Welcome to our series of conversations with participating speakers at this year’s Tung Lin Kok Yuen International Conference – Buddhist Canons: In Search of a Theoretical Foundation for a Wisdom-oriented Education (27–28 November 2021). In each blog post, I talk to keynote speakers and paper presenters about their subject at this conference.

This conference has concluded.

Knowledge tied to or freed from identity? Epistemic reflections through the prism of the early Buddhist teachings

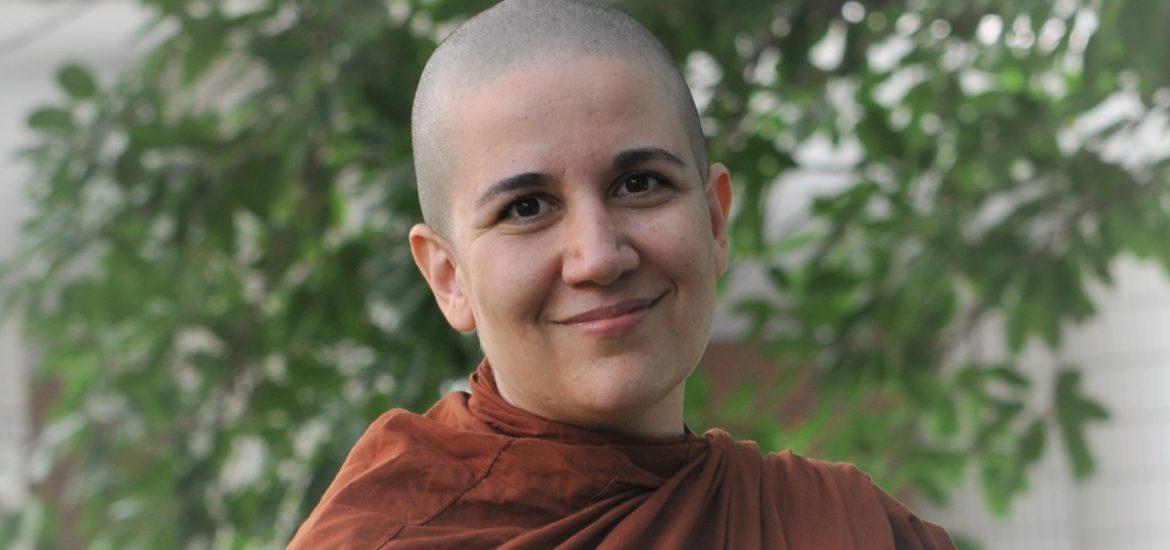

Bhikkhuni Dhammadinna was born in Italy in 1980 and went forth in Sri Lanka in 2012. She studied Indology, Indo-Iranian philology and Tibetology at the University of Naples of Oriental Studies, at the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University in Tokyo and at the Institute for Research in Humanities of Kyoto University. Dhammadinna received her doctorate in 2010 with a dissertation on the Khotanese “Book of Zambasta” and the formative phases of Mahayana and bodhisattva ideology in Khotan in the fifth and sixth centuries. Her main research interests are the early Buddhist discourses and Vinaya texts, and the development of the theories, practices and ideologies of Buddhist soteriologies and meditative traditions. She is a visiting associate research professor at, and the director of, the Department of Buddhist Studies of the Dharma Drum Institute of Liberal Arts in Taiwan. In addition to her academic contribution, Bhikkhuni Dhammadinna regularly teaches meditation. She is now based in Italy most of the time, where she lives a secluded lifestyle.

Buddhistdoor Global (BDG): Venerable, can you please describe the general theme and ideas in your lecture?

Bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā (BD): My paper looks into how notions of experience and conditional construction of identity and self-conceit, read through the prism of the early Buddhist teachings and transmitted in the early Buddhist discourses, can inform and enter into dialogue with the postmodern foregrounding of the person’s or knower’s deeply felt lived experience as an epistemic absolute.

