The tradition of busshi, which Yujiro Seki showcases in his documentary Carving the Divine, is a complex nexus of overlapping but also divergent woodcarving traditions that have shared one goal for a thousand years. Writing on the Butsuzōtion blog, David Bilbrey says that a distinct Japanese style of butsuzo (Buddhist woodcarving) emerged thanks to the contributions of one man: Jocho (d. 1057). There was Buddhist sculpture and woodworking principles in the country before Jocho, of course. Monasteries, royals, and aristocrats in the Asuka, Nara and early Heian periods drew their artistic inspiration from primarily Tang (618–907) aesthetics and styles from Unified Silla (668–935). However, Jocho’s story is surely a case of “great men of history,” except for the history of art.

“Jōchō was a Kyoto-based busshi whose sculpting prowess was well established by 1020. Hailing from a long line of Busshi, he was an active sculptor favored by nobility and temples, and we have many temple records of the important works he sculpted, but we unfortunately only have one extant sculptural grouping from his life. Thankfully, though, the work that does exist is widely considered to be his greatest work, and it is of unsurmountable importance from late in the artist’s career, bearing his perfected style which still influences Japanese Buddhist sculptors to this day.”

Butsuzōtion

Jocho pioneered a truly “local” or “Japanified” style of butsuzo, which art historians, busshi, and Japanese Buddhist leaders largely agree to embody several qualities (among many others):

– Simplicity and gentleness in presentation, posture, and poise;

– Physically, the Buddha’s face is rounder and more balanced;

– The statue’s width in relation to height are more carefully calculated;

– The appearance of the robes, along with its drapes and folds, are naturalistic and cover healthy, broad physical contours.

This style of butsuzo came to be called wayo, and not only that, but he pioneered his own personal style as well: jōchōyo, “Jōchō style.” (Butsuzōtion) As if that were not enough, his art’s lineage grew to form three distinct, important schools of sculpture: the Inpa and Enpa studios based in Kyoto, and the Keiha school in Nara. He was quite literally the “patriarch” of Japanese Buddhist woodcarving.

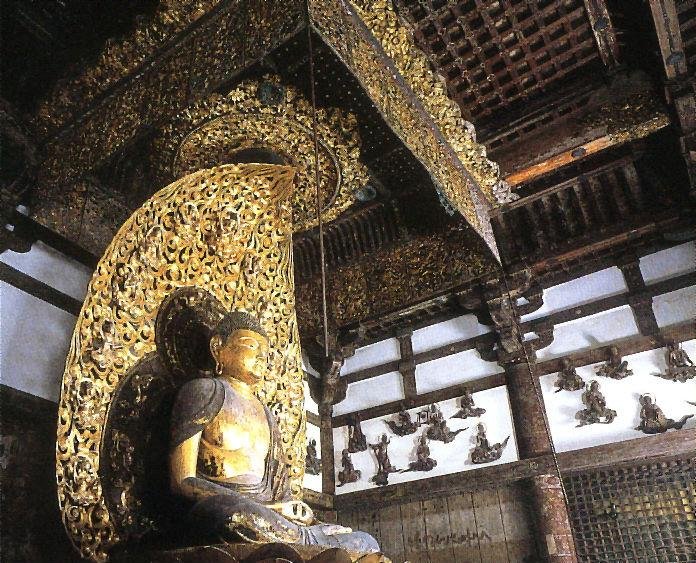

One of the best examples of the master’s craftsmanship is at the World Heritage site of Byōdō-in, in Uji, Kyoto Prefecture. The Amida Nyorai that is enshrined at the Phoenix Hall was completed in 1053 by Jocho, who applied to it a “wooden mosaic” technique (yosegi-zukuri). The Phoenix Hall is one of Japan’s most important cultural assets is not simply because of the Amida Nyorai. Both the Buddha and the Phoenix Hall date back to the Fujiwara Regency Period, the latter being the only example of buildings from that era. The Fujiwaras, famously, were an aristocratic clan that wielded immense power and influence at the imperial court. They strategically intermarried with generation after generation of emperors and princes, dominating Japanese politics from 794–1160 and even puppeteering the throne in the 10th and 11th centuries.

In the next post with Yujiro Seki, we will turn to the august Fujiwaras, and their courtly rivals in the nobility and emerging Shogunate. The fortunes of the busshis under the Inpa, Enpa, and Keiha studios was intimately intertwined with Noble House Fujiwara, and competing tastes in making sacred sculpture reflected the tug-of-war between the old school kuge of Old Japan, and the new military order of the martial shoguns.

Carving the Divine is now crowdfunding for distribution on IndieGoGo

See more

Jōchōyo: One Thousand Years of Impeccable Style

Insatiable Spirit of Inquiry for Virtue and Beauty – Supreme Treasures of Byodoin Temple

Related blog posts from BDG

The Yuji Experience: A Singular Voice for Japanese Buddhist Sculpture