In this series about the busshi – artisans and craftsmen of wooden sculptures for Buddhist temples and patrons – a common thread has been the constancy and conservatism of Japanese crafting techniques. Many, which we covered in a previous entry, were consolidated into an informal “canon” over just a couple of centuries, between Jōchō’s (d. 1057) aristocrat-dominated era and the establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate. Even then, the shifts during the Kamakura period were more about taste and aesthetic preference than specifically new ways of making Buddhist art. In Yujiro Seki’s Carving the Divine documentary, the transmission by experienced seniors to their kohai resembles the mood of martial art dojos – the techniques are openly available for all to learn, but perfecting them requires tireless dedication and good teachers.

David Bilbrey of the Butsuzōtion blog, which expands on the historical content of Carving the Divine, asserts that most art historians see the centuries of 1186–1333 as having “bookended the pinnacle of ancient Japanese sculpting.” He further notes, “Though the materials, surface details and popularity of various Buddhist characters may have shifted and evolved over time, little has changed in terms of how master Buddhist sculptors have passed on the knowledge of creating spiritual imagery to their apprentices in order to produce statuary for temples and patrons.” (Butsuzōtion)

So significant was Jōchō that we could perhaps, similar to how the birth of Jesus is used in the Gregorian calendar, use “before” and “after” Jōchō to evaluate how Buddhist sculpture evolved from an important art. The artisans before Jōchō are widely seen to have been absorbing and learning from various artistic influences, from China’s Northern Wei dynasty (386–535) to the Korean style a-la the “pensive bodhisattva” (Maitreya; Miroku) at Kōryū-ji, which is these days a Shingon temple in Kyoto.

In China itself, artists would take inspiration from non-Sinitic forces like the Northern Wei’s ethnically Tuoba Xianbei people, while the Koreans proved to the Japanese that Chinese precedents could be re-interpreted into something more befitting local tastes. Artists would travel to China or Korea, or teachers would sail over to Japan to teach. Buddhist sculpture across East Asia was therefore a uniquely porous and “open” cultural and artistic phenomenon.

If there is one figure who is second only to Jōchō in importance, it would be the 7th century Tori-busshi, or Kuratsukuri Tori. Jōchō represented Japanese creative identity and self-distinction from the other great East Asian civilizations of the Chinese heartland or the Korean peninsula. While Tori-busshi was also a localizer, he could be said to have represented everything noble and vibrant about Sino-Japanese exchange and a broader understanding of East Asian bonds.