The Buddha’s liberating knowledge, the Buddha’s awakening, reportedly came about as a result of having seen through the fabrication of conditioned experience that results in the construction of identity (our ego, in short) and in the identification with such a process. Experienced conditioned by what? By craving (taṇhā in Pali, tṛṣṇā in Sanskrit) and ignorance (avijjā in Pali, avidyā in Sanskrit). So, having penetrated the way conditioned experiences and construction of identity are brought about by the twin agencies of craving and ignorance, according to the early discourses the Buddha was able to understand how conditioned experience comes into being and how one comes to be identified with one’s own sense of identity. We have the construction of experience, which is a cognitive fact, and further identification with this as a further constructed identity, which is another self-referential layer on top of having conditionally arisen in the present moment.

As the arahant bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā (yes, I am her namesake) explained in a memorable exposition, in the Buddha’s teaching it is the so-called five aggregates of clinging (Pali upādānakkhandha, Sanskrit upādānaskandha) that are reckoned as “identity.” The five are bodily form, feeling tone, conceptual identification, volitional formations, and consciousness. These stand for the “where,” the “how,” the “what,” the “what for,” and the “who” of subjective experience. The arising of identity is due to delight and attachment in relation to future becoming – that is, the continuation of such experience – together with craving that relishes here and there. The cessation of such fabricated cluster of identity is accomplished through the removal of delight and attachment in relation to future becoming and craving, through their complete renunciation, exhaustion, fading away, cessation, and pacification. Cessation takes place through penetrative knowledge (in the sense of liberating insight), so that for such kind of “knowledge” to happen, one has to depart from any clinging to and identification with experience (defined here by way of the five aggregates of clinging). Such knowledge is by definition “untied” from identity as it comes about through the cessation of identity.

The knowledge I am talking about here is soteriologically-informed, soteriologically-relevant, and soteriologically-oriented throughout. It is the type of inner knowledge that is informed by the notion of the Buddha’s liberation, which stands for total freedom from defilements, being the type of knowledge that is relevant to the attainment of the same inner condition by others, and the type of knowledge that is aligned to that end.

Instead, what I referred to as the post-modern epistemic absolute is based on the belief that knowledge is intrinsically tied to identity. And consequently this belief embraces positionality and standpoint theories as valid theoretical and practical foundations for personal and communal education, or cultivation. These beliefs come to percolate contemporary Buddhist discourse more and more. This happens not just with the academic study of Buddhism, but also in Buddhist practice, the practice of the Dharma, in Buddhist communities.

BDG: Could you say more on “positionality” and “standpoint theories”?

BD: This postmodern renegotiation of identity and identification is very interesting, because it elevates the epistemic status of personal experience as shaped by the specifics – and the idiosyncrasies – of the lived experience of different identity groups, who are differently positioned in society and therefore see different aspects of it. There is a radical scepticism that knowledge can be objectively or universally true. This leads to the conviction that the legitimate basis for knowledge is not the methodology through which evidence is approached, but rather identity-based “standpoints” and multiple “ways of knowing.” Their value does not depend on seeing through how identity is constructed but rather on the person’s gender, race, sexuality, geography, social condition, and so on.

The idea is that one’s identity and position in society validates how one comes to knowledge. So knowledge is always “situated,” that is, it results from one’s particular internal, external, and internal-external or relational “standpoint” in society. Here with internal, external, and internal-external I refer to the three fundamental dimensions of subjective experience as spelled out in the early Buddhist teachings on mindfulness: myself (internally), the other or others (externally), and the relational self-other field (internally-externally). Mindfulness can be established in relation to all three dimensions; its application to all three dimensions together yields the most effective potential for individual and societal transformation.

Often this amounts to one’s membership in intersecting identity groups. The net result is that objective truth is not available and that knowledge is inescapably tied to identity. Identity is in turn shaped by social and ideological power (or lack thereof, or struggles to assert it). As a consequence, knowledge itself is tied to the discourse that the interplay of knowledge and power are seen to co-create (that is, which group(s) I belong to and their social positions in relation to epistemic power). Here, for example, belonging to a minority or marginalised group grants special access to truth, in that it gives the person a unique epistemic insight, without much room left for the categories of universality and individuality that have shaped humanity collectively through the ages. So, from an early Buddhist perspective, knowledge becomes inescapably tied to my experience of the five aggregates of clinging. But these are biased due to the very presence of clinging and identitarian investment into them by way of relishing them and thus a conceit of self/selves arises.

