Xumi Fushou Temple is one of the Eight Outer Temples that brought Vajrayana Buddhist blessings to the Chengde Mountain Resort (bishu shanzhuang), the vast complex of gardens, hunting grounds, and palaces that constituted both the leisurely retreat of several generations of Qing-era emperors from Kangxi onwards, as well as a political center for managing Mongolian and Tibetan suzerains.

Xumi Fushou Temple was built in 1780, the 45th year of the Qianlong Emperor’s reign, as part of the celebrations for his 70th birthday. More importantly, it would house the 6th Panchen Lama, Lobsang Palden Yeshe (1738–80), and his entourage from Tibet, who would join the emperor’s birthday festivities. I visited this temple during a brief stay in Chengde, and the grounds are truly charged with spiritual significance. The center of this power is at the Lofty and Solemn Hall (miaogao zhuang yan妙高庄严), which was constructed for the Panchen Lama to give teachings and to function as a meditation and ritual space.

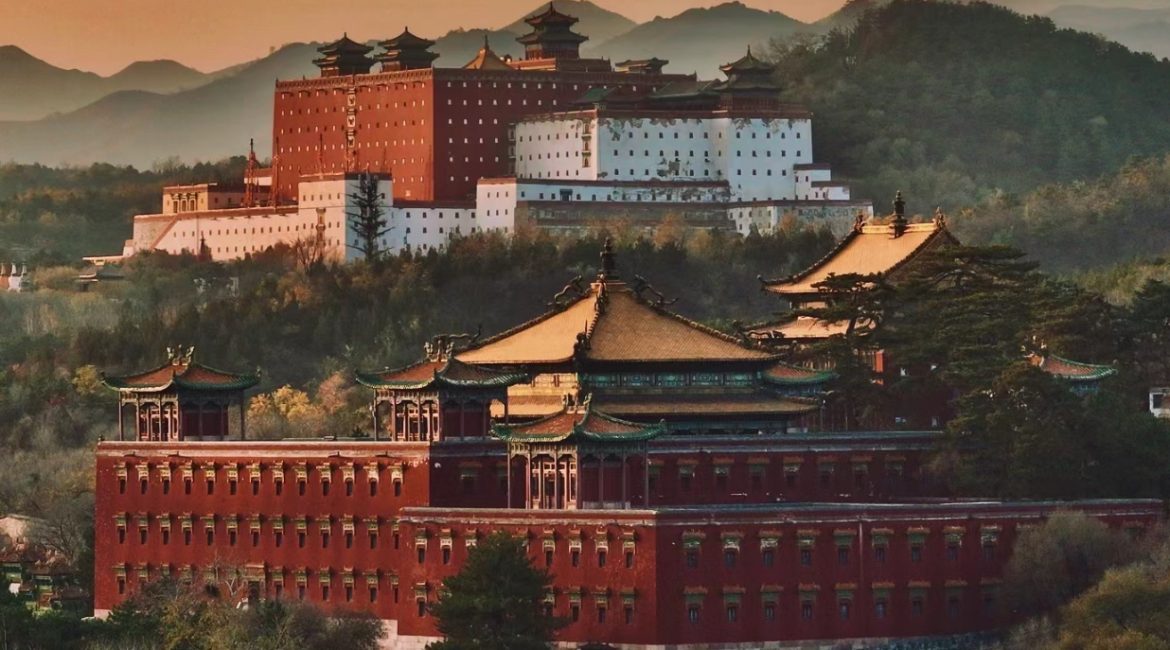

Roughly translated in English as Blessings and Longevity of Sumeru Temple, Xumi Fushou Temple is designated a AAAAA site by the Chinese government, but despite its beauty it is not immediately apparent why. It is far from the oldest temple in northern China, and its inventory (taken in 1800) does not reveal any artifact of major sacrality. Furthermore, it is one of the several “replica” temples in the Mountain Resort. It is an aesthetically hybrid temple, with the Tibetan exterior of a gompa, yet with a Chinese-style layout. Like its neighboring Putuo Zongcheng Temple, built to imitate the Potala Palace of the Dalai Lamas in Lhasa, Xumi Fushou Temple was modelled after Tashilhunpo Monastery in Shigatse. In this sense, the architectural vision behind the temple is not particularly special. Yet the instinct for replication, perhaps reaching its apogee in the Qianlong Emperor’s time, had a very specific reason:

The practice of constructing Buddhist sites honoring political victories harked back to the Kangxi emperor (r. 1662–1723) who built the Huizong Monastery in Dolonnor for the Khalka Mongols after their surrender to the Manchus in 1691. The Qianlong emperor adopted this practice and built two more temples commemorating the conclusion of political victories: the Puning Temple (普宁寺), which was modeled after Bsam yas Monastery, in 1755 at Chengde to honor the Manchu defeat of the Dzungar Mongols, and the Putuozongchengmiao (普陀宗乘庙), modeled after the Potala Palace in Lhasa, in 1771 at Chengde for the combined occasions of the Empress Dowager’s eightieth birthday, Qianlong’s sixtieth birthday, and the return of the Kalmuk (or Torghut) Mongols to the Qing empire. . . .

In 1778, the Qianlong emperor was overjoyed at the news that the Sixth Panchen Lama wished to be present at his birthday celebrations (likely influenced by Rol pa’i rdo rje, the senior-most lama in the imperial court and guru to Qianlong), as he was then the highest ranking prelate in Tibet and his visit would mark the second most important state visit from Tibet since the visit of the Fifth Dalai Lama.

(Columbia Tibetan Studies)

The Qing’s ruling house of Aisin Gioro understood itself through the lens of “multiple emperorships,” with the charge of ruling over a multi-ethnic empire spanning Manchus, Tibetans, Mongolians, and Han Chinese. Therefore, the steles commemorating the founding of politically important temples were always multilingual, in the four languages of the empire.

In the case of Xumi Fushou Temple’s stele, the emperor is open about his intention: in Chinese, Manchu, Tibetan, and Mongolian, Qianlong proclaims, under the Qing, the two greatest reincarnations of the Gelugpa founder Tsongkhapa, the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama, occupied “separate monastic seats located at great distances from each other.” Yet thanks to the auspices of the imperial birthdays, “these two seats of Vajrayana Buddhism were brought together side by side, in replication, at Chengde.” (Columbia Tibetan Studies) All the temples at Chengde were political in nature, and united China and its frontiers into one great, single family.

Seen in this light, the slightly unwieldy name of “Blessings and Longevity of Sumeru Temple” seems all the special for its inclusion of the Buddhist cosmological term “Sumeru,” indicating the cosmic significance of the complex.

The meeting between the Qianlong Emperor and the Panchen Lama is celebrated in Chengde (there is a wax model reconstruction of the encounter inside the Chengde Museum) as one of the most significant events for the Qing dynasty and the imperial management of Tibet and Mongolia. We return to why Xumi Fushou Temple was assigned China’s top heritage and tourism rating, one that is higher than several sites along the Hexi Corridor and the Silk Road. The 6th Panchen Lama died of smallpox in the same year as his visit, and his passing was mourned with full honors by the Qing. But the statement had been made. The bell cannot be unrung. Only under the Qing imperium, and by extension the modern Chinese state that succeeded it, can the Panchen and Dalai Lamas be united, and thus Tibet be one.

See more

Xumifushou Temple (Columbia Tibetan Studies)