Though it was burned to the ground in 1860 and looted at different points during China’s tumultuous 20th Century, the Old Summer Palace, or the Yuanmingyuan, has taken on a life beyond its ignominious end. In a perverse sense, its story is still to be written precisely because so much was looted from it, that repatriating its artifacts is an ongoing work. Its most famous plunder are the “bronze heads” of the Haiyantang fountain. These heads of the Chinese Zodiac’s twelve animals were looted by Anglo-French forces at the frenzied climax of the Second Opium War, before being scattered across the world. Five remain missing, far away from home, and possibly irretrievable.

“The grand gathering of the century” does not sound so melodramatic for an exhibit showcasing four of the seven repatriated Zodiac Heads. These are the original versions of the ox, pig, tiger, and monkey heads, on display at the Indra and Harry Banga Gallery at City University in Hong Kong from 4 July to 31 August. This is Phase One. Phase Two will feature all twelve heads in replica form from 5 September to 31 October. Apart from the bronze heads, the exhibit features paintings, clocks, and other items demonstrating the cross-cultural tastes of the Qing emperors. There are also Zhou-era artifacts (the Qing monarchs idolized the Zhou Dynasty) and digital interactive stations.

Amidst a flurry of press meetings and guided tours, Dr. Libby Chan, director of the Gallery, gave a press tour on the 6th, taking us through the exhibit and exhaustively sharing her expertise and knowledge about the items on display. She said that she was struck by the cross-cultural interactions in the art and artifacts: “We hope that visitors to the exhibit, and viewers of the interactive multimedia and the artifacts, will understand better the nature of the Yuanmingyuan’s East-West cultural exchanges. The art technology that we have deployed will hopefully stimulate broader community engagement. The larger goal is to help people learn and be inspired to preserve the Yuanmingyuan.”

