Ancient and medieval Pakistan was a millennia-old crossroads of culture and religion that holds deep secrets and unsolved mysteries. The site of Kafir Kot, where a collection of exquisitely detailed religious towers stands, is one of these places. It is in Dera Ismail Khan District, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, near the cities of Mianwali and Kundian in Punjab (32°30’0N 71°19’60E). Kafir Kot is one of the testing grounds for a procedure of digital reconstruction spearheaded by the Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Directorate of Archaeology and Museums (KPDOAM).

The dating of Kafir Kot identifies the foundations as rather ancient, going back to the Buddhist-influenced Kushan Empire at the turn of the Common Era. The structures that stand today, however, were built during the reign of the Hindu Shahis, an enigmatic dynasty that ruled over the Kabul Valley, western Punjab, and the Gandhara region for a brief few centuries from 822–1026. They left no writing and very few inscriptions. They irrupt into history with only a few clues from scattered chronicles, mentions in coins, and a few stone inscriptions.

Local legend has it that there were two brothers, Til and Bil, who ruled over the land as the last Hindu Shahi kings. They built these temples, with the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa complex now called “Northern Kafir Kot” as opposed to the “Southern Kafir Kot” 85 kilometers away in modern-day Bilot Sharif. I have searched the Internet for information about the actual objects of religious worship, but this key piece of the puzzle remains a mystery.

With Kafir Kot as a case study, KPDOAM is applying it to different sites across Pakistan, including the Buddhist monasteries and ruins like Takht-i-Bahi, the Bhamala complex, the Amluk-Dara stupa, and more. So important is the site to KPDOAM that the Digital Heritage Center has adopted the Kafir Kot temple as part of its logo.

