By Belén Boville

This interview was originally published in August 2023 on Buddhistdoor en Español.

He has improvised a workshop in the Temple of Shorin-ji, the Temple of Awakening, at the foot of the Almanzor peak, in the Sierra de Gredos, under the oak trees of the Mediterranean forest. His name is Takuo Hasegawa. He is the most outstanding Buddhist woodcarver in Japan.

After the first zazen of the morning and the Guenmai, the ceremonial soup recited with the Bussho Kapila, Takuo organizes the burins, the gouges and the wooden pieces that will become small buddhas. The first rays of sunlight weave their sparkles among the leaves and the students take their places on the mat in silence, waiting for the teacher’s “gassho,” the greeting that begins the sculpture workshop.

Takuo Hasegawa is a Japanese sculptor and Zen monk. He was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1983, the son of a carpenter. In 2002 he abandoned his university studies to travel and learn firsthand what was happening in Afghanistan after the attack on the Twin Towers. He then embarked on a journey that took him backpacking for 8 years through Europe and North Africa, then South America, the Middle East, Asia and Japan. His love of nature and forests has led him to direct an international NGO for the protection of forests. This interview shows the depth and beauty of his work and a practical philosophy, zazen, that permeates every moment of his life and work.

Buddhistdoor Global (BDG): How have these journeys influenced you in your approach to the philosophy of Zen?

Takuo Hasegawa (TK): When I was a teenager, despite living in a clean and safe country like Japan, where my life was largely problem-free, I had a nervous personality and lost someone I was close to me. Setting out on my first journey, I was interested in self-discovery, which is to say I wanted to study and know myself more deeply. At this time, I encountered many problems people faced in their lives, for many of whom their biggest challenge was merely to survive in the world.

Zen Master Dogen said that to study Buddhism is to study yourself, and to study yourself is to forget yourself, and to forget yourself is to be actualized by the world. There are many Buddhist sects in Japan and around the world, and many religious groups, and even sects within Buddhism, that compete with or are opposed to each other in different ways, but Zen Buddhism takes the approach that Dogen espoused.

On my journeys I encountered material differences between people and between countries, and I noticed that people were often happier in poorer countries, and of course people sometimes experienced terrible sickness or deprivation. It’s very difficult to find a balance in one’s path to happiness when one’s circumstances are challenging. I realized that it’s pointless to compare one’s life with other people’s because everyone values life differently. I learned to focus on the interiority of human experience rather than on external things, which are only trappings. Buddhism helped me; I read many Buddhist sutras and books on Buddhism and learned that the historical Buddha was a real human; he wasn’t perfect, and he spent time on his own journey studying himself vis-à-vis the world around him. In my study of his life, I found a good friend and a good teacher. I found acceptance in his life’s example as well as in his teachings. And in the connection between nature and human existence, and in the nature of suffering, I learned a great deal, too.

I also encountered dualism in many forms: nature/human nature, ego/non-ego, mind/body, materialism/spirituality, the rich/the poor, good/evil, and others, too. But my own philosophic concerns center on matters beyond duality and non-attachment. I’ve always been interested in what a human being is, and in exploring this I find value in Buddhism’s approach to non-duality and non-attachment. On my journeys, I went from being a very cerebral person to someone who is fully aware of his body and centered on his breathing. I met my physical, Buddhist self and learned to connect myself to the natural environment.

I also learned to recognize and overcome the nihilistic part of myself, which was a big shock to me when I first encountered it. Without overcoming nihilism, you cannot free yourself from despair. One time, in Ireland before I met Zen yet, I felt on the verge of enlightenment. I was walking through a small village in the west side of the country, seeking to discover myself, to find the value of my life and how to live in this world. On a street corner, I felt myself change in a fundamental way, and though the experience is hard to articulate, I can say that it marked the beginning of an interior transformation that helped me overcome my nervousness and my tendency to overthink. I still remember that moment, which was immediately life-changing. I can’t say that it was satori, but it was the most significant and enlightening moment of my life until now. After that, I began reading DT Suzuki, and his writings clarified certain issues for me and helped me develop a more Zen Buddhist mind, and also made me want to learn more about Zen.