The logical fallacy of standpoint theory is obvious: it presupposes that individuals who occupy the same identities built on their social positions (such as race, age, ability status gender, sex, sexuality, or health) must share the same subjective experiences of being in the world by way of dominance and oppression, provided that they are sufficiently and correctly able to understand them. (Occupying more than one such positions is defined as “intersectionality.”). Such placements intrinsically lead to interpreting personal experience in roughly the same ways (to the extent that the person is aware of their positionality). These experiences supposedly provide me with a more (or the sole) complete picture, which is intrinsically authoritative. From this follows that one’s positioning determines what can be known and by whom it can be known, and what cannot be known by whom. Typically, the socially underprivileged and oppressed are assigned an epistemic superiority, grounded in their insight into both their own position and the power dynamics that generate it, whereas the socially privileged and dominant are assigned a place of epistemic inferiority attributed to lack of insight into the biases of their own lived privilege and into that of the lives of the oppressed. Personally, as a European fully ordained female monastic (bhikkhunī), whose very “right to exist” is called into question by a large section of the Theravāda monastic institution, and who no doubt faces discrimination due to institutional androcentrism and ascetic misogyny among other ideologies, I do not believe nor feel that my existential predicament is by definition inaccessible to other human beings who do not share exactly the same “experience” as “me”. In fact, I could add several layers to characterize the “intersectionality” of my subjective experience and the discrimination I am confronted with as I find myself in different contexts. But I do not reckon myself as being defined in terms of such predicament, or multiple predicament, nor do I wish to be reckoned based on that, let alone reduced to that or be epistemically as well existentially imprisoned into that. And by all means we need to avoid narrowing our space to the point of egotistically focusing on the felt sense of our own difficulties and losing the capacity to make space for the other.

Now, lest I be misunderstood, there is indeed a pressing need to support and empower the socially underprivileged and oppressed, just as there is a similarly pressing need for the socially privileged and dominant to become aware of their privileges and patterns of domination. Nevertheless, I feel that, if taken to the extreme, these trends make us prisoners of identity rather than enabling an understanding of it. And what to say of the supposed epistemic “fluency” one is supposed to exhibit in becoming adept at constantly redefining my many identities and self-positions, what to say of all the identity politics and relishing them as yet another performative function of identity-building and delighting therein? So I become more inescapably tied to my experience of the five aggregates of clinging and fuel them with further raw material. But they are biased due to the very presence of clinging and identitarian investment into them by way of relishing them in the first place. From an early Buddhist perspective, this cannot lead me onwards on the path to freedom from defilements.

In fact, the Buddha is on record for pointing to the fundamental dimension of experience represented by contact by way of the six sense bases (Pali phassa, Sanskrit sparśa) as “standpoints” or “grounds” (Pali vatthu, Sanskrit vastu) for the establishment of self-views – including lofty meditative attainments, cosmological and philosophical positions. Contact is none other than the baseline for the arising of personal experience. By pinpointing even the barest form of experience (contact followed by feeling tone, vedanā) as that which leads to the arising of a view and is responsible for the arising of self-positionality, the early Buddhist teachings certainly do not encourage the pursuit of standpoint theory.

BDG: So, is it accurate to say that the Buddha has something to say about subjectivity since he taught about the experience of dismantling identity and identification with constructed identity?

BD: It is a radical act of deconstruction of constructed identity. According to the Buddha as described in the early discourses, we have the potential to come to an assessment of our own subjective experience on objective grounds. So there definitely is priority given to first-person experience, and at the same time there is a possibility, according to the early Buddhist teachings, to understand first-person experience and subjective experience in a way which is more “objective.”