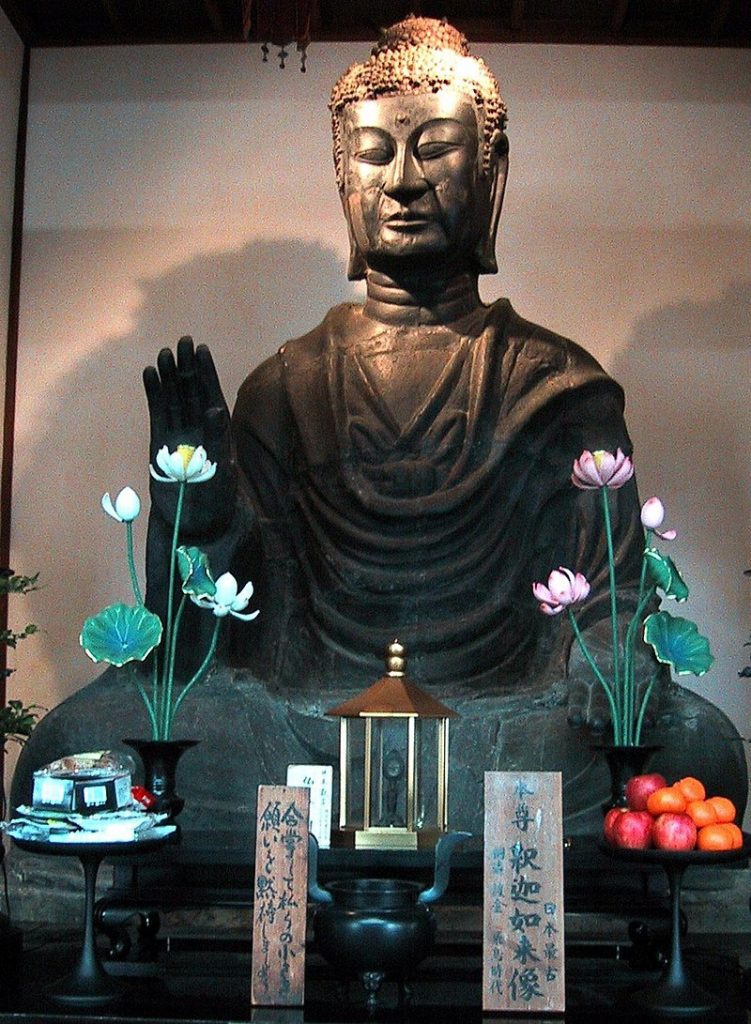

Tori-busshi is said to have been the grandson of a Chinese immigrant, a humble saddle maker that moved to Japan and passed on his craft down the generations to Tori-busshi. Bilbrey notes that he worked with diverse materials, from wood to lacquer to bronze. He would not stay in his saddle maker station for long, carving the Asuka Daibutsu image at Asuka-dera in Nara. Its completion year was 606 and it is his earliest extant work.

He then caught the attention of Prince Shōtoku (574–622), who came to embrace Tori-busshi as his favorite sculptor. His court would regularly commission him, and other prestigious patrons around Nara followed Prince Shōtoku’s lead in commissioning Tori-busshi. The once-humble saddle maker generally favored flat surfaces and compositions optimized for frontal viewing. At first, they betrayed Northern Wei influences, but Tori-busshi quickly refined them by developing a gentle, serene, and tranquil mood, refining a peaceful quality which was likely drawn from exposure to Korean styles. His merging of Northern Wei with Korean aesthetics came to be known as Tori Yoshiki – Tori style.

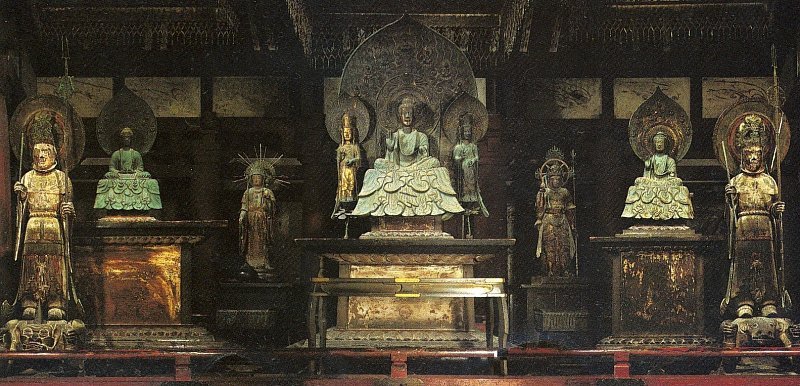

In some ways, it was Tori style – not Jōchō’s jōchōyo – that was the first milestone of a localized Japanese butsuzo personality, unabashedly embracing foreign influences. Bilbrey writes: “In 623, his Shaka Triad was completed, which is still located in its original place of veneration at the Hōryū-ji. Cast in bronze, this group is considered to be Tori’s masterpiece. His signature can be read on the back side of the halo, and the central figure in lotus position is flanked with a bodhisattva on each side. The flat surfaces suggesting the pedestal are enriched by an unrealistic, yet highly idealized treatment of the flowing robes.” (Butsuzōtion)

Despite Shōtoku’s semi-legendary persona, it is likely that the man behind the myth most likely projected to court historians a cosmopolitan attitude (an interest in Chinese art and culture was a signifier of fine taste), which went hand-in-hand with his piety. In Japanese Buddhist historiography, he saw himself as a servant of the Three Treasures, and personally drove much of the Buddhist diffusion in the imperial court and throughout Japan. The Buddhist community was able to secure a permanent foothold in the country thanks to the Prince’s generous and passionate patronage.

This personage in the hallowed hall of Japanese national identity and statehood died one year before he could enjoy his favorite sculptor’s Shaka Triad. But their relationship – and the story of Tori-busshi – perhaps bear models of peace and religious-artistic creativity that contemporary relations could be invigorated by.

Carving the Divine is now crowdfunding for distribution on IndieGoGo

See more

A Legacy Takes Flight (Butsuzōtion)

Related blog posts from BDG

Techniques of the Masters: How to Carve Japanese Buddhist Statuary

Lives of the Busshi: Japanese Sculpture Under the Kamakura

Of Artisans and Aristos: Butsuzo Flourishing in Japan

Jocho: The maestro that started Japanese Buddhist Sculpture

The Yuji Experience: A Singular Voice for Japanese Buddhist Sculpture