By Belén Boville

This interview was originally published in August 2023 on Buddhistdoor en Español.

BDG: Zen art, with its naked naturalness, shows us ku, emptiness, and a philosophical concept, wabi-sabi, transience and impermanence. How is that reflected in what you do?

TK: Some sects like Jōdo-shinshū have very colorful and elaborate art, but Zen art, like mine, is simpler and more subdued. All Buddhist art is based on three Dharma marks or concepts: all existence are impermanent; all phenomena are self-less; and Nirvana is tranquility. Also, Buddhist culture around the world can differ greatly, but Zen art, if I can explain it this way, has five characteristics: simplicity, tranquility, poverty, naturalness, and imperfection. This is where the concept of wabi-sabi comes from.

Tranquility is central to the idea of nirvana and all Buddhist art. Nirvana comes from the words niru (gone) + vana (burning fire) and suggests the extinguishing of the ego. This quietude, this tranquility, is reflected in Buddhist art. So, people who take drugs to experience satori, or enlightenment, are mistaken to think they can reach it that way. Nirvana is a state of tranquility reached by pure, natural means. It means you’ve reached a kind of perfection on your own, from the purity of your own being, and you learn not to close your inner or Buddhist half-eye (like one sees in the Buddha’s image and maintains in zazen) or to shut out any part of the real world. The concept of tranquility is seen in the Buddhist Middle Way, too.

In my carving I only ever use a single piece of wood. If I come across warping of the grain, or knots, or cracks in the wood, I always enjoy accommodating those natural features and never try to fix them. This reflects the importance not only of imperfection but also of impermanence, because the wood was once alive and changing constantly. Humans are the same, containing imperfect beauty, or beauty that includes imperfections. And, of course, beauty is impermanent.

BDG: Besides Buddhist art, religious art and the representation of the Buddhist pantheon, do you create any profane works? Is there a separation between the sacred and the profane in your work?

TK: Zen art reflects daily life, daily concerns. There is no separation between the world of the gods and the daily life of humans; they overlap or intersect. In Zen philosophy, daily life is a miracle – not events like walking on water. There is no need to separate religious experience from the human experience of daily life. Our existence on earth is no different from existence as seen in the Buddhist idea of Pure Land. The earth we live on is already a Pure Land. Even when we try to change ourselves, or try to shape our physical environments like people often do with forests and gardens, we must remember that we already exist on a beautiful and pure land. That is a Buddhist belief that I feel.