After returning from his travels, he began his spiritual quest. Along the way he had become acquainted with Suzuki’s work and teachings, so he turned to Soto Zen Buddhism. In 2010 he wanted to become a monk and went to the Soto Zen Gyokuden-in temple and was told by his master that it was not necessary to become a monk, that he should practice in the social world as a bodhisattva, and he indicated to him that his path was in Buddhist statue sculpture. It was then that he was apprenticed to Shomyo Fukui, the traditional Japanese Buddhist sculptor, with whom he lived in his house-workshop for three years. Shomyo Fukui, in turn, had been taught by Eri Sohei, who in turn had been taught by other masters, thus prolonging an art and tradition considered sacred.

BDG: The figure of the Master is essential in Japanese culture and also in Zen Buddhism. What is it like to be apprenticed to a master sculptor?

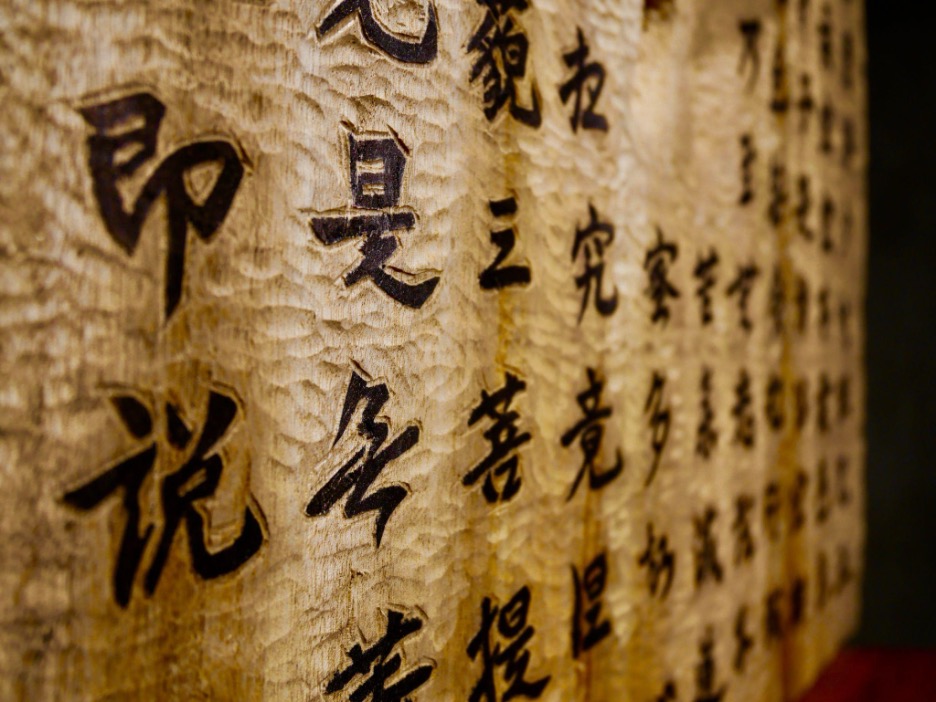

TK: I was born into a carpenter’s family, so I didn’t know if I could develop the skills of a sculptor. I wanted to learn new skills, how to use a chisel and saw and other sculpting tools. Buddhist wood sculpture is a tradition dating back to the 6th century AD, and this busshi embodies wood carving skills as well as culture and art. All together, these strongly connect to Japanese Buddhism. They are also tied to Shintoism, which is more primitive than Buddhism and has millions of gods, and where the connection to nature is more pronounced.

The apprenticeship was to be my foundation for becoming a Buddhist sculptor, but it was also to be the foundation for my life as a Buddhist. There are many ways, to be a Buddhist sculptor, not only through Zen. As Master Dogen said, there’s no need for idolatry, such as by worshipping Buddhist statues, for to study Buddhism means to study oneself. I was very like this way of study.