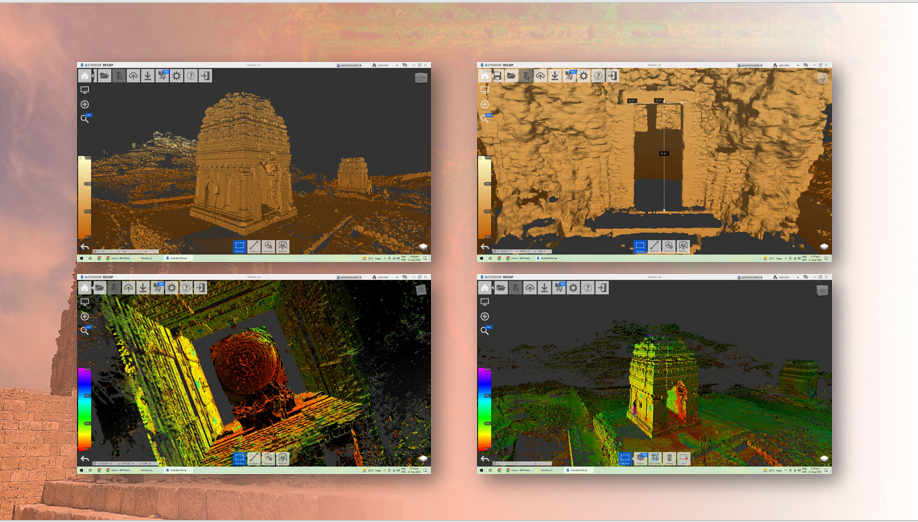

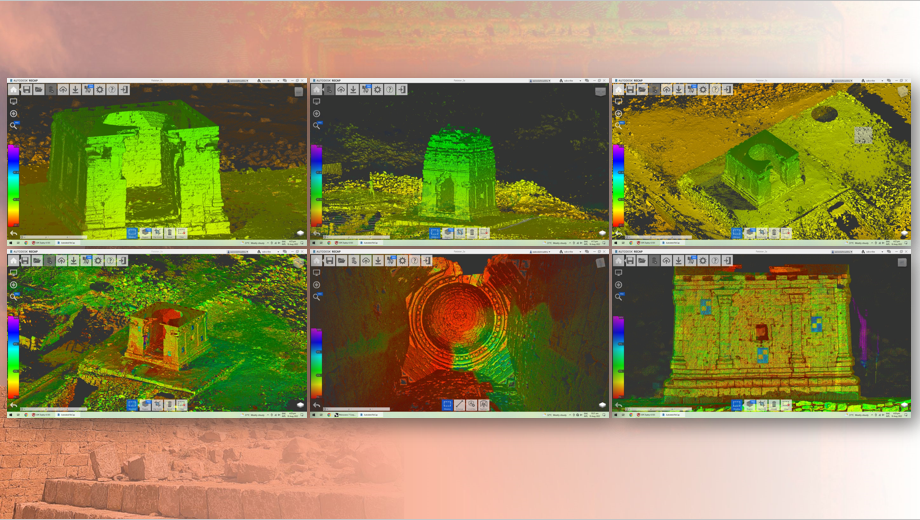

Scanning to BIM: The first stage deploys the FARO Terrestrial Laser Scanner to map out the site. The laser scanner, along with digital cameras, are deployed on-site. These instruments process each individual structure and their surroundings, with the information sent to the computer for the “H-BIM” stage.

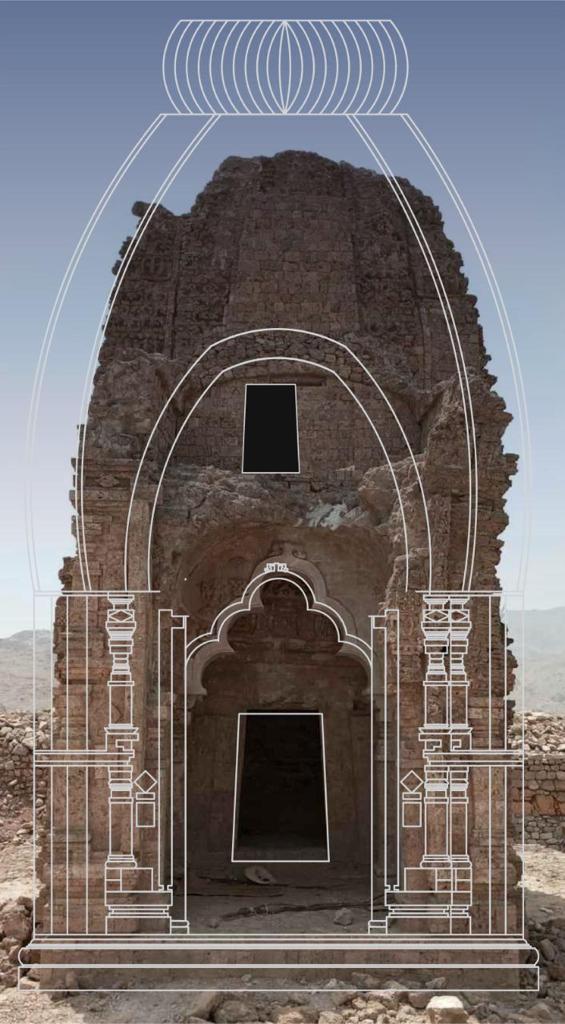

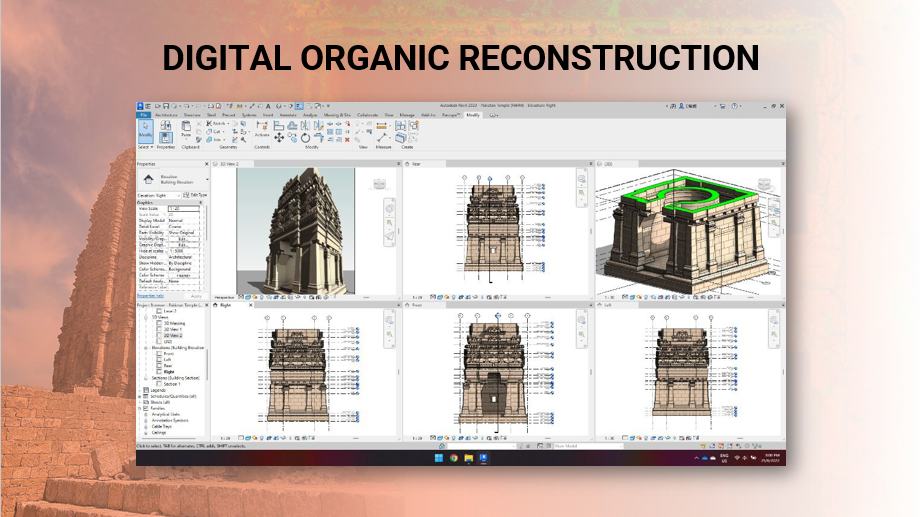

H-BIM: Heritage Building Information Modeling is the process through which researchers use a range of software programs to combine the image and scan data, before producing accurate renders of the site’s dimensions. Frameworks are created by meshing, texturing, and mapping the BIM objects onto a 3D surface model. The mapping constitutes the last part of H-BIM, with full models indicating details behind the objects’ surfaces, its material composition, and its methods of construction.

