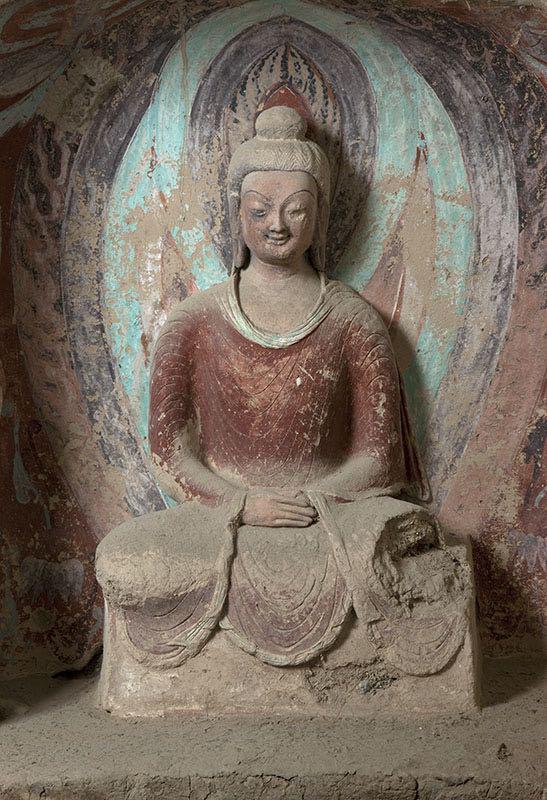

Among the many masterpieces of the Mogao Grottoes at Dunhuang, one in particular stands out. It is the “Mona Lisa of the East” Buddha sculpture in Cave 259, one of the exemplar examples of early Mogao art. It is one of the favorite pieces of Zhang Xiaogang, deputy head of the Dunhuang Academy and director of its Archaeology Institute. Zhang is one of the core figures working at Mogao today. In April, I visited the Dunhuang Academy to listen to a comprehensive talk by Zhang about the history and characteristics of the sites under the Academy’s stewardship.

In February, the Dunhuang Academy announced that the second volume of the Complete Collection of the Dunhuang Grottoes (《敦煌石窟全集》第二卷) was published. This was an archaeological report of Caves 256, 257 and 259 at the Mogao Grottoes, which took more than 10 years to compile. In addition to the comprehensive text itself, the second volume contains nearly 300 illustrations, close to 100 archaeological surveying plates, more than 900 photographs, and 43 digital panoramas.

The first volume had been published in 2011 under the editorship of Dr. Fan Jinshi. This year’s publication of the second volume marks the 30th anniversary of this ongoing project, since Dr. Fan launched it in 1994 back when she was vice president (and the Academy was still then known as the Dunhuang Research Institute).

“This was first formal cave temple archaeological report in China,” noted Zhang, a similar observation he had shared with Xinhua in February. “Archaeological reports offer both the most comprehensive data of caves and the most scientifically-minded archival methods. The archaeological reports represent the aspiration that even if the caves no longer exist in the future, successive generations can still fully restore the caves based on these reports.”

This is a monumental ambition. It is not lost on Dunhuangologists around the world that the Dunhuang Academy is preoccupied with the eventual wearing out of the caves due to their immense popularity, nature, and time. They enjoy a unique place in Chinese heritage tourism and Buddhist pilgrimage. As if echoing the Buddhist lesson of impermanence, specialists at the Academy base their research, tourism methodology, and conservation philosophy (in effect, all their careers) on the predication that the sculptures and murals are in terminal deterioration. The digital center of the Academy, along with its other projects, have this prime concern on their leaders’ minds.

Now, with Dr. Fan having retired, it is Zhang who has succeeded her in a position that echoes her vision, which foresaw the caves’ needs in the 21st century. Those needs will remain constant, or evolve, according to the conditions of the next few years and decades.

Yet: why Mona Lisa of the East? It would seem fitting that Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa actually be called the “Guan Yin of the West,” since the 5th century Buddha of Cave 259 came first. The history of Dunhuang is the history of the world, a crossroads that, since the 19th century, has literally expanded across the globe through artifacts, scholarship, and texts. We can still speak of the Mogao Caves in physical terms, but their art and Buddhist message have long become set on the horizon of eternity.