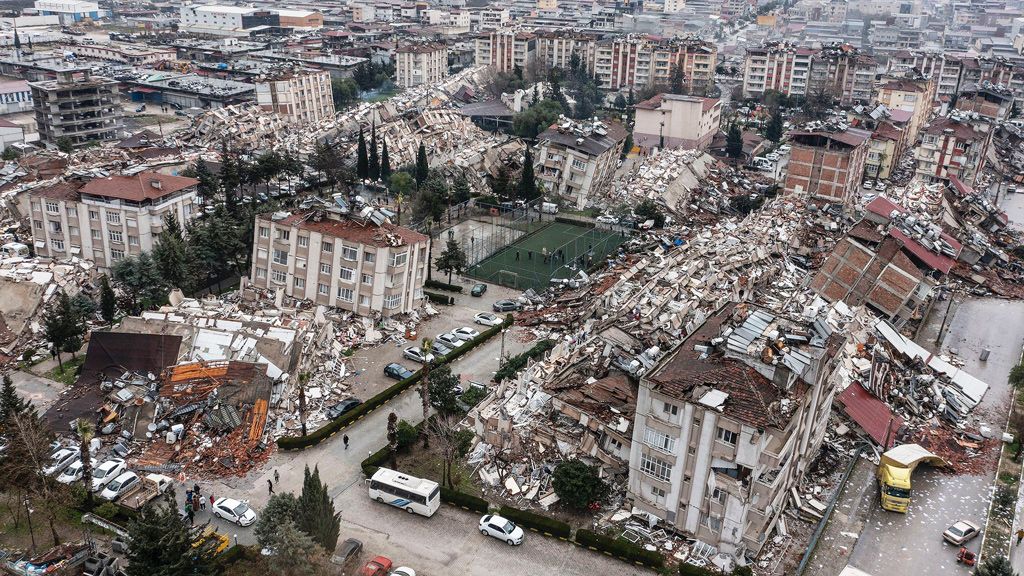

The devastating 7.8 Richter Scale earthquake that occurred in southeastern Turkey, near the Syrian border, has taken over 20,000 lives and injured hundreds of thousands. Hopes for finding more survivors are dimming. It is the deadliest earthquake in the region in contemporary memory. This is a calamity that all of us have been watching closely. For many years, the Turkish community, represented by disciples of Fethullah Gülen, have been active in Hong Kong through their Anatolia Cultural Centre. They proactively organized and participated in interfaith events with non-Islamic groups, including with Buddhists. I can only imagine their horror and pain as they scramble to check on their loved ones in Turkey and collect emergency supplies and funds for the unfolding humanitarian catastrophe.

During natural disasters like these, it is the instinct of well-meaning Buddhists to turn to karma, seeking to explain how such awful and horrific things can happen to people who could never have deserved such agonizing, apparently random deaths. I find the explanation of karma, especially how it can accrue from many earlier lives and ripen in the present, philosophically consistent with the Buddha’s worldview of rebirth and samsara. They are more convincing to me than the various answers to the Problem of Evil (“why does an all-good God allow evil?”). Karma in popular culture also provides an answer to an unanswerable tragedy, while being vague enough to allow the suffering to interpret the causes of their circumstances however they wish.

However, to use karma to comfort ourselves with a one-size-fits-all answer is a mark of carelessness at best, and at worst, callousness. It does a violence to not only the deceased, but to the Buddha’s very position on karma. The Buddha’s philosophical innovation was to ethicize karma, to designate it as volition manifesting as certain types of moral actions that have moral consequences on the source of said volition (our body, speech, and mind). Karma is an intensely individual phenomenon that cannot be extrapolated easily, let alone to thousands or tens of thousands of people. The most we can say about any kind of collective karma is that war begets war, a widespread violence begets a violent society. One could say that the laxity of building standards in Turkey played a part in the vulnerability of the local populace to a powerful earthquake, as news outlets are now reporting. This is a clear, direct causal effect. Yet these are all attributable to human minds. To presume to know what caused the tectonic plates to shift and hit a vulnerable area where the buildings were inadequately prepared is not only presumptuous, but absurd.

Why did this terrible earthquake take away so many innocent lives? In my estimation, it is far preferable to practice a kind of “Noble Silence” than to speculate unhelpfully about the workings of karma. The early Buddhist scriptures originally defined Noble Silence as the response the Buddha gave to questions of metaphysics and cosmology. He simply did not reply to them because they were inconducive to attaining enlightenment. The late Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh advised his students to practice a different kind of Noble Silence, one that returned focus to the present breath. But there is one more kind of Noble Silence, and that is the “compassionate silence” in the face of unspeakable tragedies – what the Judeo-Christian and Islamic theodicists would call “gross evil.” It is not a helpless silence but a humble one. It admits to not having speculative answers, and that answers are not as important as help and understanding.

This kind of silence leaves generous, open space for tears and weeping. There is no temptation to override the sorrow or fill the heartbroken silence with hasty explanations that reassure the discomfited bystander. This silence allows the grief to be foregrounded, to let the discomfort and anger and grief be, without being suffocated or stifled. We who are fortunate enough to be onlookers must be mindful to not prioritize ourselves over those who are directly suffering.

“Why do bad things happen to good people?” Before the existence of God, before consciousness, perhaps even before death and the hereafter, I feel that this single question might have been the existential question. I can imagine that it was shouted up at the sky, millions of years ago, by an angry ancestor who, after suffering an unstoppable natural disaster like a drought, famine, or indeed, earthquake, felt stirring in them a primal sense of injustice and powerlessness. This question is perhaps the ultimate, unanswerable mystery of the human condition, one that is perhaps best met with compassionate silence.

Related news from BDG

See more

Turkey earthquake: Why did so many buildings collapse? (BBC News)