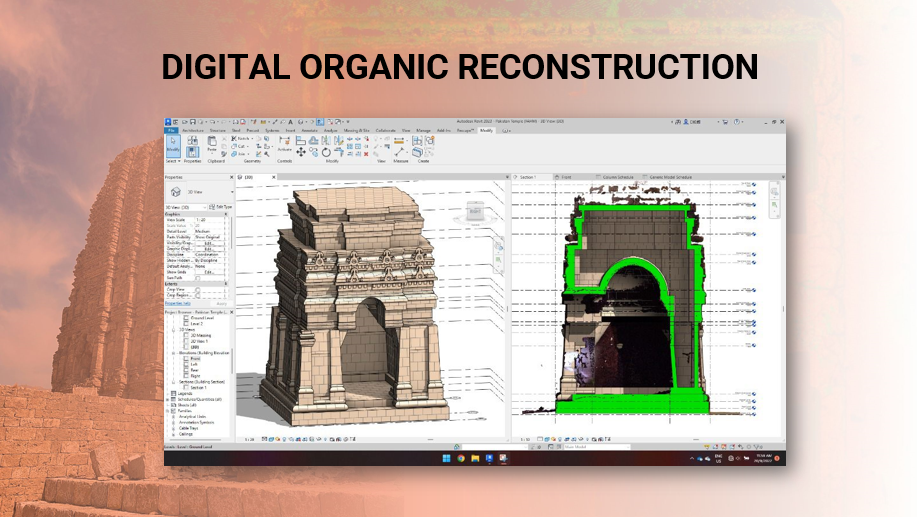

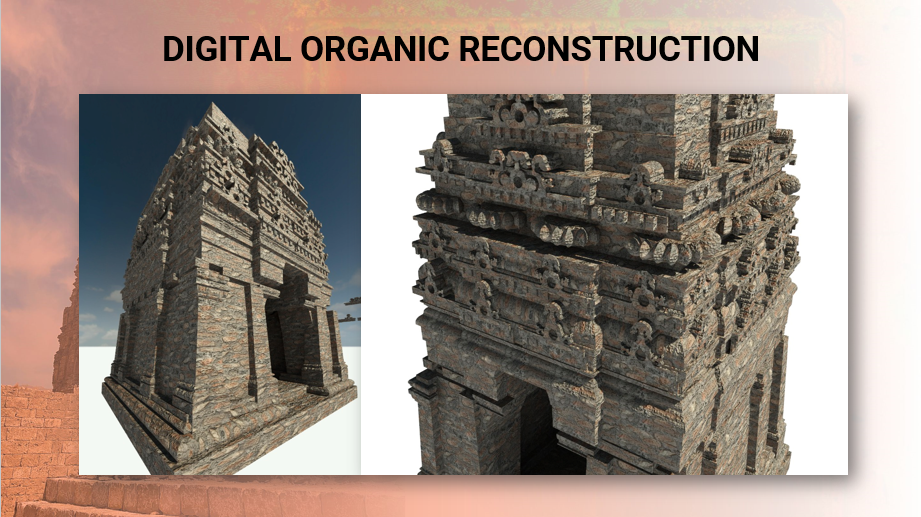

Organic reconstruction process: Coined by the KPDOAM team independently, organic reconstruction denotes the addition of missing information to the H-BIM. These include missing parts of the structure that were lost due to time, the climate, or human intervention. To avoid error as much as possible, the team rigorously collects data on the design philosophy, archaeology, architecture, and materials of the historical period. Only then are additions made to the 3D surface model.

KPDOAM’s team shared with me how this plan aims to create the most accurate digital renders of the temples, allowing a diverse range of high-tech applications. These digital reconstructions – their dimensions, layouts, materials, every detail – will be made available for researchers around the world. These original renderings can be made into life-size replicas that allow tourists to see how the original site would have looked, without putting human pressure on the extant ruins. This is the “Dunhuang treatment,” which empowers government bodies to protect the original sites (by closing them except to researchers) while tourists can be directed to a tourist center with augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) facilities. KPDOAM already plans to showcase these reconstructions as a life-size display for a special exhibit about Kafir Kot at Kuala Lumpur’s National Museum.

This article was written in collaboration with the Digital Heritage Center of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPDOAM)