In a letter dated 6 January to Monsignor Paglia for this month’s 25th anniversary of the Pontifical Academy for Life (which was founded in 1994), Pope Francis noted: “Relying on results obtained from physics, genetics and neuroscience, as well as on increasingly powerful computing capabilities, profound interventions on living organisms are now possible . . . Even the human body is subject to interventions capable of modifying not only its functions and capabilities, but also its ways of relating on personal and societal levels, with the result that it is increasingly exposed to market forces.” (Vatican Insider)

While this is admittedly representative of a Catholic view, I personally feel that it is quite valid. The explosion in popularity of “popular science” has, despite what the snobs say, been instrumental in helping to educate the wider public in scientific literacy. However, we know very little about the mechanisms of the vast majority of scientific breakthroughs. On the whole, we are so ignorant (simply because it is happening so fast) about the processes involved with this rising world of high tech that we almost don’t see discussing its ethics as particularly desirable or helpful, let alone have a broader picture of the consequences.

Take Facebook, for example, which I remember signing up innocently enough for in 2007, as a student who wanted to keep up with his college peers. Not even the most farsighted tech journalist or Silicon Valley executive could have foreseen how the literal fates of entire political movements rest in Facebook’s hands, and how the reach of so much media (from websites to magazines to newspapers) now depends on friendly algorithms on social media platforms. See how photo-sharing app Instagram (also owned by Facebook), which pushes a concept that would have seemed like a silly gimmick years ago, is in the crosshairs of policymakers as a real source of mass insecurity and unhappiness among young people. Social media has transformed a large part of how we, as human beings, circulate information and share news, and even socially interact, at an everyday level.

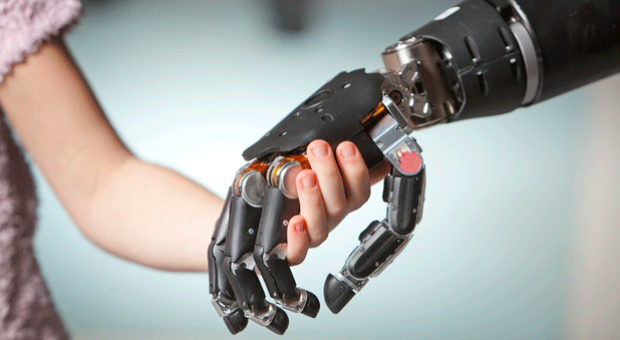

Simply expand this thought to so many other industries, from genetic engineering to robotics to climate science. The scale of the pace of change is staggering, and holds so many implications for humanity’s future that many philosophers and ethicists are convinced that we need an entirely revised paradigm of our relationship with technology in order to know right from wrong.

Thanks to affinities between Buddhist meditation and psychology and neuroscientific research, Buddhist-scientific dialogue has been framed in an optimistic light over the past few decades. I would like to offer not necessarily a contrarian view, but a slightly more cautious one. Ultimately, how might technology tempt us to deviate from how we currently exist as human beings altogether? Will transhumanism win out? Will our mortal limitations become seen as hindrances to a rapacious attitude of “more is never enough” rather than reminders of our samsaric condition, that we are and need far more than the “materiality” of the universe?

How can we deploy science and futuristic technology in the Buddhist way: to pull our planet back from ecological decline and civilizational calamity, rather than accelerate these worrying trends?

To tackle the existential questions that are already unfolding before us, we need bold creativity and imagination. Consider the ideas of Father Benanti of the Pontifical Academy for Life, who noted: “In an age marked by a secular culture in which religion has less power over pop culture, science fiction is the place where those myths that animate this culture reside. That is, science fiction narratives are those places where a sort of pseudo-religious thought finds a very fruitful environment and collects, orients and expresses desires, fears, hopes and expectations about the future of our generation. I would reverse the question: I would say we look at the world of science fiction and its mainstream narratives, because there we find the experience in the hearts of our contemporaries. Explaining what is happening is an important question for philosophers, theologians, and even social scientists.” (La Stampa)

In other words, it’s no longer (and perhaps never has been) a simple religion versus science debate. All parties need to think seriously about the human story that we are all writing together in a new era of high tech and scientific advancement. That is why, this year in 2019, our editorial team will soon be turning a sharper focus on the relationship between Buddhism and tech: specifically, how Buddhism and science (and Buddhist scientists) might build a better world together and stave off the greatest perils currently threatening human survival . . . and more importantly, how the sacred dignity of the human being as a spiritual animal can be honored even as we engage more with cybernetics and robotics, and could well be unrecognizable to our ancestors in a few decades or even years.

I hope you look forward to these upcoming developments, and that they can provide perspective with enough answers to encourage further exploration . . . yet not so many answers as to appear conceited and contrived.

See more

The Pope: “Life today is being brutally violated by profit and technology” (Vatican Insider)

The Vatican: “In the age of robots we must invent new ethical and legal criteria” (La Stampa)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Buddhistdoor View: Irreversible Climate Change—One Decade Left

To Keep or Not to Keep? Mortality, Humanity, and Transhumanism