Why more “objective?” Because it is no longer reified on a self-referential basis by dint of craving and ignorance. When I stop reifying my experience and identifying with my experience, a more objective knowledge of the way my subjective experience comes into being becomes possible. And this runs counter to the idea of “lived experience” being unique, and not accessible by people of different “identity.” Taken to the extreme, this position implies that the Buddha’s discovery of the cause of existential dukkha (Pali; Sanskrit duḥkha) that is true for all beings becomes simply meaningless and the path to emancipation from it inapplicable. This is quite an important point.

I think because there definitely is an act of truth based on first-person experience, and there is a claim to truth based on first-person experience on the part of the Buddha, there is a possibility that everyone else can arrive at the same experience of truth in relation to their own first-person experience by following the early Buddhist path to emancipation. This emancipation is freedom from craving and ignorance, which create cognitive biases, emotional biases, and ethical biases (whereby our first-person experience is misconstrued).

There is this constant interplay between first-person experience and the possibility that the same is verified by the third-person experience of someone else in their own first-person experience. So, there is certainly absolute priority given to subjective experience in the Buddha’s teachings.

BDG: So how do the early discourses convey this notion of liberated experience?

BD: Essentially, we are left with the same terminology that is used in the early Buddhist discourses to describe subjective experience (āyatana, which here stands for experiential domain or experiential base, or sphere of experience; and contact, sparśa in Sanskrit, phassa in Pali, which is contact by way of the six sense bases).

For example, consider the experience of Nirvana described as an āyatana, that is to say, as an experiential domain or sphere. It is said that it is possible to contact the cessation of experience, to experientially contact Nirvana with one’s own being. This goes to show that, once the task of deconstructing constructed experience was accomplished (2,500 or so years ago!), no need was felt to posit a whole new discourse to establish an ad hoc language for this new domain of liberated experience.

The Buddha apparently proposed no new rhetoric of personal experience here. Even the highest form of personal direct experience, the experience of full awakening or Nirvana (which basically amounts to an experience of cessation of fabricated subjectivity), does not need to build a whole new set of terminology to account for these experiences of coming out of identification with conditioned experience.

We can see that the Buddha is shown to have no problems in using the first-person pronoun in his discourses. When describing his recollection of past lives, he is on record as using the first person: “I” was of such-and-such a name, and “I” was born into such-and-such a clan. Or, again in the first person, “I” awoke to unsurpassed perfect awakening, I am one who has become cool, become extinguished, I have understood it all, and so on.

The early Buddhist arahants are also seen speaking in the same way. For example, there is a fully awakened nun, Kisā Gotamī, who refers to herself as “I am”: “I am one who has cut out the dart, laid down the burden and done what had to be to be done.” The critical distinction is that these self-referential terms, like “I” or “mine,” are used to refer to completely freed and completely free subjective experience. This does not conflict with the not-self teaching of anattā or with emptiness. Rather, thanks to the full realisation of not-self and emptiness, such terms can be held lightly without any reification and without any conceit or clinging.

BDG: Why are the Buddha and fully awakened beings fully entitled to speak in the first person without any risk of misrepresentation or of biased representation?

BD: Because they have eradicated conceit (Pali and Sanskrit māna), they have eradicated conceivings, imaginings, building self-images and all selfing, self-referencing. They have overcome all of these possibilities of positioning of oneself in relationship to reality under the affect of craving and ignorance. There is no more of this possibility, and so language and first-person experience is freed, and absolutely free, from ignorance and from craving, and it is absolutely not problematic, from an epistemological point of view, and it can be used in a very fluid way. No more “selfies” to be taken, as it were.

Māna is basic conceit, the notion of “I am” imbued by craving. Essentially, conceit equals the notion “I am” (asmī ti mānagatam etaṃ). So, this very sense of the notion “I am” stands for conceit. But there is no problem in saying I am this or I am that, speaking in the first person, or speaking of others in the third person, precisely because once this problematic relationship with language, with conventions, with reality as it is, has been resolved, then there is no need to problematise language anymore. There is no need to problematise first-person experience, pronouns, and so on. There is no need to aspire to perfect expressions that would account for the many different facets of one’s personal experience, simply because experience is not identified with anymore.

This is very different from an idea that is sometimes circulated among contemporary Buddhists, in which one is almost afraid of using first-person statements in relation to one’s own spiritual practise or in relation to other areas of experience.

We hear things such as: “this is just, you know, a manner of speaking, this is just conventional reality, but from the point of view of ultimate reality, one should not be using these conjugations, one should not be using this kind of language because this kind of language does not account for the fact that experience is a process and not a self.” I even met practitioners who would try hard to inflect everything they had to say about themselves in impersonal forms and using verbal forms denoting processes, or who always feel the need to put “I” (say, think, give, receive … whatever) within inverted commas as it is not legitimate to make first-person statements if I am a real practitioner of Buddhist insight.

Oddly enough, the Buddha and all fully awakened beings did not need to problematize this ordinary level of experience. So there is no problem in saying “I am this” and “I am that,” to the extent that I am not taking an unwholesome stance in relation to this experience.

BDG: In light of this insight, what can be said about the postmodern discourse of producing meanings like: self-meaning, other-meaning, internal meaning, external meaning, internal-external meaning? What can we say about the ongoing reengineering and repositioning of one’s experience?

BD: We can say that one’s own identity becomes a stance of identification and of positionality. The mechanics of constant social change, constant reinvention of gender identities, constant reinventions of lineage affiliations, of race, of all possible aspects that define myself in the world as I am, this constant embracing of one or more “intersectional” facets of experience as a crucial aspect, as a crucial sign, as a crucial cause for my own perception of myself and my own positioning in the world to become established – these very mechanics become the essentialised core of self-positionality, of self-conceiving and self-identity as self-identification.

To the point that, unless I am, for example, a member of a certain affinity group or I am for example in the position of sharing a particular gendered sense of identity (or even of more than one: identities) or whatever, I am not able to access the truth, the subjective experiential truth of those who instead share those particular configurations.

Of course, I am simplifying here. And I am totally in favour of respecting and giving voice to discriminated and under-represented experiences, our lived lives (my own included). Yet what tends to happen is that there is a sort of undermining of the very possibility of a common ground, a commonality in the shared sense of arriving at truth.

The “Buddhist agenda,” the early Buddhist agenda of subjectivity, is just that I share with you and others the fact itself of subjective experience. We also share the impact of our subjectivity on our experience, which in turn is a dependently arisen phenomenon. I can then share with others the practice of the Buddhist teachings that help me deconstruct subjectivity – the practice of understanding how I build my own experience in the grip of greed (rāga), hatred (Pali dosa, Sanskrit dveṣa) and delusion (moha), and how I can avoid building it on unwholesome foundations.

With the help of this framing, I can see myself as still possessing greed, hatred and delusion but working towards the heart’s purification, and can regard everyone else from the same point of observation, rather than struggling to assert my own (potentially deluded) standpoint on internal and external reality. Chances are that such a standpoint is fallacious inasmuch as it is conditioned and actually fashioned by the presence of unwholesome conditions in the mind. Therefore, we work towards emancipation from creating, emancipation from biases. We are sharing experience and our practice to understand how we build it.

BDG: So do we approach an experience of reality as it is?

BD: Yes, in Buddhist terms, this is called an “experience of reality in correspondence with reality.” The possibility of arriving at factual knowledge, precisely by understanding how I build biased knowledge. This is very important. The culmination of the Buddha’s awakening is the notion of knowledge and vision in accordance with reality or according to reality, according to the way things have come to be (yathābhūta). This is what Prof. K.N. Jayatilleke, in his seminal book on Buddhist epistemology (Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge, 1963) had already called a “correspondence theory of reality.” This means that the truth or falsity of a statement is measured by the extent to which this statement is aligned with factual reality or contradicts factual reality.

