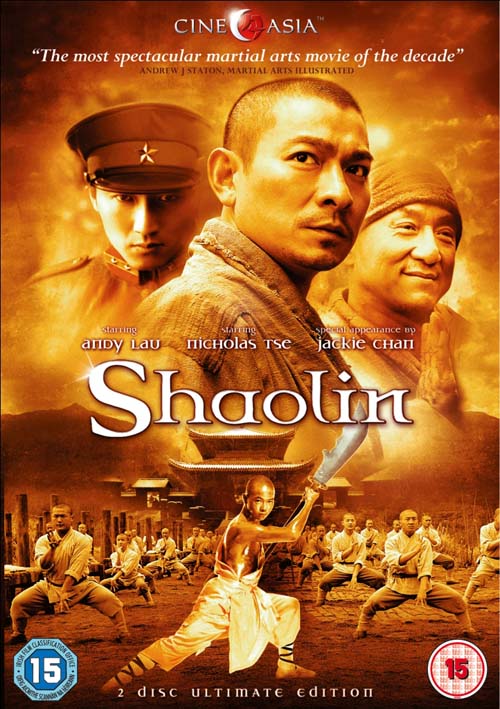

I have mixed feelings about films that have an overtly religious element, especially when the religion plays a central role in a movie focused on bone-crunching action, head-crushing martial arts, and temple explosions. I class Shaolin, which is an overwhelmingly positive portrayal of the martial art masters in Republican-era China, as one such guilty indulgence. This is not to say I didn’t enjoy the film. The action and martial arts film lover in me was very happy with it, and I like how the Shaolin monks are depicted faithfully as defenders of the dispossessed and redeemers of superstar Andy Lau’s character, a warlord-turned-monk who forgives the lieutenant that betrayed him (played by Nicholas Tse).

At the heart of the film is not just the redemption of Andy Lau’s character, but the insight that violence and cruelty are cyclical: it takes a big, brave man to break the cycle of revenge by choosing forgiveness, letting go of hate, and transforming enemies in the process. Wu Jing, who is currently China’s most sought-after male star thanks to his role in the wildly popular Wolf Warriors 2, also makes a welcome appearance as one of the more experienced monks. His character dies defending the temple, along Yu Xing’s character (Yu Xing himself is a 32nd generation Shaolin monk).

The story itself isn’t complicated, portraying a Republican China mired in chaos and disunity while apolitical monks defend their temple from militaristic forces. But is this a harmlessly violent blockbuster where monks deploy their antique weapons and preternatural martial arts against troops wielding contemporary bayonets and rifles, and cheer and groan at all the destruction and bloodshed? Or are we supposed to emotionally engage with Andy Lau’s character, who is at first a domineering warlord but later becomes a selfless protector of the innocent and whose death tugs at our heartstrings? As it turns out, both.

I watched the film at least a couple of times a few years ago. What am I supposed to feel at cinematic representations of monks being attacked and killed by soldiers? It gets even more confusing when it comes to monks defending against and killing soldiers. Should the audience cheer? Should we recoil? Should we do both? I have a video game where the good guys have super moves contradictorily named, “heroic brutalities.” We laughed endlessly at how silly that moniker was. Yet the prolific action scenes in Shaolin raise the question: is it possible to be heroically brutal? Brutally heroic? It makes me uncomfortable just thinking about it.

The scene that really tries to tie the action with the spiritual or moral message is when Lau’s character, mortally wounded after the climatic fight with his lieutenant, falls into the hands of the Shaolin temple’s large Buddha statue and expires, serene and without regrets. Perhaps this is the part that redeems the film and the guilty pleasure of its viewers. It might be a movie that has violence as its selling point and perhaps could be criticized for that. But its message is distinct and fairly spot-on: that even men and women who have been mired in war and inhumanity their whole lives deserve to find peace.