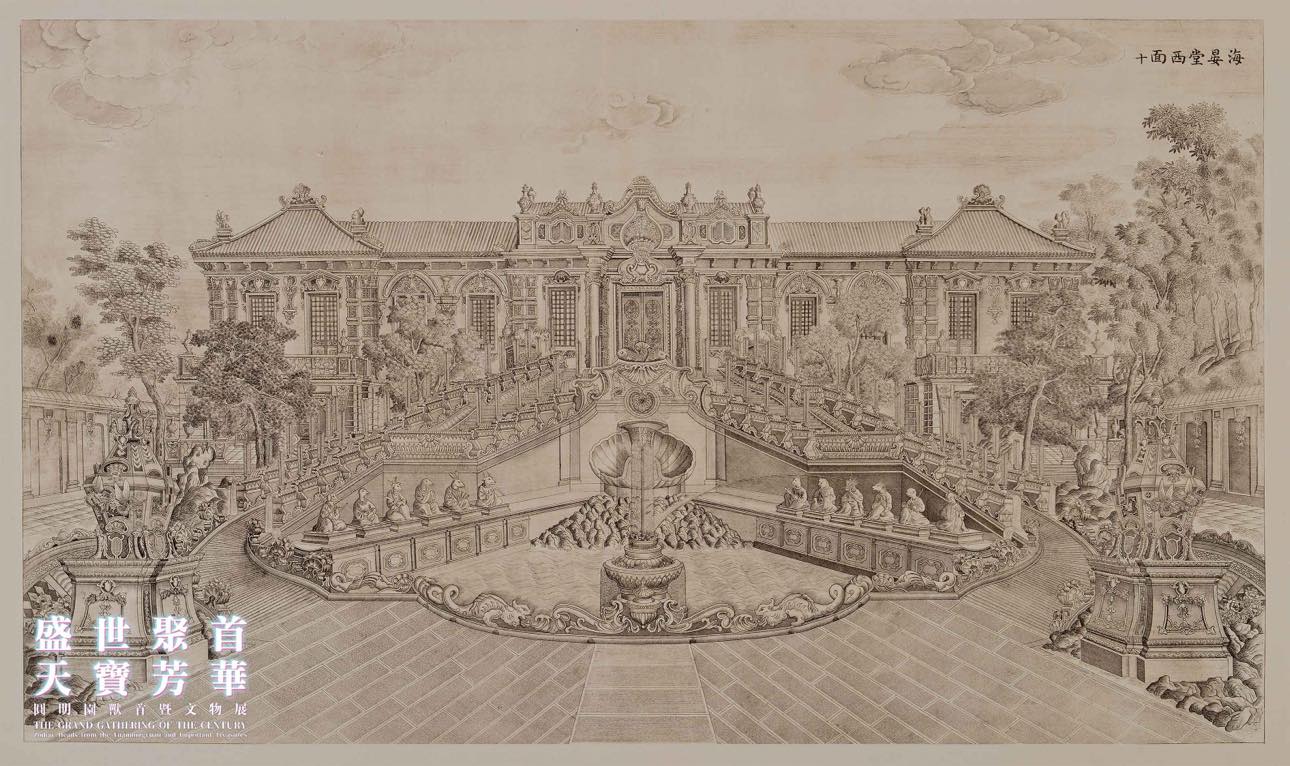

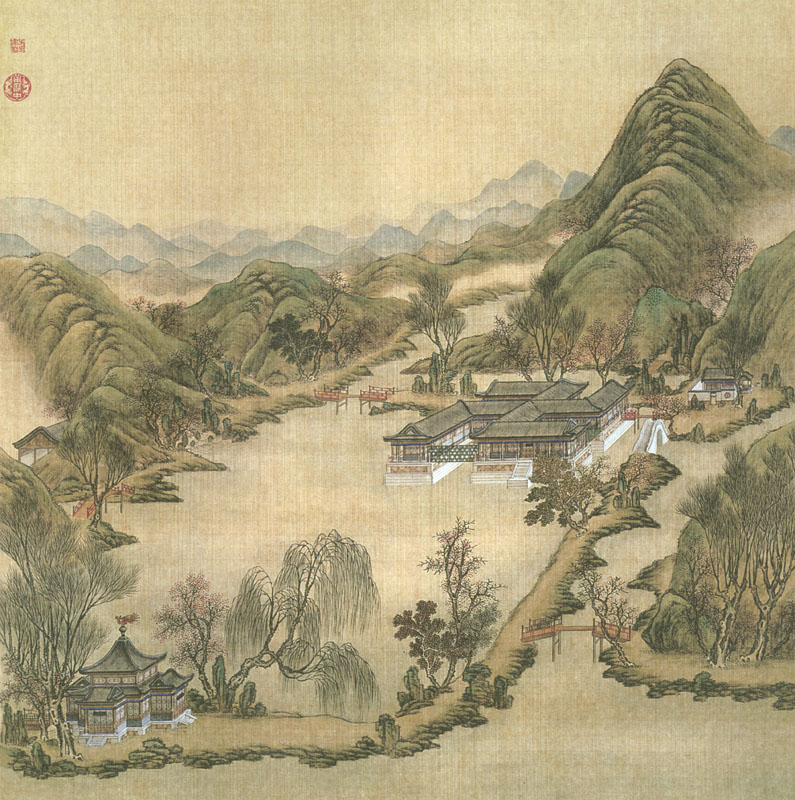

The Haiyantang fountain was part of the iconic “Western mansions” (xiyang lou) designed by great men like Giuseppe Castiglione, Michel Benoist, Bonaventura Moggi, and Ignatius Sichelbart under the employ of the Qianlong Emperor (1711–99). This Western-inspired complex, in turn, was about 7 hectares, composing only a tiny portion of the 860-hectares Yuanmingyuan, making it larger than both the Forbidden City and the Vatican. The immensity of this mega-residence – with entire islands connected mostly by lavish waterways, grand lakes, and stunning artificial seas – was made possible by expansion projects under successive monarchs.

While the Qianlong Emperor did most of the expanding, his father, the Yongzheng Emperor (1678–1735), was the one to initiate this informal custom upon his accession. He also established the Yuanmingyuan as the imperial family’s primary residence. Until its razing, the Qing royals spent more time there than in the Forbidden City.

The Yongzheng Emperor’s Buddhist connections are well-known: he established a Buddhist publishing house and wrote the Yu xuan yu lu (御选语录) in 1732, a 19-volume anthology of his favorite Buddhist compositions in Chinese. As a universal monarch ruling over diverse ethnic groups, cultures, and religions, he was said to have favored Chan Buddhism, but more overtly supported the Buddhism of Tibet. His donation of the Yonghegong Temple in downtown Beijing to the Gelug school was his most famous act of piety, especially since his son the Qianlong Emperor was born there. (Columbia Tibetan Studies)

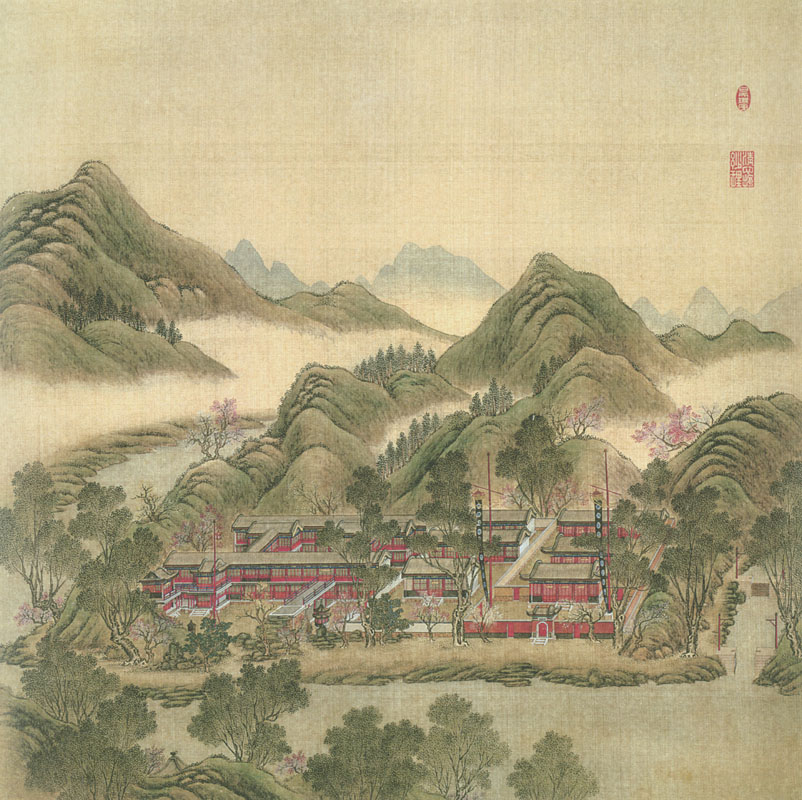

Vajrayana Buddhism is intensely esoteric, and the Aisin Gioro family was partial to Tibetan Buddhism long before the Yongzheng Emperor. Buddhist imagery was therefore encoded into the Old Summer Palace, with at least two explicitly Buddhist-themed islands in the 1744 text, Forty Scenes of the Yuanmingyuan. These are “Peace and Harmony Everywhere (Swastika House)” and “Dazzling Eaves Under Heaven (Buddhist compound).” Other islands had eclectic spiritual themes with Buddhist landmarks, like “Merciful Clouds Protect All (Island of Shrines).” I suspect another, “Vast Empty Clear Mirror,” represented the Chan aspect of Yongzheng’s Buddhist practice.

Since these sites were all based in the largest “Yuanmingyuan” area, distinct from the “Changchunyuan” area where the Western mansions were located, we only know these sites’ locations, with their physical structures long lost.

So what is the Yuanmingyuan? I leave the last word to artist-mystic Rebecca Wong: “We often think of its destruction as a stain on China’s national honor,” she said. A long-time devotee of the Yuanmingyuan’s artistic tradition, she had accompanied me to the press event and has painted several of the Forty Scenes of the Yuanmingyuan, including the Island of Shrines. “I would go further than that. It was like destroying the Vatican of the Qing Dynasty. It was not only the political center of the emperor, but it was also the esoteric Buddhist heart of China, since it was designed as a Pure Land with a temple of 33 rooms at its heart. As far as I am concerned, when it was burnt down, the Qing Dynasty was doomed to end even though it endured until 1911.”

The Yuanmingyuan’s name means “garden of perfect brightness.” It represents enlightenment, imperial glory, and ironically, presence amidst absence. The modern-day grounds are almost completely scoured of any trace of its bygone beauty and exquisiteness. This dark nothingness only means that its perfect brightness is seared into the consciousness of the Chinese more vividly than ever.

See more

Four original zodiac heads from the Yuanmingyuan featured in a new exhibition at CityU (City University)

The Yongzheng Emperor (Columbia Tibetan Studies)

Related features from BDG

Related blog posts from BDG

Rebecca Wong’s Dreamscapes of Art, Archetypes, and Ascension