The factual reality in question is the factual reality of my personal, subjective experience. Therefore, it is definitely possible to come to a direct, first-person knowledge and vision of the factual reality of my present experience as it arises in the present without having to elevate it to a form of conceit, māna. Because this is what the unawakened and ignorant mind actually does, namely elevating this conditioned experience of reality, biased experience of reality, to an epistemic absolute. And this is what we ordinarily do in all of our unawakened transactions with the world.

BDG: How does this translate into actual practice?

BD: This is a baseline level of shared humanity, of universal access to truth, which is somehow like a grassroots way of establishing some possibility of viable shared experience based on recognising the status of subjective experience: acknowledging its biases with mindfulness, and working towards “unbiasing.” What is shared is not the contents of experience. And of course, it is not the defences of my own personal identity, social identity, gender identity, and so on. But what is shared is my effort at deconstructing the way all these tokens of identity, as dependently arisen dimensions of selfhood, have been fabricated as my own sense of self.

This is very, very important. To give a practical example: How can I arouse compassion, which must encompass self and other to be authentic, in a way which is not “normative” or wilful, a pious good but often hopeless intention? How can it come directly from a genuine, transformative place?

Say, I cultivate the four establishments of mindfulness (Pali satipaṭṭhāna, Sanskrit smṛtyupasthāna). One of these four is contemplation of the body (kāya in Pali and Sanskrit). This is contemplation of the somatic dimension of subjective experience as it occurs in the present. One exercise of contemplation of the body shared by all known versions of the Discourse on the Establishments of Mindfulness involves mindfulness and investigation directed to the four elements that make up this somatic dimension by way of the elemental qualities of my embodied somatic experience. These are earth, water, fire, and wind.

In early Buddhist thought, these are qualities representing the experience of solidity or inertia (earth), cohesion (water), heat or temperature (fire), and movement (wind). The basic idea is that one examines this very body by way of the elements, recognising: “In this body there are the earth element, the water element, the fire element, and the wind element.” Gradually, one comes to see that form or matter (the somatic aspect) can become an object of experience or cognition only to the extent that they can be perceived. Therefore, there is no subjective experience of bodily form independent of a perception of form. Even the most basic constituent of experience, materiality, can be experienced only in the presence of a conceptual structure, namely perception, perception of bodily form. Somatic perception is a dependently arisen process that involves the presence of the elemental qualities and the activation of a conceptual component in the mind that makes them into aspects of my experience.

Here I understand the conditionality, for example, of the experience of hardness of the earth element of my body. I understand that this is a conditioned phenomenon whereby I have to have a body and a perception of this body for it to be a subjectively relevant experience. The same goes for my perception of the wind element. There has to be a physical counterpart and there has to be a conceptual recognition that perceives this physical or somatic counterpart. So, there is always this dependently arisen aspect of form or matter or embodiment, the somatic aspect of experience, and the perception I have of the arising of this body or this embodiment in the present.

As I practise internally, externally, internally and externally as per the satipatthana contemplative instructions, I come to an understanding that with within and without and within-and-without there is continuity, and there is commonality in this experience of the way I construct my embodiment, my experience of my own embodiment and the way others construct their own experiences of their own embodiment. And this is our meeting point. This is where we can meet. This is where compassion can arise from a fundamental insight into the commonality of the embodied predicament rather than, say, as a noble intention or even a religious ideology. Connection and compassion grounded in insight.

BDG: How does this sit in relation to the postmodern themes we have been discussing?

BD: From an early Buddhist viewpoint, it is clear that the basis for authentic compassion and ethical judgment as well as choice of action is eroded once the possibility of understanding the universal laws of lived experience (as opposed to the “contents”) through wisdom is called into question.

My compassion will ever only be partial if there is no possibility for an insight into the universal reality of human existence that, sure, embraces the individual particulars of experience but is not exclusive or circumscribed to them. And by definition the intention of compassion does not discriminate. According to the early discourses, it is radiated in every direction, encompassing both the person who is radiating it and everyone else.

I can radiate heartfelt compassion impartially without needing to have personally experienced each and every aspect of the experience of other beings afflicted by pain and suffering. I can feel compassion and respond compassionately with the appropriate action, when required. Going by postmodern standpoint theory, this could not work at all, it would be simply impossible. So even the prospect of social justice action or equality/equity work truly informed by a compassionate motivation would fall apart.

Instead, within the early Buddhist framework this is our approach to subjectivity grounded in first-person experience, whereby we can have a shared ground precisely in this investigation of the way experience is constructed. So there definitely is the possibility, and necessity, of including first-person experience, including subjectivity, because what we are trying to understand is how subjectivity comes into being, but there is absolutely no way of wanting to establish the biased aspects, the conditioned aspects and dependently arisen standpoints on the same, based on various kinds of conditions. The myriad psychological, cultural, intellectual, ideological conditionings which form and inform subjective experience are no longer pursued as valid standpoints for episteme, for truth.

BDG: Does this somehow stand in contrast to the postmodern extreme of foregrounding experience in a way which is somehow cutting the bridges between my own self or the self of those who share some affinity with me vis-à-vis the self or the broader selves of others?

BD: Yes, this is my point. I think this is an aspect that can really help put the fascination that we also have sometimes in Buddhist circles for this extreme reengineering of subjectivity into a different kind of perspective.

Consider the epistemic disconnect entire societies are suffering from. Not only are there a million different views and opinions, which of course has always been the case, but there is also a deep erosion of what constitutes legitimate or else illegitimate knowledge. Once, we were entitled to our own opinions but not our facts. Now, we are entitled to our own facts as well. It is no longer a discussion about different opinions or different views, but what is being called into question is factual objective data in the name of the subject’s deep-felt experience of and relationship to such data.

The Buddha reportedly considered it possible to speak from a place of “fact-checking,” as it were. Fact-checking what? Fact-checking the knowable, factual evidence of the presence or else absence of the root defilements of craving and ignorance – or greed, hatred and delusion – in my present experience. I can fact-check the inner place I meet the world from. This elevates the criterion for assessing truth to a much higher level than the merely notional aspect of truth. It is not an emphasis on contents or notions, but one on the mode of knowledge, on personal transformation towards unbiased subjectivity. So here the soteriological orientation is essential.

To conclude, we should think of transformative rather than informative knowledge, or notional, content-oriented knowledge, in the Buddha’s teachings. The transmitted report of the Buddha’s intuition and penetration of his own subjective experience, of him teaching a path of practice that enables others to assess their own subjective experience, is based on his radical transformation of his own defilements of craving and ignorance, which were eradicated with full awakening.

This emphasis on a legitimate ground for truth rooted in personal transformation and oriented towards inner freedom is the opposite of the assumptions of standpoint theories. This is one of the most significant contributions that early Buddhist thought has to offer to wisdom-based education.

As I already said at the outset of our conversation, the knowledge I am talking about is soteriologically-informed, soteriologically-relevant, and soteriologically-oriented throughout.

Ultimately, this legitimate and valid knowledge too is subordinated to the relinquishing of all stances taken on one’s own experiences(s), views, perceptions, cognitions, etc. In fact, in one of the early discourses the Buddha’s chief disciple Sāriputta explains that making an end of dukkha (Pali; Sanskrit duḥkha) does not happen just by means of knowledge (or by means of ethical conduct, or by means of the cooperation of both). Nevertheless, one who lacks knowledge or appropriate ethical conduct will be unable to make an end of dukkha. They are needed to take us to the point in which the breakthrough to awakening can occur. This calls for completely letting go of all that one takes to be I, me, myself and mine. Holding on to them gets in the way of the liberating breakthrough that brings to an end all fascination with experience. So, the final solution, the final move proceeds from wholesome transformative knowledge of the way conditioned experience is constructed to non-clinging to that very knowledge, giving it up without appropriating it any further in a self-referential way.

In the end, it is all about mindfully recognising how much greed, hatred and delusion are still dormant or active in me. This very act of authenticity and truth is transformative here and now, and it lays the foundation for eventually arriving at the complete inner transformation, freedom, and truth with full awakening by untidying our inner and outer world from the construction of ego (another name for identity).