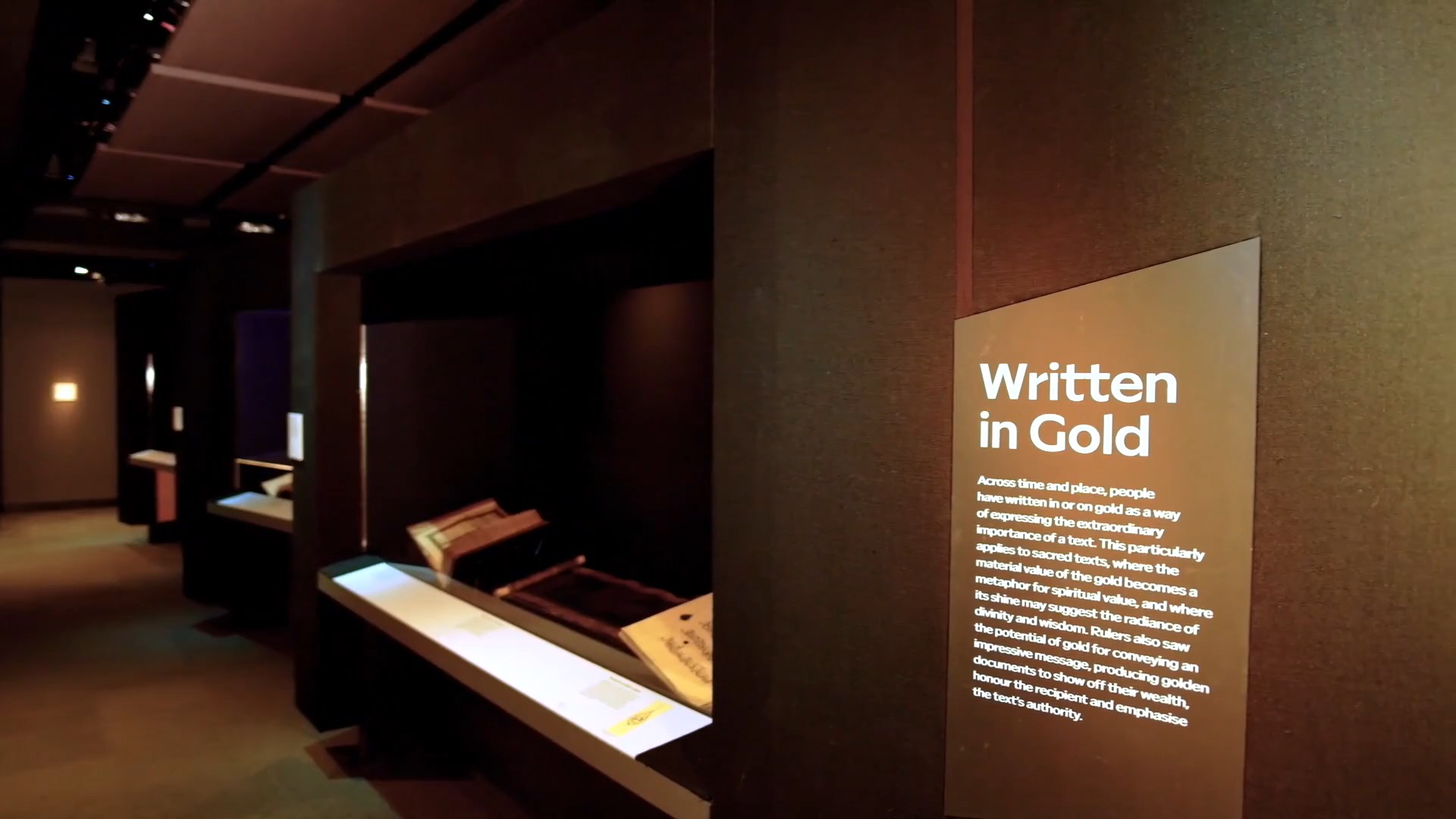

In lieu of physically attending a private viewing of The British Library’s “GOLD: 50 spectacular manuscripts from around the world,” I was privileged to enjoy a rich and informative virtual tour of the exhibit in the early hours of the Hong Kong morning with others that could not be in London this month. Gold is grandeur. Gold is glory. These manuscripts that variously incorporate gold into their pages, bindings, or covers are on display from 20 May to 2 October. They communicate power, magnificence, holiness, and sumptuousness. They are letters, religious texts, legal documents like treaties and records that share a consistent yet diverse bookmaking technique. Many of the objects would have been owned only by royalty or extremely wealthy individuals, and now these priceless texts are open to the public.

After an introduction from Dame Carol Black, Dr. Alixe Bovey, chair of the Courtauld Institute, hosted the tour and a Q&A with the curators of the exhibit: Eleanor Jackson, Annabel Gallop, and Kathleen Doyle. Dr. Jackson is Curator of Illuminated Manuscripts, Dr. Doyle is Lead Curator of Illuminated Manuscripts, and Dr. Gallop is Lead Curator of Southeast Asia. Together, in the face of an unprecedented pandemic, the curators put together an incredible range of 50 illuminated masterpieces from 20 countries in 17 languages.

My interest was obviously in the Buddhist items, although there are superb and priceless texts from other faith traditions. My favorite Christian example was a Benedictional (a book of benedictions) from Winchester “with a fine depiction of St Etheldreda, the royal nun, with a golden habit and lily.” (Evening Standard) Gold, aside from expressing power, also indicated sacrality in its brilliance, rarity, and interactions with light, one aspect of physicality that the virtual tour had to adapt to by moving the camera over the shining gold.

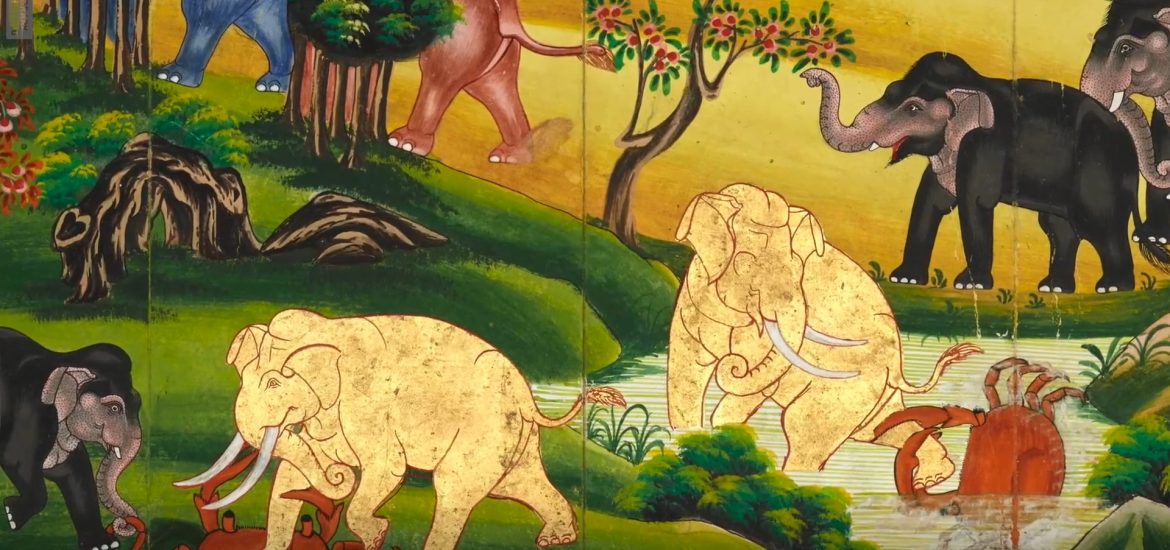

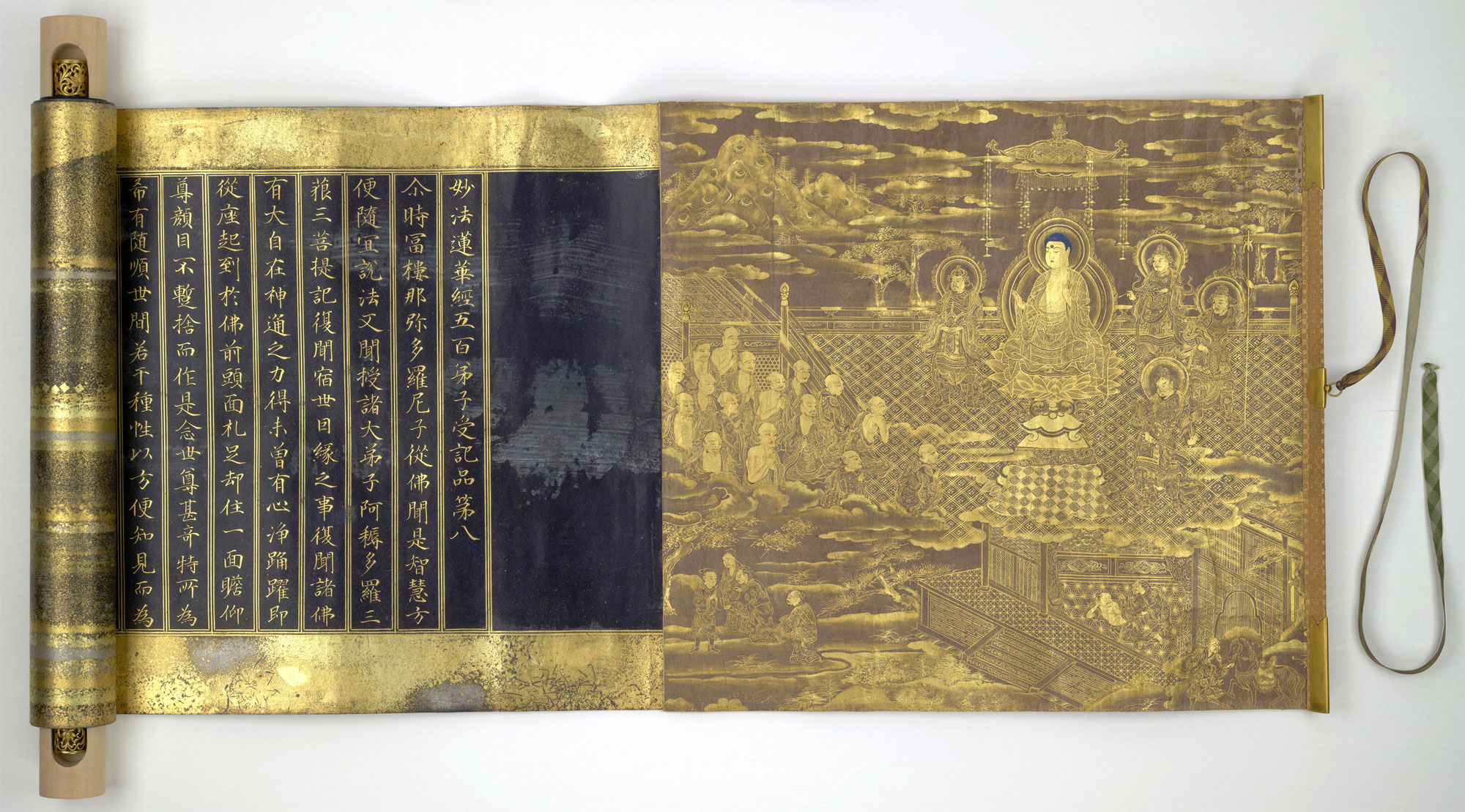

The oldest Buddhist item, at least the oldest one made with paper, is the Lotus Sutra scroll (MS 16624, f.2r) produced in 1636, in the reign of Edo emperor Go-Mizunoo (1596–1680). The other items are relatively recent, dating back to the 1800s. From Myanmar we have a Burmese manuscript, Tikanipat (Or 4542/B, f. 111r), in which gold is used to identify the future Buddha, the Bodhisattva, in various Jatakas (stories of the Buddha’s lives). In one segment, the future Buddha (in other words, the Bodhisattva) is reborn as an elephant. His compatriots are hounded by a giant crab living in a lake close to the herd. The crab seizes the Bodhisattva in his claws and they engage in a high-stakes fight. Only after the Bodhisattva’s elephant mate makes peace with the crab by flattering and complimenting it, does the crab end the struggle and release him. (The British Library)

A gilded and lacquered book cover book cover in Thai and Khmer script (Or 15257) depicts the celestial forest of the Himavanta realm. This item, “Buddhist texts and Phra Malai,” was made with lai rot nam, “design washed with water.” As a blog post on The British Library’s website notes: “Thick mulberry paper was covered with layers of black lacquer, a pattern was traced, areas to remain black were painted with a natural gum, and gold leaf was applied to the whole surface. The next day the gum was removed with water to reveal the intricate gold design.” (The British Library)

Dr. Gallop, in the Q&A session, answered a question I raised about the relative contemporaneousness of the Buddhist gold paper manuscripts in Southeast Asia. She said that in the Southeast Asian world, Buddhist paper manuscripts of gold only date from the 17th Century onwards. Paper was not prone to survival in regions that today constitute modern-day Thailand, Cambodia, and Myanmar. Nevertheless, The British Library does have an exception: the 5th century-era Maunggan gold plates, written in Pali in the Pyu script and cast in exquisite gold leaf. Easily one of the oldest surviving Buddhist texts from Southeast Asia, these gold plates would have been interred in a stupa, the Theravada structure containing the presence of the Buddha (often through a relic).

“The problem with gold,” noted Dr. Gallop, “is that gold is so versatile; that most gold manuscripts or inscriptions were very quickly melted down and reused for other things. Interestingly enough, there’s an inverse proportion [between quantities of gold in manuscripts and their survivability]; gold used in smaller quantities in books will probably survive for many centuries, but the ultimate gold manuscripts are very, very susceptible to being recycled and being valued more for their material rather than their words.”

In Dr. Gallop’s answer is a dual irony, and it is not only that texts that used gold more sparingly have usually lasted longer than those made entirely from the element. Gold leaves thinned out into foils, or as a powder for painting over fragile paper or throughout multiple pages, are much harder to extract than a thick gold text that can simply be melted down. The latter, products of extravagant ostentatiousness and vanity, probably left itself wide open to tempting fate and human greed. There is also the irony that religious manuscripts using gold to express the transcendence, beauty, and majesty of a sacred teaching or story should risk the same materialistic, greedy eye that holds no respect for the words in the text, and only wants the components of the text. Gold is magnificent, desirable, and splendid, as this exhibit estimably demonstrates, but it is only the vehicle for the sacred word, and for the faithful, the word (buddhavacana) will always matter more.