Being an apprentice is part of an old tradition in Japan, not only to learn specific skills, but also to train your heart and spirit. We receive all of this from the master, and it’s essential to spend time together as if it were a Zen practice. And daily life is practice. That includes speaking, cleaning, cooking, eating, sleeping – everything. Everything we do from one day to the next is practice. My knowledge of this was superficial before my apprenticeship, but over time I absorbed this knowledge, along with my wood carving skills and other cultural learning, and it became an important part of my Zen practice and experience.

BDG: What are the links between Zen Buddhism and the learning of sculpture?

TK: Daily life practice is the central link. Japanese sculpture is a process of uncovering what exists within the wood I’m using, and the goal is to draw out beauty and an image from the individual qualities of a particular type of wood, because every tree is different and every piece of wood has its own individual qualities. I never add anything to a sculpture because I’m simply carving an image from what has existed in the wood from the beginning.

A Buddhist statue looks like a human body, and I focus on the posture of the statue to have it reflect the practice of zazen – the right posture of the shoulders and the right position of the body from the knees to the navel, to the hands in mudra, and even to the ears and eyes and nose. You can notice the difference between Zen Buddhist sculpture and Buddhist sculpture in other countries, Thai, Tibet, and so on, where the shoulders of the statues are much broader, or the chest is more developed. I always asked myself what a Buddhist statue is, but I couldn’t get this answer from my Master. He taught me carving skills more than anything else, but he himself didn’t practice Zen Buddhism or zazen, and he didn’t teach me about Buddhist life. So, I moved to Kanazawa after my apprenticeship and practice zazen and Buddhism more deeply.

BDG: How does your work differ from that of a Western sculptor, a North American or European artist?

TK: I don’t know Western sculpture very deeply, so it’s hard to answer this. But in my sculpting, I’m not only concerned with the materials I work with, but also with the gods that dwell in them. It’s like the word we use for chopsticks in Japanese: hashi, which also means bridge. Hashi is a bridge between the human body and nature. Also, when we talk about gods, or kami in Japanese, we use the word hashira. Hitohashira, futahashira, mihashira means one god, two gods, three gods; and the –ra suffix conveys something coming down from heaven. So, there is significance of this kind in my work, though it has to be said that most Buddhist sculptors, and most Japanese, aren’t aware of the meanings behind these words.

I can find some similarities in Celtic and Native American pre-Christian or non-Christian sculptures. Like a wooden totem pole depicting animal spirits or gods. Celtic paganism has similarities with Shintoism with its gods found in stones and trees, and so on.

Michelangelo made brilliant stone and marble carvings whose beauty and influence over time have never been duplicated. They are unique in human history, and I wonder if he felt like he was uncovering the gods within his material like Buddhist wood sculptors do.

I should add that a Japanese gardener’s approach to his work is not intentional – he doesn’t wish to put an artificial human touch on it. Instead, his intention is for his gardens to look completely natural and free from human interference. One can maybe see the same difference between Japanese Buddhist sculpture and Western sculpture. For Japanese Buddhist sculptors, the idea is to harmonize with nature, not control it, not put our mark on it. It requires skill to show no obvious signs of human effort.

But I don’t want to make clear separations between Japanese and Western sculpture. The feeling that Western sculptors bring to their art may be the same, with a kind of religiosity felt toward one’s materials, a kind of reverence. I want to know more about this, actually, and hope to talk about it one day with Western sculptors.

BDG: Do you play with these symbols in your art, or do you incorporate them into anthropomorphic Buddhas?

TK: Yes, both. I use the symbol of the lotus flower, which is a powerful Buddhist symbol, of course. The lotus grows from mud, but when it blooms it is pure and beautiful. I also make “human-style Buddhas.” My art resembles human-like Buddhas engaged in zazen. But I must be careful that my Buddhist sculptures are not idols. I sometimes portray these figures as sitting on blooming lotus flowers. These symbols and images are commonly used in Japanese Buddhist sculptures, and I use them, too.