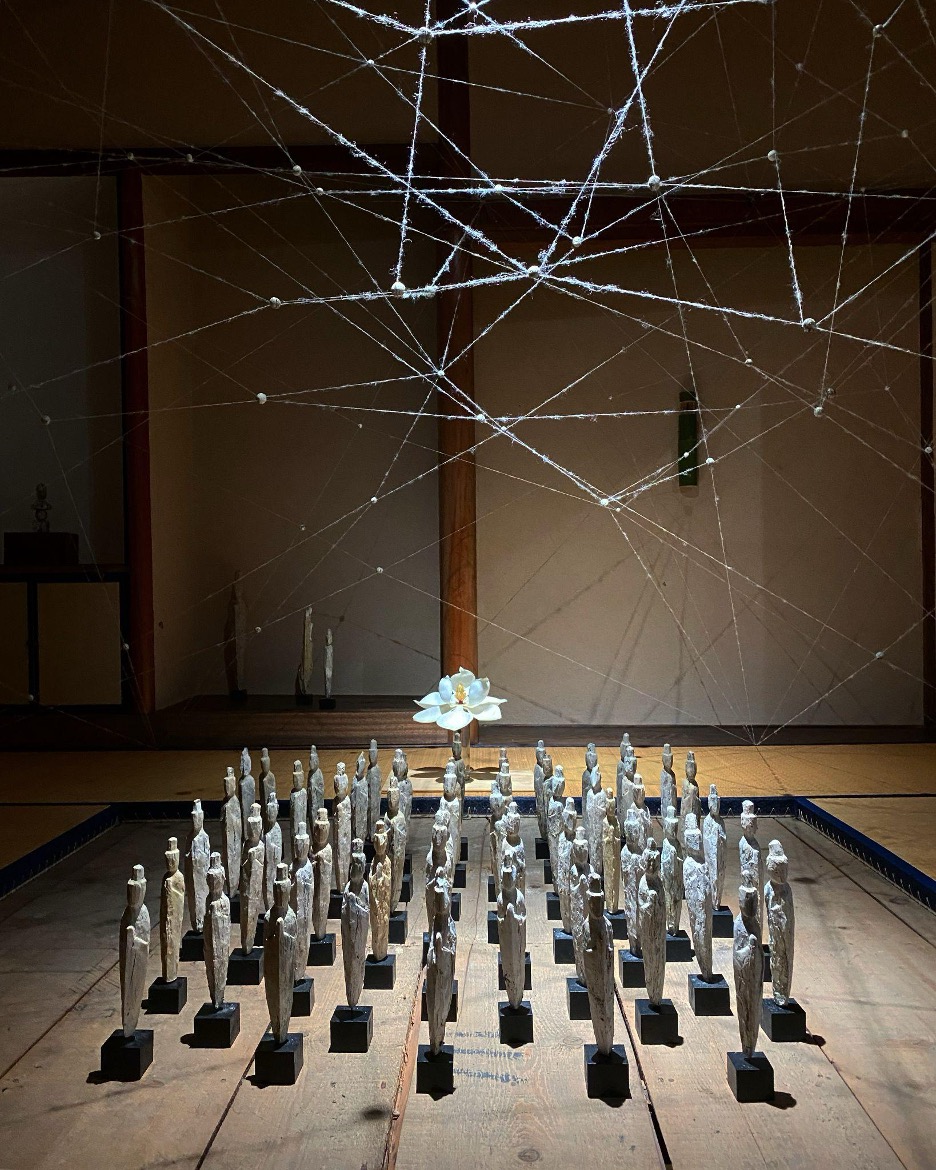

I make my own chopsticks, rice bowls, soup bowls, and those sorts of things, but those are for my daily life and have no religious significance. They are not sacred. But my sculptures all express Buddha. Especially Mahayana Buddha, or Buddha Dharma, and the three characteristics I mentioned earlier: impermanence, no-self, and tranquility. We call these Buddhist works hotoke, and they reflect the force of life and the universe. Hoto means the place where gods come from. And ke means energy or power. That’s how I think about my art, that it reflects the idea of hotoke. It reflects the spirit or energy of Buddha.

BDG: What are the sizes of your works and which is the largest?

TK: My largest work is an 11-faced Buddha carved from a camphor tree from Mt. Hakusan, which is one of the three most sacred mountains in Japan both for Buddhism and Shintoism. This work stands about 250 cm and weighs 800 kg. My normal sculptures, however, are 20-30 cm in height, and sometimes as tall as 70 cm. Most are made from kusunoki, or camphor, a type of tree and wood considered sacred or holy in Japan. The kusunoki is actually the tree where Totoro lives in in the famous Ghibli movie Totoro. In India, incidentally, the sacred wood that Buddhist and Hindu sculptures are made from is sandalwood, but in Japan sandalwood isn’t native, whereas camphor is. The first Buddhist wooden sculptures, made in the 6th century, were almost all made out of camphor.

BDG: What are the temples, museums or public spaces where we can go to see your work?

TK: You can see my work at the Kannon-in Temple in the Higashiyama district of Kanazawa and at the Kanazawa Shrine (Kanazawa Suitengu), near Kanazawa Station. My work also can be seen in rotating exhibitions around Japan. And in my small gallary/izakaya in Kanazawa, called Huni, I have a permanent gallery space displaying my sculptures. And now, I’m offered Buddhist statue Kannon in Shorinji. It can to see the near future in there.

BDG: Does your izakaya also have a sacred character?

TK: Huni doesn’t have a sacred character like a temple or shrine, but as I said, it has an open gallery space featuring Buddhist and Shinto sculptures. It’s a place where people can encounter Zen Buddhist art, as well as reflections of Buddhist art and culture in Japanese daily life. I also host weekly zazen meditation, a Buddhist woodcarving workshop, and regular events that feature seasonal gyohatsu Zen cuisine, tea ceremony, and ikebana flower arrangement.

BDG: What is your role in reforestation and forest restoration? Is it also a sacred and necessary activity?

TK: Forestry products are used for building houses, making charcoal bricks, and many other things, including carving, that are necessary to daily life. But I don’t only want to take from the forest. As the director of IDGA (International Desert Green Association), I also want to give back to and protect the forests. Reforestation and forest-keeping in Mongolia and other places where Buddhism passed through before arriving in Japan are important activities to me, and I enjoy and care deeply about that part of the world – the Silk Road. Neither activity is sacred to me, but I value them both as a kind of social activity. At the same time, I want to understand how nature circles through the stages of growing, being culled or cut down, and re-growing, and what insects and animals and other forms of life contribute to forest growth. There’s so much for me still to learn, and I enjoy that endeavor very much.

BDG: Why, when you finish sculpting a Buddha in Shorinji’s workshop, does it end up burning?

TK: Burning is akin to emptiness. And emptiness is an important practice in Buddhism. You must study yourself and study emptiness to overcome the endless “monkey mind” of wanting more. And because this wanting more is endless, the practice of emptiness needs to be endless, too.

It’s also applicable to wood sculpting. The burning of a finished sculpture is good practice to let go of something we value for its materiality. When a sculpture turns to ash, it scatters and returns to earth. That contributes to the circle of life and connects one thing to another (a phenomenon called engi in Japanese).

BDG: At Shorinji Temple, you have been teaching woodcarving for two years, in the summer of 2022 and in 2023. Will you continue your teaching at Shorinji? What should our readers do to become students of your workshop in Shorinji?

TK: Yes, I plan to continue my teaching at Shorinji! I’m very happy to introduce Buddhist woodcarving to students at Shorinji. It’s my dream as a person and also as a practicing monk to help others make Buddhist sculptures using local wood. Buddhism came from India and is now entrenched in many parts of the world, where the natural conditions are all different. Buddhist statues in Japan come from as far back as the 5th century, and they have developed a great deal since then, spreading to every corner of the country and becoming accessible to everyone. My wish is that one day in European and other western countries and cultures, Buddhist sculpture will bloom and spread in a similar way.