thesis, which was a Buddhist-Christian dialogue between him and Buddhist philosopher Shantideva. Merton operated at the crossroads of a free-form essayist, poet, and commentator and of a liberation theologian, even if not in the Latin American mould. He was certainly anti-imperial: anti-racism, anti-Vietnam War, anti-those who hated Thich Nhat Hanh , and anti-the forces that, in his view, contributed to ossifying theologies within the Roman Catholic Church, of which he was a Trappist member.

He was a far from perfect man, and there remain both Buddhist and Christian thinkers who are cautious of his interfaith overtures in Asia. My own attitude has always been to take him at his word, in good faith. He wasn’t a closet Buddhist on the verge of abandoning Catholicism if he stayed in Sri Lanka a bit longer. Nor was he trying to appropriate Zen in the condescending, guilt-assuaging style that some Catholics felt Vatican II permitted.

It is important to keep in mind that Vatican II, as both a historical testament to the post-World War II and postcolonial world, and a theological document taking seriously the existence of non-Catholic faiths that God didn’t seem intent on wiping out, influenced Merton deeply, and it’s through this lens that I think we come closest to a “Mertonian theology” – a theology of the problematic, which extends to one’s inner self as well: Merton found the world, himself included, problematic.

He struggled, and critics and admirers alike discerned a restless vexation in him, despite the stillness of the cloister. He admitted he couldn’t resist writing, despite his monastic priorities. Yet like a grit of sand in an oyster, his faults and the faults he found with the world led him to organically develop a pearl of a collection of writings which inspires Christians and Buddhists alike today. Much of his writing, especially on the ailments of the modern world (and this was decades ago), ring true today. For any spiritual seeker, that means something, both historically and theologically.

“We stumble and fall constantly even when we are most enlightened. But when we are in true spiritual darkness, we do not even know that we have fallen.”